1. The Mondegreen Curse

My mom says I was a wedge. Wedged into her stomach, had made a decision never to leave, was being stubborn. Stubborn like an ox, and you haven’t changed a bit, she says. So, they cut her open and the sky poured out of her, so dazzling and luminous that the doctors went temporarily blind. Couldn’t see a thing. The Greeks called it amaurosis fugax, a fleeting darkening.

A river of light, my mom said. All different shades of bright blue, cascading out of my belly and flooding the room.

The doctors ran home and got sunglasses, but they weren’t enough. The light was so strong. One of the nurses was a metalsmith, she brought in two welding helmets. Those did the trick. The helmeted doctors returned to the delivery room. They found me and plucked me out, a tiny wedge nestled in a river of light.

“Sounds lovely. Like a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, something old and Germanic.”

Oh, I’m not being dramatic. And this is no fairy tale, this really happened. When the hospital workers in the maternity ward went home that night, all they could see were tiny dots of dancing color. Their eyes had been permanently damaged. My mom showed me how to see those colors—you close your eyes and ball your hands up into a fist and knead them into your sockets, like you do when you just wake up and are still very sleepy. Although, no one really does that except Shirley Temple in the movies, and she’s just being dramatic.

“Oh yes, I know about that. That technique is how Sir Isaac Newton first came up with the theory of light as wavelengths of color.”

Yes, her eyes look blue toned.

“No, Sir Isaac... never mind.”

Anyway, the doctors couldn’t get anything done, half-blind as they were. So they painted the whole town in patches of dull greys, deep navy and rich hematite, to give them a monochrome background they could focus on. And that’s why our land is colored this way.

2. The Mountbatten Curse

What happened was a man inherited a plot of land with a river running straight through it. How he got the land doesn’t matter, and what direction the river ran doesn’t either. Even the man’s estranged husband and their two-year-old daughter, Rose, don’t matter. What matters is the man began working the land, and sowing and plowing and fertilizing, with the intention to be a farmer and support himself.

What matters is this was the man’s way of proving to Cyrus, his husband (estranged, but not un-married), that he could be independent and responsible and self-sufficient and a ‘real’ adult. No, incorrect. It was his way of proving to himself that he could be independent and responsible and self-sufficient and a ‘real’ adult. Yes. Correct. That is what matters.

What happened next was that the man noticed the section of river he had planted crops by had begun to move. It didn’t move in a random direction, or due to erosion or heavy rains or another easily explainable reason. The river had moved, very specifically, away from where he had planted crops. Not very far, nothing that could be called a paranormal occurrence, or absolutely unheard of, but it had moved just far enough away to be of no use to the crops he was hoping to grow, the crops that would feed and sustain him physically and emotionally. The crops that took hard work, dedication, responsibility. The crops that, when Cyrus saw them, although this was definitely not their primary function, would enable him to understand that he had been wrong about the kind of person the man was, the man he was married to, estrangedly.

So great was the man’s determination—let’s call him Jim—so great was Jim’s determination that he didn’t get upset or lose hope when the river moved again, and then again. Jim simply replanted his seeds next to other parts of the river, then tried the opposite side of the river, before trying multiple locations at the same time. His determination was so great because these were no ordinary crops, Jim understood. Because of their significance, to Cyrus, to Rose, to their lives in the future that would either be together or not together, one or the other. Mostly it was important to himself, as once he had proven himself to himself, he would not only be a better possible lover/partner/father/etc., but also maybe wouldn’t need to prove himself to Cyrus or Rose or anyone else; perhaps he’d just be satisfied to live alone on this land forever, a successful farmer. A man who knows who he is.

This great determination, it not only gave the man infinite energy to start over again and again, it also gave him superpowers. Powers like: not worrying about time, not worrying that his months on the land had stretched into six years already. And like: not being overly concerned about the small stuff beyond his control. Many things fall into the category of ‘beyond one man’s control,’ and surely the myriad ways the river had shifted and splintered and truncated tributaries while growing others in seemingly impossible directions, always circumnavigating his crops or abandoning his crops or actually flowing away from his crops (however that was possible) fell squarely and definitively into the category of ‘beyond one’s control.’

Knowing that the rivers’ ways were a thing beyond his control, and responsible adults don’t get upset about things in that category, Jim took it in stride and spent another six years working on the land. The land was cleaved and divided, subdivided and partitioned, and the river continued to find (really ingenious, when you think about it) ways of circumnavigating and shirking, retreating and advancing, and generally being of no use to the crops, and therefore of no use to Jim and his endeavor.

Then one day Jim woke up and assessed what had become of his life on this cursed plot of fruitless, unproductive land. He assessed the decade spent on his enterprise, which seemed to have led nowhere at all. A flood of chaos came rushing into his head, a cacophony of doubts and questions and postulations that had mercifully left him alone for so many years. How was Cyrus, or better yet where was Cyrus, and how had he been? Was Cyrus with someone? Who was Rose, for she surely was a wholly different person at 14, and what did she think of him, if she thought of him at all? What of his own mother, who was ailing when he began on this land so long ago? Was she still sick, or dead? Had he abandoned her and left her to die? Who was he, after all of this time? Had he changed, was he different? Had these past years changed him, as he steadfastly believed they would, despite his inability to grow anything substantial? How, precisely, had he mustered the audacity to think he could do anything at all to change his trajectory or personality or essence in the first place? And at that very moment, on that very different and unusual day, Jim gave himself a choice: To return right this instant to whatever semblance of a life he’d left behind a decade ago, or to turn off the spigot of thoughts flooding his mind at the moment, just as the river had turned itself off so many times when he had needed it, and continue farming.

So he chose.

3. The Verdigris Curse

A small Turkish island just west of Kos, overlooking the Aegean Sea, is named after a larger, well-known Grecian island, which is named for a very famous king. No one was quite sure which island or which king, as the island’s inhabitants don’t have a great track record of bookkeeping or storytelling, which presents a problem when trying to give directions to people from outside of the island.

As such, it’s not uncommon to hear a conversation such as this on the docks of mainland Turkey:

“Just sail through the Kosian Strait, keeping the island Pserimos to your north, and in a few hours you’ll see it.”

See what?

“Our island.”

But what island is it?

“It’s a beautiful island, named for a famous king. The name will come to me in a while. I bet I’ll remember by the time you arrive.”

The island doesn’t have many visitors. This is just as well, as the residents don’t have much patience for outsiders and their obsession for naming everything, although they do swell like a rogue wave when thinking of the wonderful name for their own island, whatever it is.

The residents didn’t feel shame about their fugitive history and lack of knowledge about it. They have more important things to worry about. Like ensuring they’re flush with soccer cleats.

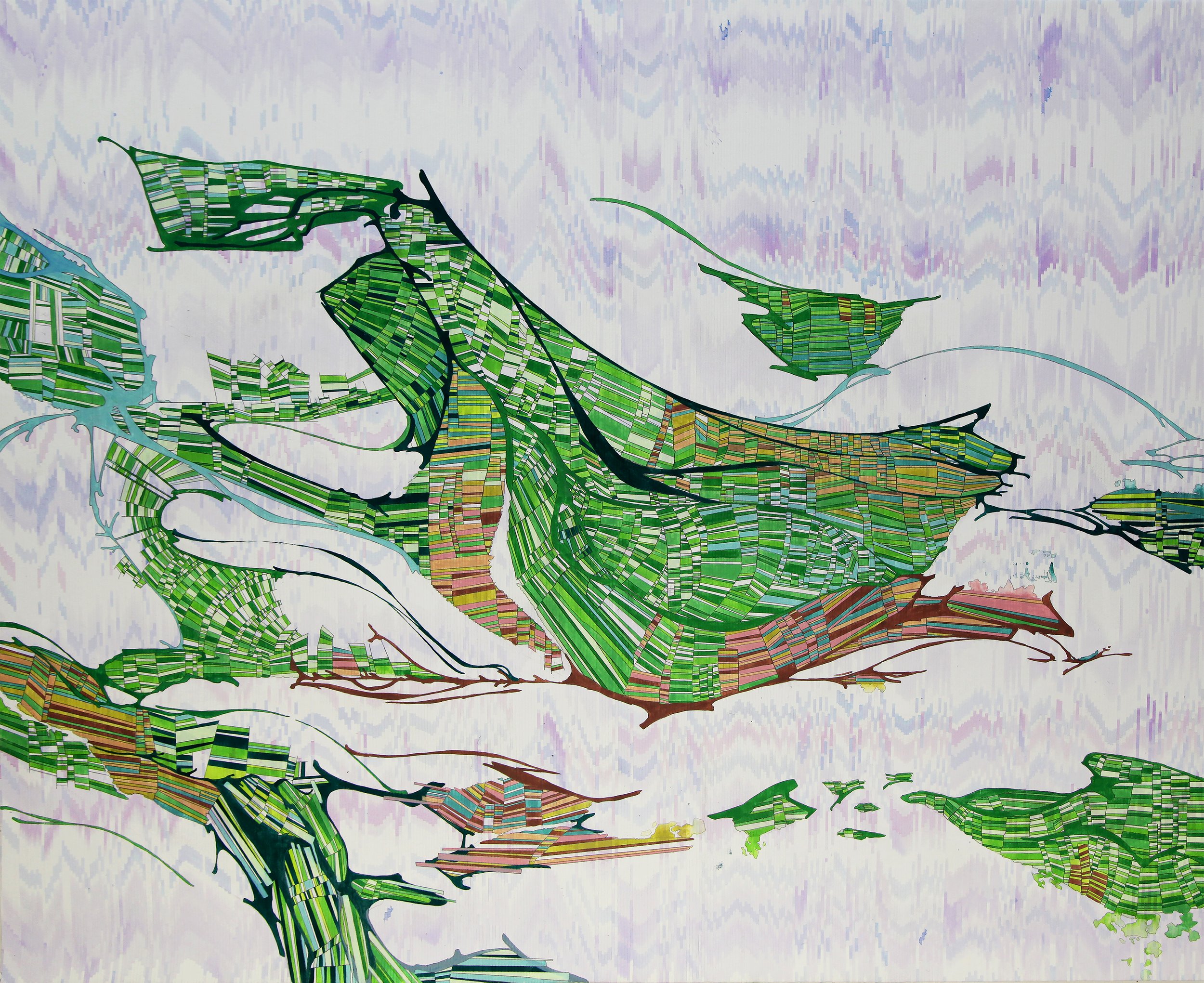

Unlike other islands in the Aegean, all craggy outcroppings and steep rocky cliffs, this island has rolling hills and wide steppes that seem to stretch on forever. Farm plots cover every conceivable surface, in complex geometric patches and large semicircles. From the air, the island appears lush and verdant, and you’d be forgiven for assuming that the land is bountiful. It is not. Unless you are in the business of wiring or plumbing, which most residents of this island are not.

The land there is so rich in copper that all of the grasses, clovers, mosses and plants on the island grow inebriated with the conductive mineral. It’s the naturally occurring patina of the copper that gives the land its verdigris sheen. It also makes it treacherous to walk upon. Even the youngest, most forgiving blades of grass slice through tender feet and obliterate shoes on account of their keen copper edges. Soccer cleats are the only shoes the residents have found that spare them the pain of navigating this pristine, treacherous land.

Did you know that soccer cleats were invented in 1526 by Cornelius Johnson, the royal shoemaker of a great and famous king? Was it the same king whose name was given to this gem of an island? Yes, perhaps it was, and perhaps one of these days someone will get around to looking him up and writing all of this down.

4. The Madder Curse

One summer my friend Sally and I decided to share a diary. We laid out some ground rules:

- Each person holds on to the diary for three days, then drops it off at the other’s house.

- Each person has to write at least one entry for each three-day possession, even if we don’t feel like writing and just write one word.

- We have to treat the diary like our own, meaning entries must be as open and honest as a private diary. If we feel inclined to share our deepest, most vulnerable thoughts, we must. And if one is inclined to go back and read earlier entries, we must believe with all our heart that we alone wrote them, and that was how we were feeling at the time.

Things were uneventful for the first few weeks, but after June 1st Sally stopped bringing the diary back to my house. Instead, after her three days were up, I’d find a note in my mailbox detailing a location in our town where she’d hid it for me to find. I was angry—this was not part of the rules. My parents kept a fold-out map of our town in the kitchen drawer that held all the pencils and take-out menus, so I pulled it out and used it to find my way to the diary. I tried to make a game of it, imagining that my friend was spontaneous and artistic and trying to make this more fun by sending me on little treasure hunts around town. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that she might also be toying with me, treating me like a pawn and seeing how long I’d keep retrieving the diary. I was nervous to say this to her, and by mid-July she no longer returned my calls or answered the door when I dropped the diary off at her house.

Sally’s moms were hardly ever around. One was a drunk and stayed out late, and the other never said much to me. Sometimes Sally showed up to school with bruises on her arms or legs. I know people think I was too young to figure out what this means, but I knew and all my classmates knew too. My parents weren’t drunks, and didn’t hit me, and talked and smiled a lot, so I tried really hard not to get mad at Sally. She had enough mad in her life. For that reason I never wrote the one thing in the diary I wanted to most.

Summers are supposed to be the best time of your life, and always go too fast. But when you’re feeling all alone and terrible, the days don’t go anywhere. This summer lasted forever. The map filled with marks on all the places I traveled to collect the diary, so I developed a system. I colored in each area depending on how far I needed to go. Pyrrole Orange if I could walk to where the diary was hidden. Tyrian Purple if I needed to ride my bike. Madder Carmine if I had to ask my mom for a ride; Yellow Ochre if I took the bus. I kept hoping the more time I put into coloring the map, the quicker time would pass and the better I’d feel, but this map didn’t seem to hold that kind of magic.

One day in August I arrived at Sally’s house and it was totally empty. When I collapsed on my bedroom floor in tears, my parents told me Sally’s family moved to California. I folded the map into the front cover of the notebook, and pushed it to the back of a high shelf in my closet.

Seven years passed before I took it out again. I read through all of the entries in one morning, searching for clues I might have missed and trying to remember how I really felt that summer. It’s a hard business, trying to re-feel a feeling you spent so much time trying to un-feel. When I finished reading, I unfolded the map, picked a colored spot, and walked there. It took me all day.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Tony Ingrisano’s paintings investigate the social and environmental structures that surround us, looking for new ways of visualizing these organizations. He has exhibited in group and solo exhibitions throughout New York City and Cleveland. Ingrisano is an Associate Professor and Chair of Painting at Cleveland Institute of Art.

36.90564, 27.06789

Location of The Verdigris Curse. A small, unassuming island where no one plays soccer.