I had the right to say nothing at all. I was under arrest. I had trespassed the home we were planning to buy; in fact it was alleged I had broken and entered, and slept overnight in the Littlejohns’ basement. I had been spied, before the inspector arrived, by one of the Littlejohns, a man, perhaps a family uncle, one of several, from the top steps of the wooden staircase down. He must have heard something at ground level. I was stuffing the dryer with the sheets I had slept in. It was step one of the plan I had rapidly formulated, preceding other steps: to fold the cot and stow it where I had found it; to tidy up and hide the pages of my manuscript, which I had been reading before I fell asleep; then, if there really were no exit down there, to ascend the stairs right after eight to join without incident the party wandering the house with the inspector. Once he’d arrive I assumed I could blend in, and explain myself as having gained entry when he did, according to customary arrangement. Customary arrangement was something one could claim when assailed. This is what one does, a buyer such as I and an inspector such as he has hired. It is called a walkthrough.

I had the right to say nothing at all. The policeman with his digital clipboard was himself indication that anything hence would be actionable, if more was said. He had been waiting for me when I descended at last from the loft area, at the very height of the house. I backed down the ladder, feet first. The loft was an unusual space, which couldn’t be exited by door, face forward. Going in, upon hatching, one crept, one learned to crawl. The floor was not reliably weightbearing, slatted with old barrel or bucket staves, and was circular, and the whole room, more or less a bucket, was canted. The floor was to spin, and one’s own weight would set the thing in motion, and pulls or straps along the walls were handholds, assists, and there were portal windows, open, at just the places where, if centrifugal force overcame self-control and balance, one could be pitched out into the sky. It was designed this way, to be a ride, a blur, a near-death amusement. I understood it was the teen Littlejohn’s room. It was like the house, or my crime inhabiting it, was structurally regressive, and to graduate toward violation’s conclusion was to be pulled up through the levels and spat out in adolescence, to gradually require separation from the sociality of adults and removal to one’s hedonist privacy: home. William Maxwell says it somewhere in The Folded Leaf: that the teenager gets so brooding in his sexuality and self-sanctity that all he requires of others is their absence.

I had the right to say nothing at all. It was deceptive, but not illegal, to withhold the entire truth. I represented myself accurately in everything I had thus far signed as buyer. I had been pre-approved for a loan sufficient to purchase the house from the Littlejohns. John and I had been advised by our realtor to go back to our lender and get preapproved as Brian Blanchfield, not Blanchfield and Myers. If we wanted this home, it was smarter not to bid as a couple. The listing agent was a deacon in Christ Church, and the Littlejohns, the sellers, were the most prominent family in Christ Church, which operates New Saint Andrew’s, the Classical Christian college expanding downtown, and which has a history of discrimination against gays, discrimination that cannot be prosecuted. In instances when one of their own bids against an undesirable party, the church is typically able to marshal the resources to enable the buyer to pay cash, which—even if the sum is less than what a gay couple might borrow to pay—is an accepted criterion on which to prefer one buyer to another, and anyway John and I are not a protected class of citizens in Idaho. Federal precedent still maintains that gay, lesbian, and trans people are not covered under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and in twenty-six states, including ours, there is no law on the books to protect our rights not to be denied housing for being who we are.

I had the right to say nothing at all. My arrest was beginning, my apprehension all along coming to term. Everything was seeded from the start, by the givens that preceded us; and our thorough passage, room to room, through reprieve and spite and dread and the gumption that accompanies resignation, were but chapters in the story predestined to conclude this way. The burning fuse on the dynamite was, even more than witness of my presence, the stack of my manuscript beneath the cot. I knew the loose leaf book was proof, when, as our tour moved back upstairs, I watched the trailing Littlejohns discovering its pages, one of them off by himself reading some of each leaf before he dropped it into the dustbin. It amounted to my autobiography. It said who I was. I had needed to write a book that thought through things, that unpacked what was fraught where my life intersected the culture’s, and to do it in a way that consulted no one and that pushed me past compunction, free that way to go for broke, to reckon with my fundamentalist upbringing, my sexuality, my career shame, and my slow family tragedy, which would accelerate upon publication. It is what they call, I think, a burn book. In the time between when I had finished writing it and when it was published, I felt I could die. Fulfillment felt salvific to me, an act which moves immediately into perfect tense: “it is done,” like it says in the bible. It was crucial to my psychology to have a say, to have had a say, to say what I knew, to have said what I know, uncredentialed by institutions that had rejected me, to show up in a milieu unaffiliated, and unbeholden to future prospects, of which there were none. I couldn’t have been more mortified by my failures, and at the bottom already I tapped into the righteousness of abasement.

I had the right to say nothing at all. Neither John nor I was obligated to answer aloud, so we each resorted to writing in a clear hand a standard response on a small card and passing it, folded, silently across the table one perfect summer evening. We hoped it would satisfy my well-meaning new colleagues and their spouses, who were toasting our first week in Moscow and asking enthusiastically if the rumor was true that we’d found a home on Sixth Street. We wanted them to understand that we would be glad to discuss in places not as public as the open-air ice cream parlor the tactical measures we were necessarily taking since the sellers were part of NSA. We wanted please not to elaborate. The place was buzzing with generations of suspiciously large and wholesome families, not to mention the sticky children of literature professors, and it would be more than awkward to describe the extra steps a queer couple takes to obtain a home. It was both dangerous to the sale and embarrassing to me to describe how for months I presented myself as “a single unmarried man” (as it reads on the contract) in all the documentation with mortgage lenders and the phone calls with engineers and inspectors and insurers and in negotiations through our realtor with the Littlejohns, how for the first time in twenty years I went around anxious about pronouns: not feminine and masculine ones this time—singular and plural. Our public togetherness on a perfect summer evening was existentially a threat to what I had been compelled to attest; and what was risk, or defiance, or heroism, or cowardice was unbearably volatile in this story. Our friend Eileen joked, Yeah, it’s like: two bedroom, two bath—and how many closets does the house have: Oh right, the whole thing’s a closet. Calling out plainly the darker fear for the friend who hides it is a queer favor, a prerogative. Fronting is a good way to back out of a dream.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

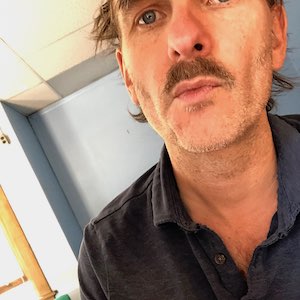

Poet and essayist Brian Blanchfield is the author of Proxies, a book part cultural close reading, part dicey autobiography. Recipient of a Whiting Award for nonfiction and the Academy of American Poets’ James Laughlin Award, he directs the MFA program at University of Idaho, in Moscow, where he and his partner John make their home.

46.730430, -116.989580