Legend

Cursed

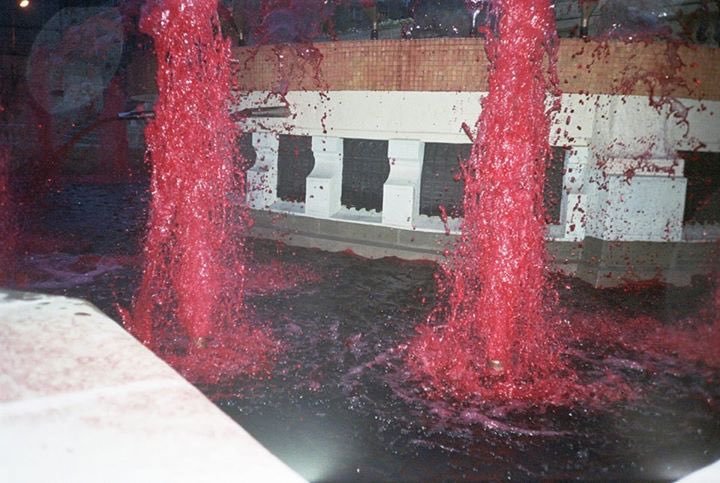

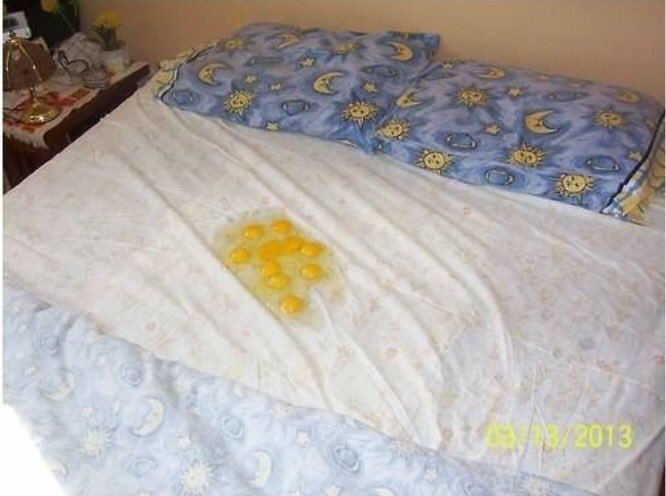

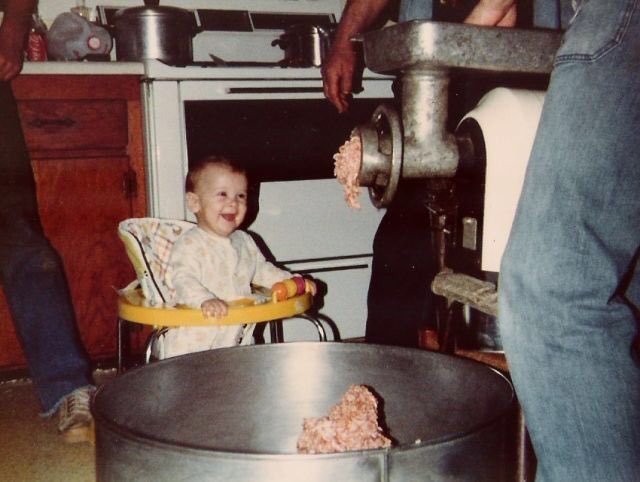

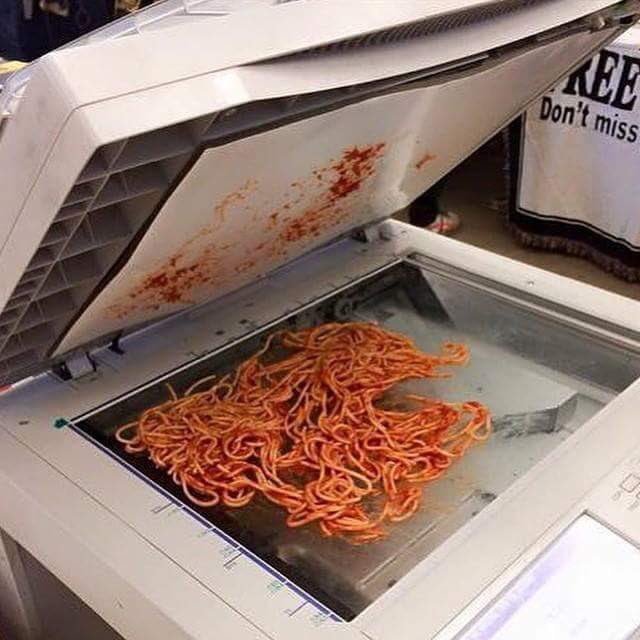

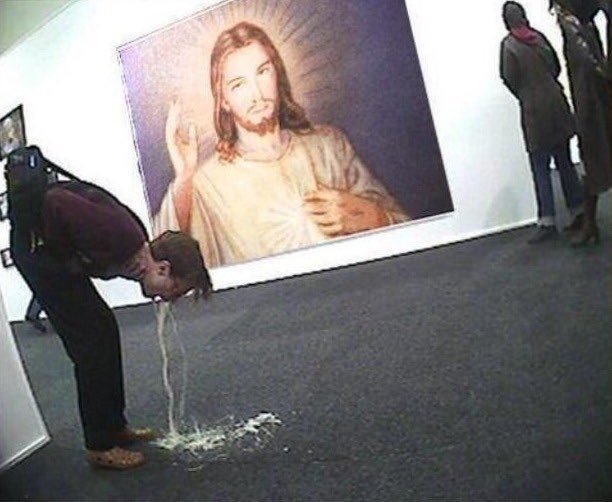

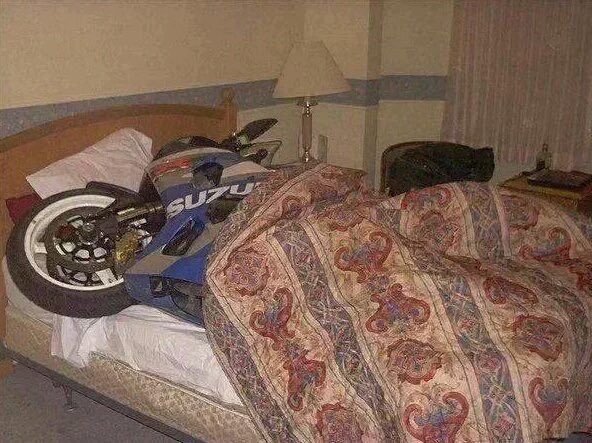

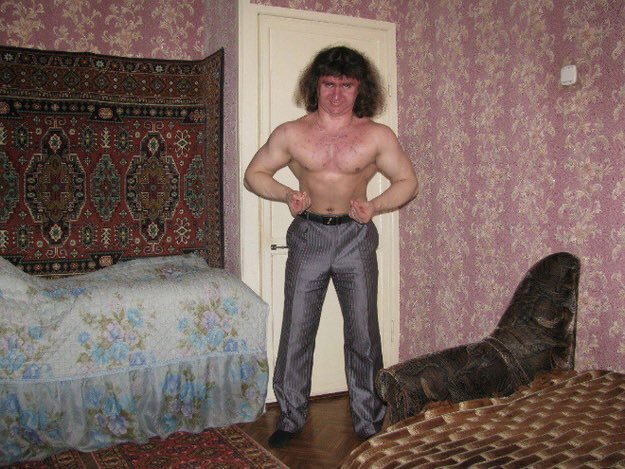

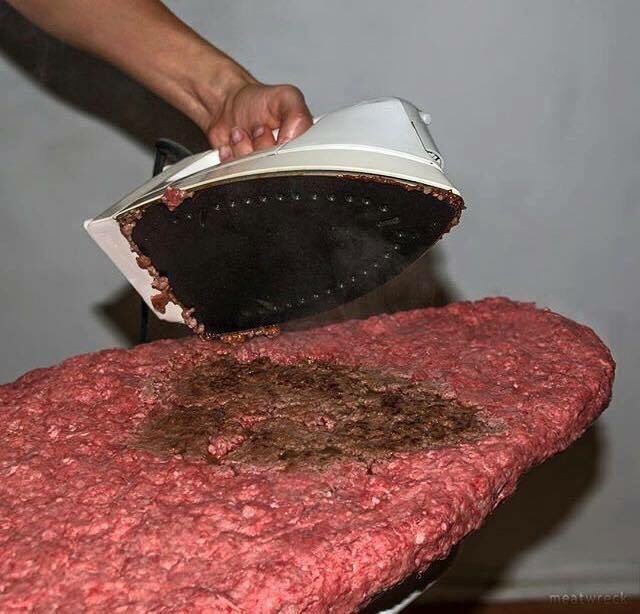

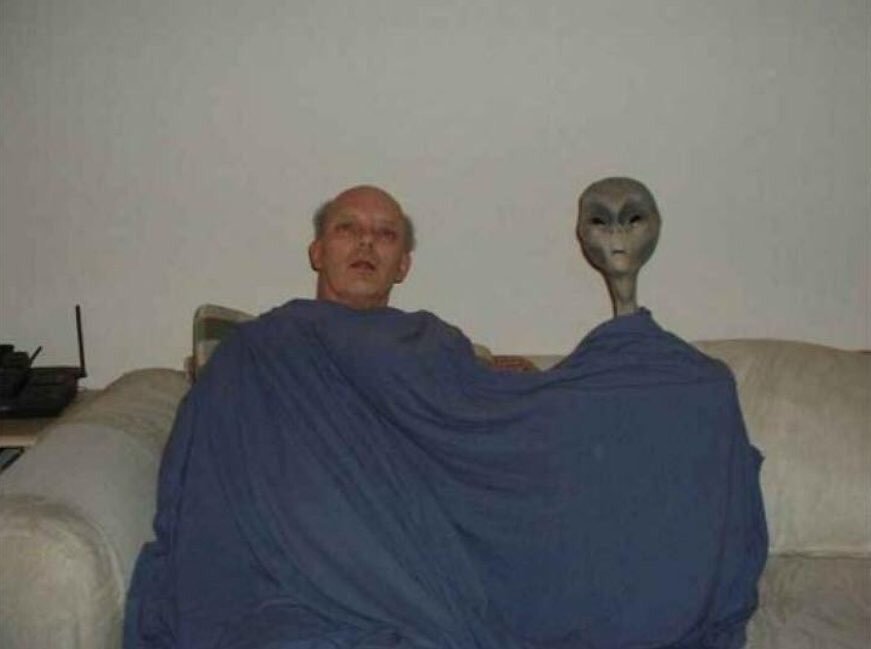

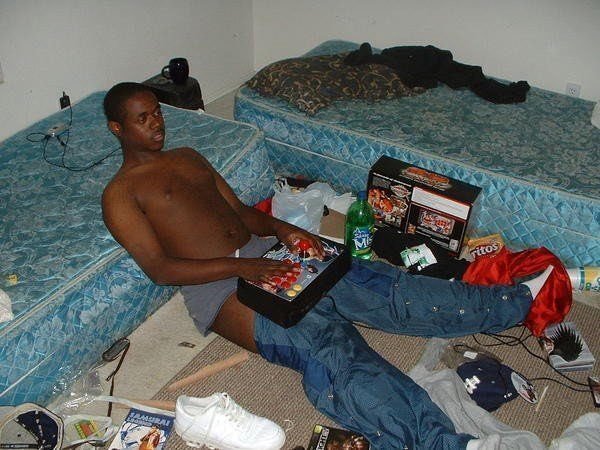

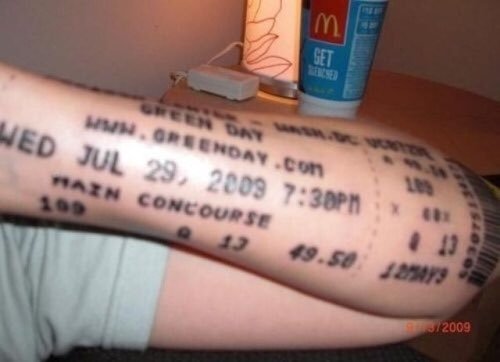

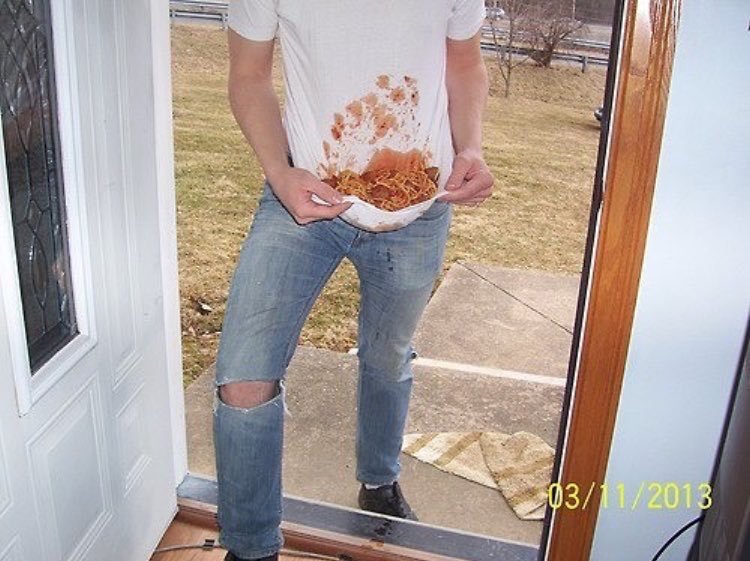

In July 2016, someone registered a Twitter account called cursed images (@cursedimages) and started posting images with a simple caption: the phrase “cursed image” + a number, as if referencing some larger database, though the more you scroll through these, the clearer it becomes these numbers are as random as the bizarre scenes the images depict.

The images are generally lo-fi, often watermarked with timestamps from years past, but not far enough back to be considered retro or vintage. The images come from and often explicitly represent scenes from the early digital era—a hand emerging from beneath the divider of a bathroom stall to recover a dropped phone (image 19823); a row of teenage boys at a LAN party, absorbed in their inexplicably blank screens (47263); a man in board shorts reclining on a disconnected and dilapidated flatbed that he has converted into his bed, complete with rotating fan and a mounted TV playing anime (6)—but the element that unifies these photos is an abject improbability. These scenes shouldn’t exist, but they do, hence “cursed.” Curses are the consequence of trespass, people entering places they don’t belong, whether physical places like burial grounds or more conceptual transgressions like playing god or making a deal with the devil.

Who is this devil? The story behind a curse is usually occulted in some exciting way—skeletons in a closet or buried in a too-shallow grave—but part of the horror of these cursed images is how arbitrary they are, how inexplicable. It’s almost impossible to guess how or why they exist, and the anonymity of the account’s admin only seems to underscore this point. We can’t understand these images, but their origins are also stupefyingly obvious; their grotesque multiplicity could only be the product of late capital, imbuing them with the dread of inevitability. Capitalism promises us choice among a dizzying carousel of options, but this alleged blessing belies the many curses that make this choice possible: subjugation, exploitation, glut, waste. The cursed image makes us confront both sides of the coin at the same time, but doesn’t judge, allowing disgust and novelty and any other reaction we might have to blend into a new kind of affect, this endless gray slurry oozing down our feed.

When will it end? The account stopped posting images a few months after its founding, but “cursed” has seeped into the cultural consciousness, inspiring sibling accounts for cursed videos, tiktoks, and increasingly niche derivatives of the original image account, spawning marginalia like Cursed Conspiraboomer Images and Cursed Images of SpongeBob SquarePants that are as amusing as they are pointless. There are podcasts and thinkpieces dedicated to making sense of the cursed and when a first take isn’t enough, a critic can always rehash and extend their work. Your mom says cursed now. Your boss too. Cursed is itself cursed, a precession of simulacra sprawling in every direction imaginable.

One such path leads here, to this, our thirteenth issue of Territory. We’d like to say our contribution to the cursed discourse offers something new, but all we can offer is our particular map of the phenomenon. It’s an inherently flawed object, but that doesn’t mean it’s useless—far from it.

The cursed image is instructional in this regard, how it manages to transform discarded images of discarded objects into something effecting and fascinating. It’s a reminder that meaning is not an intrinsic property to be mined from an object with the right signifier, but a fluid, reciprocal process of making and interpreting these maps, and that we have an active role in this process. Faced with the many futilities and fallacies of our world, how do we respond? A curse is, famously, also a blessing, and this issue of Territory, if not the larger project, wants to see how an object might also be its opposite. How every phenomenon or object permits a manyness, so long as we encounter it with openness.

The cursed image is instructional in this regard, how it manages to transform discarded images of discarded objects into something effecting and fascinating. It’s a reminder that meaning is not an intrinsic property to be mined from an object with the right signifier, but a fluid, reciprocal process of making and interpreting these maps, and that we have an active role in this process. Faced with the many futilities and fallacies of our world, how do we respond? A curse is, famously, also a blessing, and this issue of Territory, if not the larger project, wants to see how an object might also be its opposite. How every phenomenon or object permits a manyness, so long as we encounter it with openness.

It’s difficult not to fall back on old myths, but it’s worth it, we think. This is no more apparent than when we survey the work of our contributors, work whose complexity and consideration resist easy placement in the feed. Ava Hofmann’s visual poetry is truly sui generis, a collage of language and image equally indebted to the Medieval treatise as it is to a flowchart in a Powerpoint. C Samuel Rees’ excerpts from Bomb Pulse literally drift and mutate as they fallout from the blast that opens the piece. These are pieces that could only exist in this cursed time and in this cursed medium. They demand attention, maybe even a new kind of attention, but reward in kind.

This issue explores more classical curses, too, though this sense of the tradition is always turned on its head. Ray Levy’s “The Use of Pleasure” conjures the French libertines and décadents and a mysterious deer to skewer contemporary academia. David LeGault’s, “A Conjuring” traces the history of the Golem against the writer’s own isolation in today’s Prague. During nighttime jogs, he turns down streets he’s never seen before, which inevitably lead to surprises from the city’s past. Curses, though so often triggered by trespasses of the spatial, always produce temporal disturbances. See, for example, Jessica Alexander’s “You Are Here,” in which we begin with the ordinary curse of an Ohio winter and end with the very real fear that not one word in the title can ever be true. Curses invoke deep histories that stop the future from running too far ahead of the past. Even the most overtly “now” of the pieces, Kelly Schirmann’s “Fire Season,” is influenced by the galactic time of the zodiac, Leo season hovering above the smoke that pollutes Missoula. It casts a rightness over the wrongness, the promise of a system to help us manage the chaos, all while introducing its own entropy. Are there twelve signs or thirteen? Is thirteen a lucky number or an unlucky one?

Cursed is our thirteenth issue and it will be our final one too. The end is bittersweet, but it’s more complicated than that. It’s certainly been a privilege to develop and champion the work of writers we admire. It’s been a grind too, though admitting that shouldn’t tarnish the joy and achievement we’ve felt. The truth is, we’re not exactly sure what we should feel or say. It’s tempting to try to step back and make some larger sense of what we’ve produced, but this feels dishonest for a project built on negation. Perhaps this is what makes Territory what it is, a certain attitude towards futility, a serious but playful impulse to turn things inside out, even if that only makes a bigger mess. Like any other map, Territory was always going to fail, but we’d like to think we failed in strange, exciting ways. The map is not the territory, but it’s all we have, so what do we want to make of it? By now you should know our schtick. After six years and thirteen issues and a hundred or so pieces published, we’re saying the only thing we can think to say.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Jessica Alexander’s “You Are Here” spurs from a visitor’s map of Ghost Town Village, an abandoned amusement park that sits atop Buck Mountain in Western North Carolina. Ghost Town Village, née Ghost Town in the Sky, was conceived as a wild west amusement park; the decision to place it atop a mountain, so that it became the “mile-high park,” was made by a man named Alaska Pressley. While there’s a lot that’s unsavory about a wild west-themed amusement park, the park’s eastern location and its 1,030 meter funicular, modeled after an Alpine counterpart, provide something pleasurably anachronistic or capricious to the abandoned park, just as there is something pleasurable about watching spaghetti westerns filmed in the Spanish and Italian countrysides. You’ll find that same destabilization in Alexander’s story. We begin with the assuredness of its title—”You Are Here”—but the matter of where you are, and who you are, becomes more difficult to divine as the story progresses. Time and space aren’t so easily solved, and you can’t just point to a spot on a map.

Jessica Alexander’s “You Are Here” spurs from a visitor’s map of Ghost Town Village, an abandoned amusement park that sits atop Buck Mountain in Western North Carolina. Ghost Town Village, née Ghost Town in the Sky, was conceived as a wild west amusement park; the decision to place it atop a mountain, so that it became the “mile-high park,” was made by a man named Alaska Pressley. While there’s a lot that’s unsavory about a wild west-themed amusement park, the park’s eastern location and its 1,030 meter funicular, modeled after an Alpine counterpart, provide something pleasurably anachronistic or capricious to the abandoned park, just as there is something pleasurable about watching spaghetti westerns filmed in the Spanish and Italian countrysides. You’ll find that same destabilization in Alexander’s story. We begin with the assuredness of its title—”You Are Here”—but the matter of where you are, and who you are, becomes more difficult to divine as the story progresses. Time and space aren’t so easily solved, and you can’t just point to a spot on a map.

Brian Blanchfield’s “Abasement” is a formal experiment in causality, each sentence addressing the question of the previous only to introduce one of its own. Brian first introduced us to this generative device in the context of his admiration for Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, how the book begins with its narrator knowing next to nothing, allowing the narrative to propel itself through a process of continual discovery. I may be mistaken about this, but I’m currently writing under another of Brian’s constraints, and even if I weren’t, there is no record to consult. Our conversation occurred at Black Crown Coffee in Tucson, a gathering place for all kinds of desert rats. Among the more memorable characters was Richard, a sometimes electrician who could trap you at your table for hours while he rattled off stories about haunted mines in Prescott, being surveilled by the government, the new mobile game he wanted you to download immediately so you could join the blue team and eradicate the terrorist threat around town. Richard seemed like he was also continually discovering what had happened or what he really believed, one dubious leap or accusation at a time. His stories never followed a causal strand, though this opened him up to surprising callbacks made all the more so by the sense that he too was sharing in the discovery of their coincidence. And just when you’d think to ask about that thing he mentioned a couple minutes back, about the pink dress from the hotel that reappeared by the side of the road, he’d be gone, flitting off to another table or out into the blinding heat to spit at some grand injustice. You’d never make him for a poet, but that’s exactly what he was.

Ava Hofmann’s “HXRXSY” is a hypertreatise on Wife-Physics and other gender phenomena. Above the holy city of Yyyy, lurking behind the lattice of biolife, is the ejecta of the machine-god, some of which seeps into our threespace, producing what is commonly called the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

Figure x.3 (right) shows the anisotropies of CMB as observed by the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite.

Figure x.3 (right) shows the anisotropies of CMB as observed by the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite.

Launched in 2009, the satellite had a number of objectives that fed into the larger Cosmic Vision Programme, prime of which was to “image the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the Cosmic Background Radiation Field over the whole sky.” In 2013, initial analyses were made public that “revealed a number of anomalies that are difficult to explain within the standard model of cosmology.” Our understanding today is that these anomalies could be “statistical flukes,” but could also be the detectable features of a “new physics.” Despite this ambiguity, the Planck satellite was decommissioned as planned, starting in January 2012 and concluding on October 23 2013 at 12:10:27 UTC with a final deactivation command.

Tony Ingrisano’s “Four Small Curses” responds to four of his own mixed-media paintings. Ingrisano shared the following regarding his process: “These four paintings were completed using a cut paper technique that I’d been developing for a while. Using squeeze bottles and brushes I’d paint a series of lines that cross a large sheet of watercolor paper. I then slice the paper into hundreds of delicate, uniform strips on a custom-built rig, one at a time. The strips are realigned at an offset and adhered to a wooden panel, creating a unique surface on which to begin laying out the map. This reconstructed substrate is embedded with its own genetic map of the steps of its creation. Aerial views of land divisions have always fascinated me, and each of these maps is an imagined view of some tract that I may fly over one day. The idea that an entire countryside would be organized by color combination points to some kind of utopia for chroma geeks or a dystopic land of exclusion, à la Dr. Seuss’s Sneetches, take your pick.”

Tony Ingrisano’s “Four Small Curses” responds to four of his own mixed-media paintings. Ingrisano shared the following regarding his process: “These four paintings were completed using a cut paper technique that I’d been developing for a while. Using squeeze bottles and brushes I’d paint a series of lines that cross a large sheet of watercolor paper. I then slice the paper into hundreds of delicate, uniform strips on a custom-built rig, one at a time. The strips are realigned at an offset and adhered to a wooden panel, creating a unique surface on which to begin laying out the map. This reconstructed substrate is embedded with its own genetic map of the steps of its creation. Aerial views of land divisions have always fascinated me, and each of these maps is an imagined view of some tract that I may fly over one day. The idea that an entire countryside would be organized by color combination points to some kind of utopia for chroma geeks or a dystopic land of exclusion, à la Dr. Seuss’s Sneetches, take your pick.”

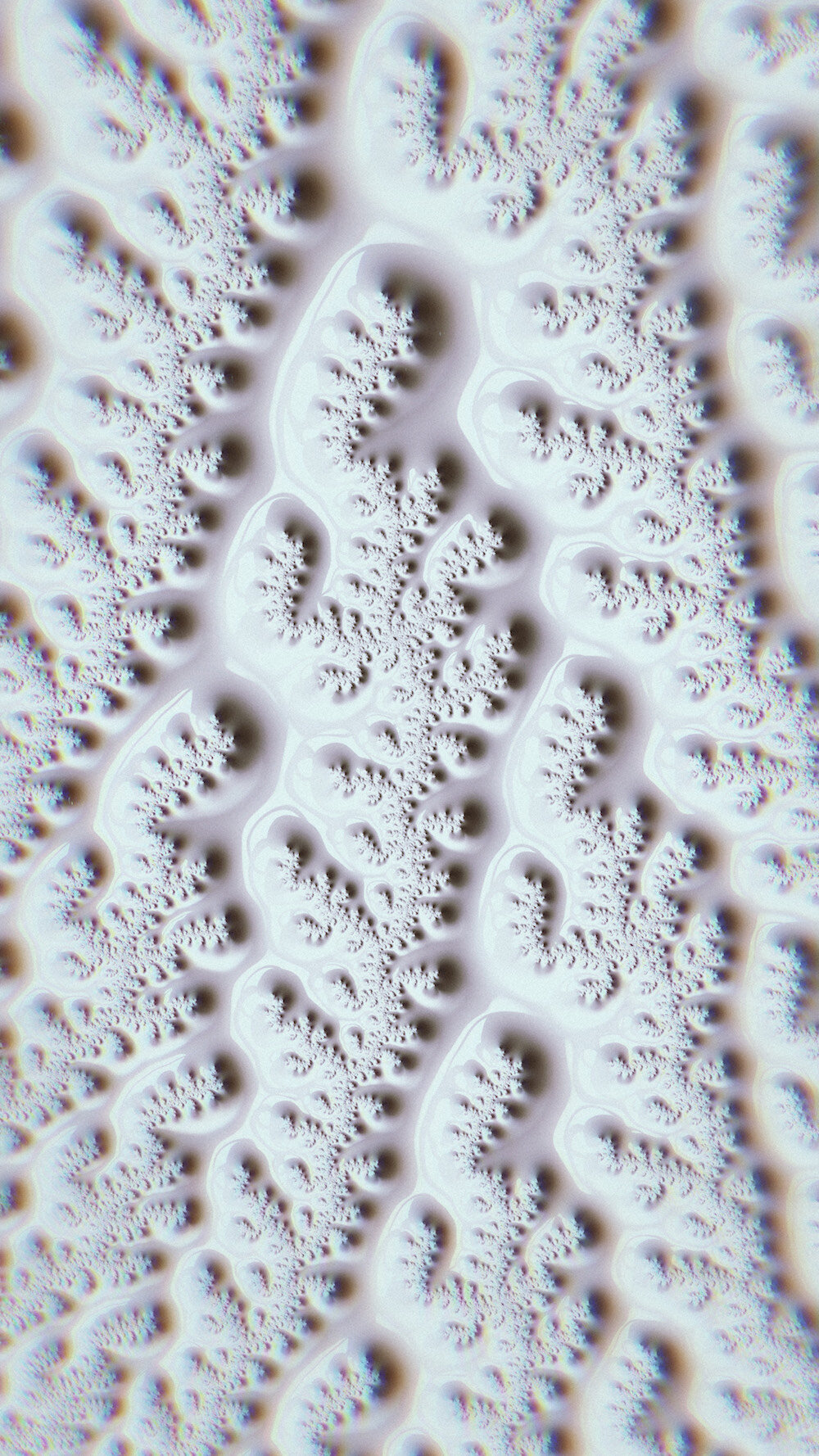

Evan Isoline’s “Mise en Abyme” is, as its title suggests, a cascade of pictures within pictures, though not as explicitly self-similar as the map paired with his piece, a detail of a Mandelbrot set. Benoit Mandelbrot first discovered the set in the late 70s, but it was the success of his 1982 book The Fractal Geometry of Nature that validated fractals as a legitimate mathematical concern and not a curiosity or a program artifact, as it had been accused of being. The book was so successful that fractals crossed over to broader audiences, becoming an avatar of the beauty and mystery of the natural world. Many organisms and other phenomena—ferns, romanesco broccoli, river deltas, etc.—organize around fractal geometries as does human computation throughout the world, systems subordinated by the ubiquity and utility of Euclidean geometry and the formal logic used to explore it. To many, especially psychonauts and other spiritually-liberal thinkers, the fractal’s ubiquity is anything but commonplace. It is proof of a deeper, implicate order to the universe, one that we have unlearned over the course of millennia of civilized living.

Evan Isoline’s “Mise en Abyme” is, as its title suggests, a cascade of pictures within pictures, though not as explicitly self-similar as the map paired with his piece, a detail of a Mandelbrot set. Benoit Mandelbrot first discovered the set in the late 70s, but it was the success of his 1982 book The Fractal Geometry of Nature that validated fractals as a legitimate mathematical concern and not a curiosity or a program artifact, as it had been accused of being. The book was so successful that fractals crossed over to broader audiences, becoming an avatar of the beauty and mystery of the natural world. Many organisms and other phenomena—ferns, romanesco broccoli, river deltas, etc.—organize around fractal geometries as does human computation throughout the world, systems subordinated by the ubiquity and utility of Euclidean geometry and the formal logic used to explore it. To many, especially psychonauts and other spiritually-liberal thinkers, the fractal’s ubiquity is anything but commonplace. It is proof of a deeper, implicate order to the universe, one that we have unlearned over the course of millennia of civilized living.

David LeGault’s “A Conjuring” encompasses the bird’s eye view presented in this 1926 map of Prague. Of some interest, perhaps, are the gentlemen whose portraits frame the map’s title. Dr. Miroslav Tyrš, on the left-hand side of the map, wrote his philosophy thesis on Arthur Schopenhauer and, when he failed to find an academic job, tutored the sons of businessmen. He claimed to have had his cap shot through while fighting as a teenager in the Prague Upheavals of 1848. Jindřich Fügner, on the right, was a German who never felt entirely comfortable speaking Czech. Together, Tyrš and Fügner established Sokol in 1862, a gymnastics organization that lasts to this day. Within that organization, Fügner popularized a new form of second person address, in which members called each other brothers and sisters. Both men suffered unfortunate deaths: Fügner died of blood poisoning at the age of 43 and Tyrš went missing while on vacation in Austria, only to be found thirteen days later in the Ötztaler Ache river.

David LeGault’s “A Conjuring” encompasses the bird’s eye view presented in this 1926 map of Prague. Of some interest, perhaps, are the gentlemen whose portraits frame the map’s title. Dr. Miroslav Tyrš, on the left-hand side of the map, wrote his philosophy thesis on Arthur Schopenhauer and, when he failed to find an academic job, tutored the sons of businessmen. He claimed to have had his cap shot through while fighting as a teenager in the Prague Upheavals of 1848. Jindřich Fügner, on the right, was a German who never felt entirely comfortable speaking Czech. Together, Tyrš and Fügner established Sokol in 1862, a gymnastics organization that lasts to this day. Within that organization, Fügner popularized a new form of second person address, in which members called each other brothers and sisters. Both men suffered unfortunate deaths: Fügner died of blood poisoning at the age of 43 and Tyrš went missing while on vacation in Austria, only to be found thirteen days later in the Ötztaler Ache river.

Ray Levy’s “The Use of Pleasure” is summoned from “The Magical Circle of Solomon,” also known as “The Magical Circle and Triangle,” a diagram found in the 17th-century grimoire The Book of Goetia. In addition to the Magical Circle, Goetia’s summoning ritual involves an elaborate and specific set of tools. A partial list of these required tools: Anointing oil, a brass vessel, the hexagram of Solomon, linen, lion skin, names of God, protective circle, ring of Solomon, scepter, sword. A hoodie, tank top, and pop socket featuring “The Magical Circle” are available for purchase on Amazon, as well as a copy of The Book of Goetia with an introductory essay by Aleister Crowley, a key figure in the Victorian Occult Revival who was known variously as the wickedest man alive, The Great Beast 666, Diogenes, Morpheus, and Super Sinistrum, among countless pseudonyms.

Ray Levy’s “The Use of Pleasure” is summoned from “The Magical Circle of Solomon,” also known as “The Magical Circle and Triangle,” a diagram found in the 17th-century grimoire The Book of Goetia. In addition to the Magical Circle, Goetia’s summoning ritual involves an elaborate and specific set of tools. A partial list of these required tools: Anointing oil, a brass vessel, the hexagram of Solomon, linen, lion skin, names of God, protective circle, ring of Solomon, scepter, sword. A hoodie, tank top, and pop socket featuring “The Magical Circle” are available for purchase on Amazon, as well as a copy of The Book of Goetia with an introductory essay by Aleister Crowley, a key figure in the Victorian Occult Revival who was known variously as the wickedest man alive, The Great Beast 666, Diogenes, Morpheus, and Super Sinistrum, among countless pseudonyms.

Curious about Crowley’s teachings and reputation, one of your dutiful Territory editors attended a Gnostic Mass conducted by a local Thelemic temple, though this is a charitable way to describe a mixed-use rental space between an America’s Value Inn and a hip-hop dance studio. The magicians of the temple were welcoming if a bit oversolicitous, encouraging visitors to help themselves to pamphlets and flyers. The Mass lasted just under two hours and while there was little about the ritual that justified Crowley’s reputation there was some impressive pageantry featuring esoteric vocabulary, important-looking implements, and some extended (female) nudity. During one of these disrobings, I remembered the words of Crowley scholar Israel Regardie, who interpreted Crowley’s The Book of the Law as a “colossal wish fulfillment” to overthrow the strictures of his fundamentalist upbringing. This read cast a perpetual adolescence over the proceedings, which possessed all of that life phase’s sincerity, arrogance, pathos, and horniness, embodied especially in the character known as Heru-Ra-Ha the Crowned and Conquering Child God who is invoked before the Priest parts the Veil, revealing the naked Priestess sitting upon the High Altar. By this point, the metaphors of the lance and the chalice were completely bald, but any creepiness when “the Priest join[ed] hands upon the breast of the Priestess” was dispelled by how kindly everyone was, the men with their graying ponytails and the women serving vegan gumbo afterwards. There was more than enough to take home, but I couldn’t bring myself to take any more.

Analeah Loschiavo’s “The Persistence of Stone” is a first-person account of the narrator’s visit to the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, the location of a pre-Columbian city in what is now southwestern Illinois. Looking at a map of the site, the narrator in Loschiavo’s story “[considers] the myth of the map.” “In the myth,” Loschiavo writes, “the land is abstracted, evacuated of life. These mannequins form a map, and I another.”

Analeah Loschiavo’s “The Persistence of Stone” is a first-person account of the narrator’s visit to the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, the location of a pre-Columbian city in what is now southwestern Illinois. Looking at a map of the site, the narrator in Loschiavo’s story “[considers] the myth of the map.” “In the myth,” Loschiavo writes, “the land is abstracted, evacuated of life. These mannequins form a map, and I another.”

In order to maximize children’s learning experience while visiting the Cahokia Mounds, the State Historic Site’s website advocates they learn the following words: Artifact, Archaeology, Borrow Pit, Ceremonies, Conical, Equinox, Flintknapping, Mississipians, Mound, Pottery, Solstice, Stockade. It is unclear whether the website wants these to register as myth, map, or both.

Madison McCartha’s excerpt from THE CRYPTODRONE SEQUENCE is an exploration of the technocratic gaze, how the modern panopticon can “index / every person place or sniff / you ever loved.” Though this gaze is seemingly omnipresent, it is its most imperious from above, looking down on people not as people, but as targets, identified as such by a network of processes and data too complex for human perception.

The video running behind Madison’s piece is footage of the protests in Baltimore in response to the death of Freddie Gray, as seen from a CESSNA 182T Skylane operated by the FBI. The video is part of a larger tranche of videos released in response to an FOIA request filed by the ACLU that revealed the FBI had been surveilling the protests from April 29 - May 3. According to a declassified memo, the surveillance had been requested by the city of Baltimore, fearing they didn’t have adequate surveillance for the scale of protests scheduled (as indicated by “Social media streaming and intelligence”) and their probability of escalating to looting or violence. The FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG) approved the request and sent one or more Skylanes owned by an FBI front company called NG Research. The plane(s) had been modified two years prior with a Gomolzig Low Noise Silencer System, a Paravion Technology C182-100 Infrared Camera, as well as other cameras and technical infrastructure, which allowed the plane to record detailed footage undetected from high altitudes. This only seemed to have a mitigating effect because the ACLU eventually caught wind of the planes and filed the FOIA.

Freddie Gray died from injuries to his spine. Witnesses said the police “folded” Gray, torquing his legs backwards and pinning him to the ground at his neck, which contradicts the arresting officers’ report that Gray had been detained “without the use of force or incident.” The only footage of the arrest is from one of the witnesses. It shows four police officers hoisting Gray into a police van before cutting out.

Zach Peckham’s “Voided: An Ethnography” essays on the history and ramification of the Quabbin Reservoir, an artificially constructed reservoir in the Swift River Valley of central Massachusetts. An overlay of both the reservoir and the land it flooded is detailed in the map “Proposed Reservoir on the Swift River.” A version of this map can be found in nearby Amherst College’s Special Collections and University Archives. In 1975, the president of Williams, another nearby rival college, alleged that the Amherst library owed the Williams library “at least a million volumes...at reasonable compound rates,” according to the report that the Amherst college library was founded upon books stolen from its rival. Of separate but greater interest, the three photographs that appear in the essay, detailing the layout of Enfield, Massachusetts, pre- and post-flooding, also appear as album art accompanying the band Enfield’s song ‘Sable,’ a “psychedelic, freak folk” track “recorded in Josh’s basement over like a week or so.” Check out their Bandcamp here.

Zach Peckham’s “Voided: An Ethnography” essays on the history and ramification of the Quabbin Reservoir, an artificially constructed reservoir in the Swift River Valley of central Massachusetts. An overlay of both the reservoir and the land it flooded is detailed in the map “Proposed Reservoir on the Swift River.” A version of this map can be found in nearby Amherst College’s Special Collections and University Archives. In 1975, the president of Williams, another nearby rival college, alleged that the Amherst library owed the Williams library “at least a million volumes...at reasonable compound rates,” according to the report that the Amherst college library was founded upon books stolen from its rival. Of separate but greater interest, the three photographs that appear in the essay, detailing the layout of Enfield, Massachusetts, pre- and post-flooding, also appear as album art accompanying the band Enfield’s song ‘Sable,’ a “psychedelic, freak folk” track “recorded in Josh’s basement over like a week or so.” Check out their Bandcamp here.

C. Samuel Rees’ excerpt from Bomb Pulse connects innumerable texts from the nuclear research and testing conducted at Alamogordo, where his grandfather worked as a military policeman for the Manhattan Project. The piece follows the many fallouts from the project, many of which have been lost to the archive or never made it there at all. For the people living near the Trinity Site or downwind, many of them Mescalero Apache, not only were their accounts of the blast not recorded by project officials, no one warned them about the test, which was infamously three times more powerful than calculated, the explosion going 7.5 miles into the atmosphere and spreading plumes of radioactive ash and other debris throughout the Tularosa Basin.

C. Samuel Rees’ excerpt from Bomb Pulse connects innumerable texts from the nuclear research and testing conducted at Alamogordo, where his grandfather worked as a military policeman for the Manhattan Project. The piece follows the many fallouts from the project, many of which have been lost to the archive or never made it there at all. For the people living near the Trinity Site or downwind, many of them Mescalero Apache, not only were their accounts of the blast not recorded by project officials, no one warned them about the test, which was infamously three times more powerful than calculated, the explosion going 7.5 miles into the atmosphere and spreading plumes of radioactive ash and other debris throughout the Tularosa Basin.

The decision to detonate the bomb without informing locals was a calculated decision by the project leaders, not wanting to tip their hand in anticipation of the planned bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Of course that doesn’t explain why afterwards, there were no clean up or safe water initiatives, and how, only recently Trinity downwinders are being acknowledged, most visibly by their inclusion in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, originally only for the victims of the Nevada Test Site. The act has been amended multiple times, each time expanding to include groups and conditions the previous iteration had missed, including a 2002 amendment to add back a downwinder area that had been accidentally removed in a previous amendment.

Kelly Schirmann’s “Fire Season” maps an afternoon walk with a friend along the Clark Fork River in Missoula. What might be an easy stroll is polluted literally and figuratively, the smoke from wildfires giving all of Western Montana an apocalyptic dread. Though a nearby fire at Mount Sentinel was contributing to the smoke, the “main culprit” was actually the many wildfires in California and Oregon carried north and east, as seen in the darker streaks in the essay’s map, a satellite image produced by spectroradiometers and infrared sensors on NASA’s Terra, Aqua, and Suomi NPP satellites. Somewhere beneath those streaks is Missoula, and Kelly and Sue talking Leo season and home-schooling.

Kelly Schirmann’s “Fire Season” maps an afternoon walk with a friend along the Clark Fork River in Missoula. What might be an easy stroll is polluted literally and figuratively, the smoke from wildfires giving all of Western Montana an apocalyptic dread. Though a nearby fire at Mount Sentinel was contributing to the smoke, the “main culprit” was actually the many wildfires in California and Oregon carried north and east, as seen in the darker streaks in the essay’s map, a satellite image produced by spectroradiometers and infrared sensors on NASA’s Terra, Aqua, and Suomi NPP satellites. Somewhere beneath those streaks is Missoula, and Kelly and Sue talking Leo season and home-schooling.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page or explore other issues.