You’re probably wondering why North Carolina.

It was the last place Joyce Strong went.

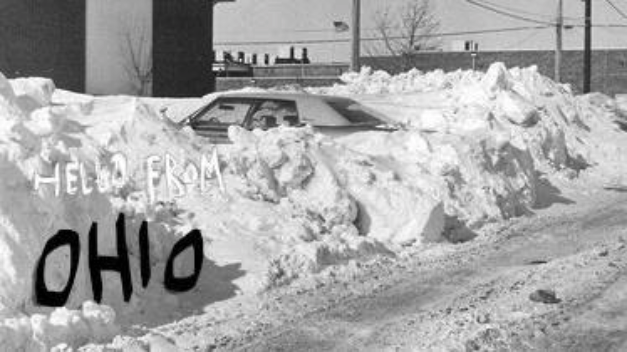

And it was cold in Ohio. I got ear infections every winter. In school we were reading “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” and I had met so many Ancient Mariners. I walked everywhere in a giant winter coat. They rolled up slow, yelled “slut” out their windows or asked where I was going. My ear hurt. I was going to the doctor. She put her deft, cold hand on my back and when she said to take a breath, I gasped. I had not been touched—in what?—a year, and I wished that she would never stop. The sky was always battleship grey, which is to say unbearable, a spiritual heaviness; a shift in the gravitational force. In winter, in Ohio, no one stood up straight anymore; they walked like cursed birds. Besides that, I was sad. I was waiting for a postcard. Every afternoon, I checked the mailbox. For two years, I’d waited for Joyce to write. The box was frozen shut.

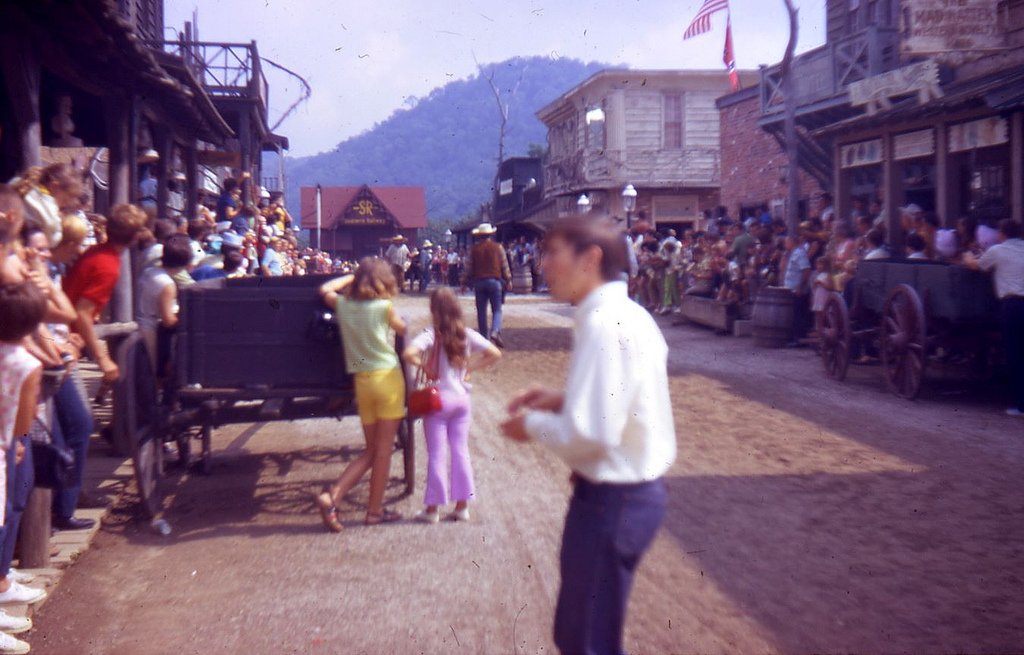

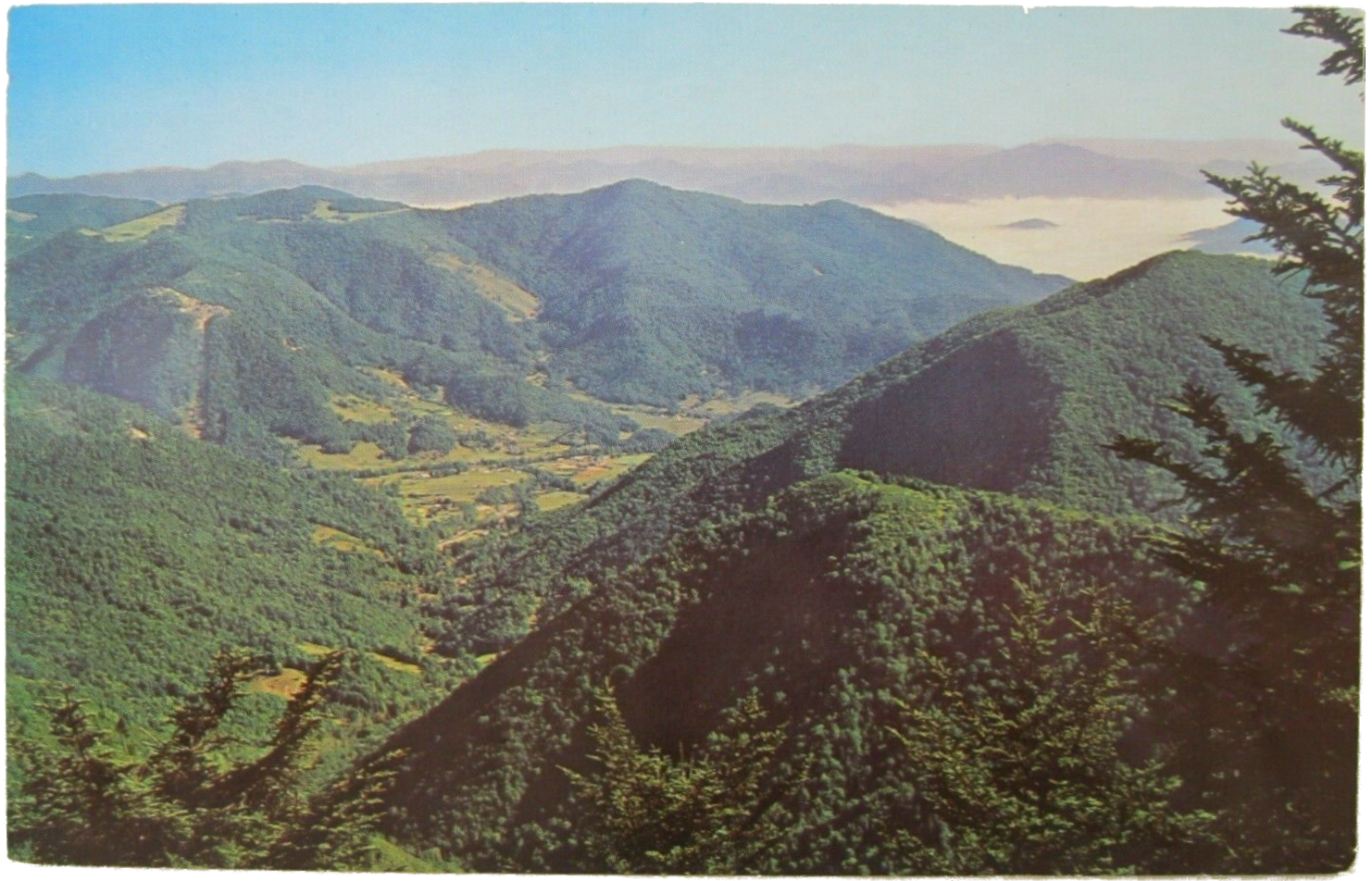

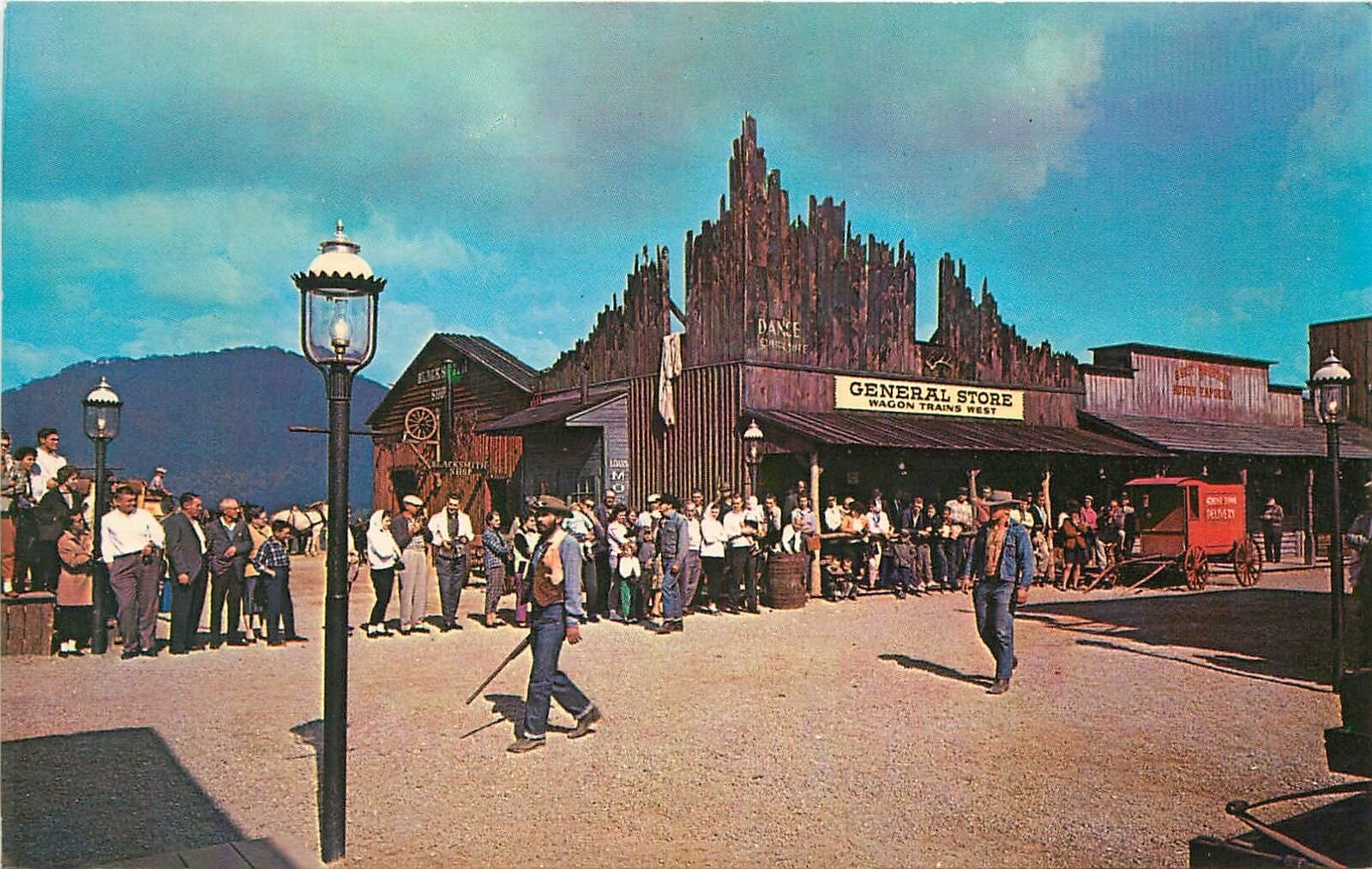

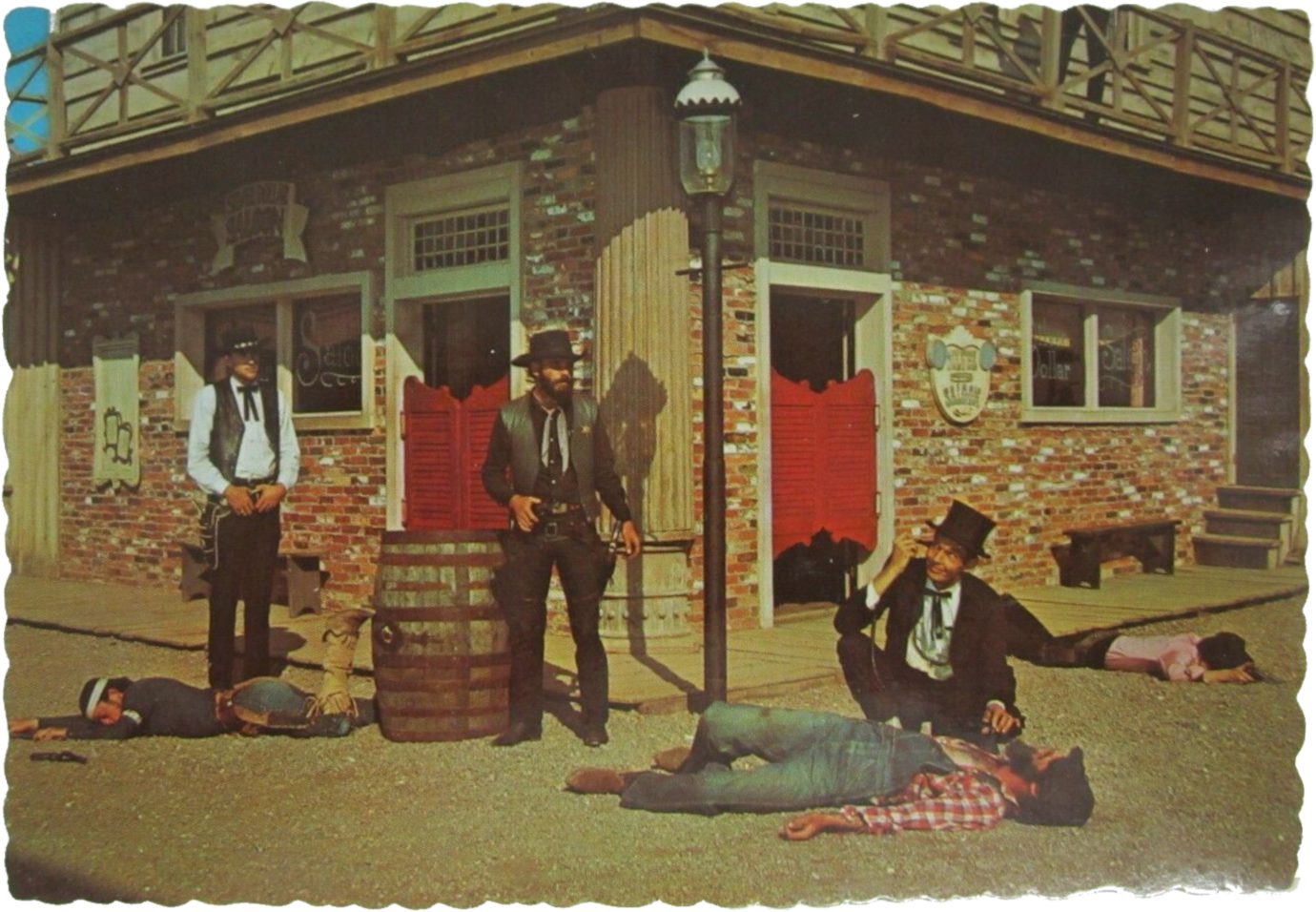

And then just like that, on a Tuesday, the postcard came. It was from Maggie Valley, North Carolina. It looked just like a John Ford film, like a western with the color added in. The sky a faint pink stain and under it a saloon, a bank, an undertaker, a silver nail pegged into a wanted poster. The flat facades and parapets hid the gabled rooftops. Two dusty men stood in the street, holding pistols flush to their hips. One man clutched his gut and crumpled to his knees. It said, “Ghost Town in the Sky;” it said, “Let me help.” It said, “Yours Joyce.” And that was it.

So I went.

I did not expect to stay long. I’d read about Ghost Town. It had once been a wild-west themed amusement park. They hosted live action shows. Gunfights. The guns, of course, were loaded with blanks. Except one day in 1993, when a performer really did get shot. Eventually, he died from it, but first he said it was no accident. That wasn’t the only incident. The place was cursed. A rollercoaster broke in ’94. In ’95 retaining walls gave way and a massive mudslide took out 40 homes at the foot of Ghost Town. Shortly thereafter it shut down for good. It sat abandoned, now, on the top of a mountain.

It only took two days to get there. You could not drive to the top. You had to stop—halfway to the summit—where the welcoming center, a dilapidated shack, sat in a sea of asphalt. The windows were all broken. Ferns burst through the cracks in the parking lot. In the distance, the rusted rails of a rollercoaster rose over the trees and twisted back into the ground. You had to park. You had to take a train to the top. It looked just like everything else. I mean, I was evaporating. I was a cloud and the birds flying out of it. A scratching sound stunned me back into myself. It came from the ticket booth, which looked as if it had been partially absorbed by the mountain; thick foliage sprouted over the rooftop. It could be dead leaves. Rats, maybe. Somehow I sensed it was something else. The sensation was magnetic! It tugged me to the entrance and I kicked the door in. It seemed so easy. A scene unraveling outside me. The way a miracle happens so quickly—in an instant the world comes unbound—and then wraps itself up again.

“Joyce,” I said.

She faced a cracked window. She stood with her shoulders thrust back. The merchandise—t-shirts, shot glasses, key chains—had been picked over. The floor was littered with dead leaves and postcards. Someone had thrown the cash register through a display case. It was upturned—and I could almost see it falling in a shower of sparkling glass. Joyce turned and her smile was sort of startled and pleased. She tucked her hair behind one ear. It occurred to me then, that I’d never imagined her ears. They were flat and big. I loved them.

“What socks are you wearing?” she asked.

I pulled the leg of my trouser up.

“White, athletic socks,” she smiled. “That’s just how I pictured it.”

Here’s what I forget. That the world is not undone by a miracle but in the process of undoing itself. It takes hard work to sustain it.

What I mean is: there’s nothing I could do to keep her. I knew this. Because I took a minute to catch up, I had to twist myself inside out to be in step with the miraculous. I backed up, took a running start, and by the time I’d sprung fully into our encounter she’d already gone.

This always happens.

Why should it matter? It mattered immensely to me. Let me explain.

I had been a student. That’s how I fashioned myself and it was helpful. My mind and my days were curated for me. My classmates were busy trying new things, like cocktails and gardening. Meanwhile, I was on the library’s tenth floor studying Balthus prints, wondering why, why, why these cats? I know it was the wrong question. But my point is, everyone around me seemed born with an instinct for living. It was a gift, I guess, both vital and basic, and I didn’t have it.

Instead, I had a nemesis. His name was Craig.

In Art History class, we’d pin prints to the walls. This was in August. There was Cat with a Mirror. The cat looked like a puppet, perverse, maybe demonic. It looked like it just sprung up into the bedroom of a young girl. The girl was unphased. She held a mirror to the cat’s face; the gesture seemed to please them both, I think. A teacher of mine once said: school is a garden. Some plants flourish and some don’t. This, too, was an education. An arrangement. A garden. You pick something—the options are limited—and you take it apart. I picked Balthus. “Who brought this?” Craig said. I did. Back then, I was learning that the rules people care about are never spoken. You say what you shouldn’t and it’s like crossing into the negative of a photograph. Craig looked at me like I’d brought a juice box to a potluck. “Why?” He asked. And I hated him because I did not know myself. That’s when I saw the painting and I thought I’d faint. Oil on canvas. A drowning girl, I think. The artist’s name was Joyce Strong.

Craig brought the painting. “Craig,” I said, “you’re fucking with me.” He was telling Irene about a hand job he got in a Kusama installation. She was smiling. I said, “That’s me.” His eyes shifted to my face and his shoulders stiffened. The painting was called Knot, which is my name: Robin Knot. I learned that strong emotions and their expression have this effect: people like Craig cringe at it. Of course, the intimacy of an insult, too, is horrifying and invasive. Still, I could not help myself. If he’d admit I did not live alone, vexed only by my own awful shadow, admit we had a common world, that his actions and my reactions weren’t entirely independent, I could clip the thread that linked us and be forever free of him.

He didn’t. And just like that our fates were sealed. I was destined to hate him.

“Robin,” he said, “that’s not a person.”

And this was true. It was not exactly human. It had, for instance, no face or body. Nevertheless, it was me. And, naturally, I had to pivot slightly—like someone holding something heavy—I had to set my shame on a surface equipped to support it.

Joyce Strong was the name of the artist. Craig saw the painting in 2004 at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. “I’m writing my thesis on her,” Craig said. I was livid. Manet was Craig’s favorite impressionist. His greatest joke was to turn a goddess to a “floozy.” His word, not mine. And it makes you want to cry. How dull and unimaginative the whole game is: a fistful of dickheads just flipping the same coin over and over again.

I said, “I’m also writing my thesis on Joyce Strong.” I’d decided right there and then. Craig’s mouth hung open. He said, “Two minutes ago, you didn’t even know she existed.” I wondered whether I should kill him. Should I kill him? I thought.

Instead, I wrote Joyce Strong.

I saw your painting: Knot. It looks like you threw a handful of sand at me. That is, if I were invisible. Let me try again. When I was young, I walked barefoot, everywhere. Once, my mother took a pumice stone to the pads of my calloused feet. At first, it was wonderful to feel everything: the soft rug, cold tiles, blades of grass bending into wet earth. I went further out and the rough boards, the rocks, and pine needles cut me. I’ve been thinking of this, it is a portrait—though Craig says it isn’t. I don’t believe him. If a body were tactile, I mean—I felt like I had been caressed. At first it was pleasant and now it’s agonizing. Until I saw Knot I identified only with cats in Balthus paintings. I’m strange, I guess, and possibly stupid. I know you painted me. I’ve never been so sure of anything, pertaining to myself, at least. I also believe the experience is ruining me. I said, We’ve never met. So, how did you do it? And can we? Can we meet? Yours, Robin Knot.

I sent the postcard and I went to the library. I was done with Balthus. I needed to learn, immediately, everything I could about Joyce Strong. There was almost nothing biographical. It didn’t matter. I’d always moved toward biography wincingly. So sure it would disappoint me. Joyce Strong lives in Vermont with her husband and four children. You know that sort of thing. She’d be someone, I feared, who lived so legibly, she could not teach me anything. There were no photographs of her. That was also just as well. I wanted only her paintings inside of me. I was thinking all this, my pen poised in the air, when Craig sat down across from me.

“What are you writing?” he said.

Was he following me? I covered my postcard with my arm.

“Nothing,” I answered.

He told me he’d been watching Joyce Strong interviews all afternoon. “Ever play Stone Face?” He asked. “It’s a game. I learned it in eighth grade. Let’s be honest, I still play. It goes like this: there’s a desk, and under it someone’s hand is undoing my belt, unzipping my pants, and, obviously, I’m doing the same thing to the other player. Above the desk we sit, attentive, bored even, chewing our pen caps. The first to break, you know, loses the game. There’s an interview with Joyce on YouTube. This guy, a real Charlie Rose, sits across the table from her. His tie is loose, he looks tired, a little listless, unimpressed. It’s some real Abramovic shit, the intensity of it. They’re like really looking at each other. He’s saying, ‘Talk about landscape. Talk about technology. Talk about the body. Is that so? How so? Expand on that? Give me an example?’ And, of course, I’m thinking: where are their hands? Not on the table. Then something happens: in the last thirty seconds of the video, he fumbles, his mouth falls open, and—”

I stood. I slammed my book shut. “You’re lying!” I shouted.

I stormed toward the elevator doors. I jammed my finger into all the buttons. There were two. The single elevator stalled on the seventh floor as if it was confused. I was thinking: Joyce Strong has ruined me! I took the stairs instead, sat down in the empty stairwell. I started writing:

Joyce, you’re probably wondering what I mean. You ruined me. I will tell you. I have looked up your work. I have looked up all of it. I have not seen your photograph; there’s no biography. But I imagine your eyes would be a cool grey if they were not already black and your gaze is a dog’s gaze. It is very still. It asks nothing or everything, which is, maybe, the same thing. Your smile is sly, I think, and pleased. There is a man sitting across from you—his name is Craig. This is an interview. His relationship to his haircut and mustache is best described as ironic. And his eyelids will flutter as he tells you this. Still, he will stutter when you smile at him and lose the thread. Are you mocking him? I cannot tell. Maybe you are not. Maybe your smile is warm because you know he is not brave enough to have imagination. And you watched and you discovered this and you are finding a way to love him even if he phrases his questions as imperatives, and his vocabulary is abstract and bloodless. You are so competently opaque. He has that practiced look of listlessness, of being unimpressed, those anemic, erudite, and surly eyes. That’s when your smile startles him.

In Ohio there is one main drag, and the railroad cuts through town. I covered my ears in headphones. I walked. Often it was cold. Always cold. I’d discovered this electronic music: retrofuturism. Spectral sound. Like layers of time co-existing. One night, I stepped out of the soundscape and I slammed into Craig. Sometimes, when I looked at him, I tried to see what someone else would see. Maybe Irene. What did she see? Was he good looking? He held a stack of books, and when I rounded into him, they scattered across the sidewalk. Allen Jones’ autobiography was splayed facedown. Really? Some postcards had been wedged between the pages. I picked them up: New York, North Carolina. He’d been to New York last weekend. “Joyce had a couple paintings at the Hudson Gardens show,” he said. “I thought you’d have known.” I hadn’t. “I thought you’d have gone.”

“Yea,” I said, “I saw them.” I was lying.

“You’re probably wondering why North Carolina,” he laughed.

I wasn’t. “Craig,” I said, “you’re not really a feminist.” I handed him the book on Allen Jones. “I just thought someone should tell you that.”

That night I dreamt I took a greyhound to New York. I wanted to sit above ground and see my faint reflection in the glass and the changing landscape underneath it. The next morning, I wrote Joyce again:

Joyce, I went to see your paintings at Hudson View Gardens. I took a greyhound. I got off. I went. You were not there. Why did I imagine you might be? Eventually, I took the greyhound back again, but first I walked around. Most of the work looked like Hoffman and Rothko knock-offs and I did not care about them. I walked on. Your painting was a gash in the sky. I knew it was you before I read the name and I stopped breathing. Acrylic and pen. Pen? I don’t understand. I stopped. My heart fell through the floorboards. Did you feel it? The painting looked just like a blood clot floating under water or across the clouds. I stopped. I met you in that bloody landscape full of stained cotton balls and I grieved for fear I’d never find you anywhere else. Did you feel it? Of course not. How could you? That’s when I saw Craig, leaving the gallery. I don’t think he saw me. I covered my face all the way into the street and I held you in my mind. I said, Joyce, what did you mean by it? Two gashes in a canvas like eyes swollen shut or a sunset beaten red. Craig was stupid and wrong. They were obviously faces! Faces and landscapes. Did you feel it, too? Of course. Somewhere else beneath an awning, up the block, you sipped your drink and felt it, too. Only, I couldn’t imagine exactly what you were drinking and this grieved me. I rushed out of the gallery into the street. Outside, was gritty and a taxi nearly knocked me down. I felt so out of step with time. Outside the gallery, Craig leaned against the brick façade and lit a cigarette. He said, “Smile, Robin. It can’t be that bad.” And I told myself, it is. It is that bad. I held you in my mind all the way back to the bus station and, of course, I knew you were not really there. So what the fuck was I holding?

Time is a strange thing. Suddenly it was spring. Craig was writing a thesis on Joyce. I was pretty much flunking out, skipping class, listening to spectral sound and wandering around. It was a shitty town. There was a coffee shop called Grounds for Talk. There was a bar called Angry Charlie’s. There was a pizza parlor with a tip jar that said, “Show me your tips.” There was an image of a topless woman taped to it. When it was cold—and it was always cold—the streetlights flashed against the snow. I stepped out from behind a building and the wind nearly knocked me down. In spring, the students drank on their porches all day. Twice they threw a beer can at my head. I was riding my bike so slow it nearly flopped over. “Get a car you stupid cunt!” They shouted. I’d never before been exposed to a population whose anger was so totally arbitrary. Joyce did not write me. It didn’t matter. I went to bed and in the morning I woke up again. This kept happening. I kept writing. It was a ritual. By that I mean ceremonial. An exorcism. My ardent commitment to walking nowhere, listening only to spectral sound, skipping class, and writing postcards, would, I believed, inevitably unveil the agent of my undoing. I was thinking this, recommitting to my practice, when the first postcard arrived:

There is too much I want to know. For instance, what socks are you wearing? Do they match? Do you care? What was it like for you to live a girl’s life? Did you like it? Did you wish for something different? Until very recently, you did not know of me. Now you do. Do you think that changes everything? Have you been vaguely waiting for something to change everything? Robin; I like your name. I want to say it slowly so you feel it. I wish you could hear me say your name slowly, again and again. If you were here with me, under a striped awning, drinking chenin blanc, I would begin and end every sentence with it, Robin. Robin, are you sitting in a stairwell? Is there a rug on your floor? Do you vacuum the rug? Is there a pile of books on the corner of your desk and when they topple over do you pick them up? Do you lay on your back and look at the ceiling? Are you listening for a sound outside your door? Or to a song? What song? Robin, are you sitting in a chair? Is there a book open on the table? Are you staring out the window, Robin? What are you thinking? Do you think of things that happened long ago and wince in shame as if they are still happening? They are still happening, you know. Do you think you are immortal? Do you wear your seatbelt? Will you wear your seatbelt? Do you eat cereal for several meals? Somehow, I have always known you do. What causes you to feel contempt and is it obvious or do you take great pains to hide it? If I put the entirety of your ear inside my mouth, would you like it? What would you ask me to do after that? And after that? And after that? And now? Will you tell me what to do now?

Spring passed. Craig spent the summer at my table on the tenth floor. He was writing his thesis. In the fall, he would successfully defend it. The library was, otherwise, pretty empty. He said Joyce’s landscapes were recumbent phalluses, not faces. I took a leave of absence. It wasn’t enough. I needed him to shut entirely up, I was thinking, as I opened my mailbox and found another postcard.

Robin, I am sitting in a room. I am wearing an A-line skirt with a waistband that’s elastic. Across from me sits your friend with the ironic mustache—Craig? He tells me my work is about the phallic technology of landscape. He uses the word “dichotomy.” Tell me, he says, about this dichotomy. There is a table between us. He rests his folded hands on it. You are there. Under the table, on the floor, brushing against me like a cat. You press your head into my calf. You press your head into the inside of my knee. You rest your head in the hinge of my thigh. Craig can not see you. You tug my skirt below my hip. You are trying to fit the entirety of my hip inside your mouth. And I smile—and my smile confuses him, because he knows it has nothing to do with his questions, and yet, he thinks, there’s no one else here.

So, I gloated. I went to the library’s tenth floor, where Craig hammered—like a toddler—on his keyboard. I waved the postcard in his face. “I have been writing Joyce,” I said, “and Joyce has written back!” The library was so quiet, of course. You could hear someone close a book. I loved how the sun dropped—like the blade of a knife—onto the table at 5 o’clock, illuminating all the particles of dust that floated in the golden light. Craig looked up, a little stunned. “Robin,” he said, “you aren’t making sense.”

“I wrote Joyce!” I was flushed, breathless. I’d run all the way from my house, up the steps. “You’re wrong about the interview!”

“That’s highly unlikely,” he said.

I was already composing my next postcard in my head: That man, Craig, is ruining everything. I think I need to kill him, Joyce.

“Joyce died,” Craig said. “She’s dead.”

Nevertheless, I sent the postcard and Joyce wrote back. She said: Let me help.

So, I was saying: a miracle is swift. You don’t want to fuck with it. You just brace yourself like you’re waiting for a hard slap. But the thing is I had so many questions. “Joyce,” I said, “are you dead? Can dead people write postcards? Can you touch me?”

She nodded. “Yes,” she said.

Miraculously, the glass crunched under her boots. She stepped over the scattered postcards, her arm slightly outstretched. I blinked because it was too much. I inhaled, felt my chest rise, closed my eyes, which rolled back. I braced myself: she’d step forward. She’d stretch out her arm. Her wrist bones were like a bird’s bones. Like a pelican or a heron. I thought she must hold things so completely like when people warm their hands on a mug of coffee. Will she hold me, I was wondering. I shuddered and when my eyes, at last, opened, Craig stood there. His hand cupped around my shoulder.

“It’s me,” he said.

What, I wondered, does that even mean?

What’s more I didn’t understand his outfit. He wore a wide brimmed hat, a wild rag, a holster, slung low on his hip, and two pistols.

“I’m Joyce,” he said.

I’d never guessed that this would be one way my heart could break. My long walks, I knew then, had never been an exorcism. I’d arranged my mind like a vast and abandoned castle in want only of a ghost. And she chose Craig.

And just when I’d decided to impale myself on a piece of broken glass, he winked at me. He passed a pistol into my hand, which I tucked into my elastic waistband. He kicked the door open and we stepped into the dusty street where a crowd of tourists were waiting to be entertained.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Jessica Alexander’s story collection, Dear Enemy, was the winning manuscript in the 2016 Subito Prose Contest, as judged by Selah Saterstrom. Her fiction has been published in journals such as Fence, Black Warrior Review, PANK, Denver Quarterly, The Collagist, and DIAGRAM. She lives in Louisiana where she teaches creative writing at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

30.2241° N, 92.0198° W

The roads are poorly paved and sometimes there are palm trees.