What if there was a magnet at the bottom of a lake?

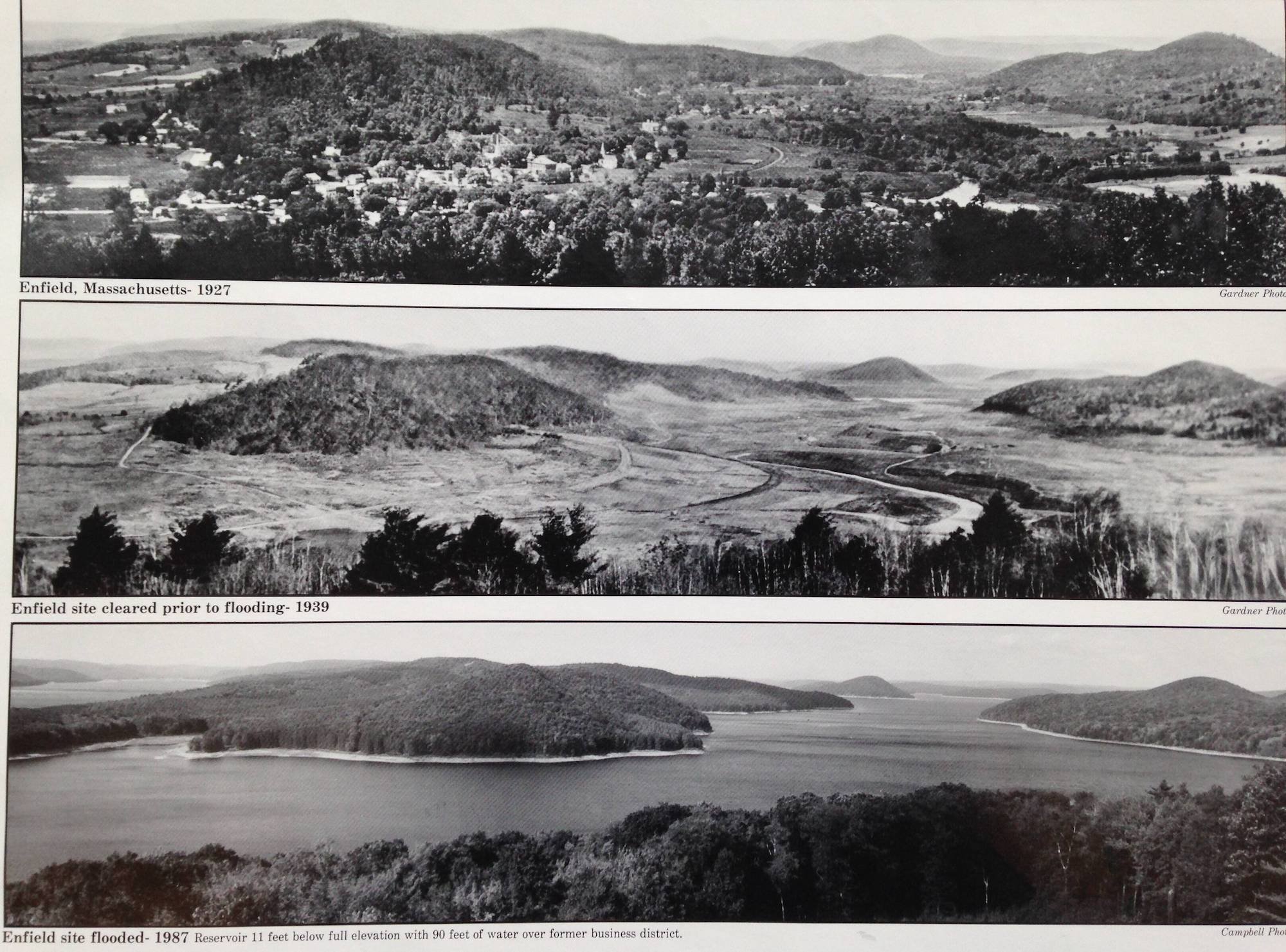

In 1938 the state of Massachusetts mandated the evacuation of the Swift River Valley and flooded it to create a new source of drinking water for Boston. Four towns were replaced by 400 billion gallons of water covering 40 square miles, an area roughly the size of the city it would trickle to, 65 miles away. A long gash of conservation lake and swampland runs up the middle of the state, south to north.

Churches, railroads, farms.

This ungrand canyon formally separates west from east and defines the liminal zone known as Central Massachusetts. Depending which part of the state you’re from, this place either has a name or it doesn’t. It either exists or it doesn’t. When you drink a glass of water in Boston you’re sipping on a lakeful of ghost towns. If you live in one of the places it flows to, the place it flows from doesn’t exist.

Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, Prescott.

It may take leaving to know the power of the magnet you’ve been near. You may forget what had been holding you. If home is an unwrecked ship. An anchor is a house for weight. How it holds the boat it smothers.

Access road. Acreage. Amherst. Ampersand. Anchor. Annex. Aqueduct. Archive. Ash. Authority. Athol. 32A.

We were bored. I mean everyone was bored but we were bored especially, how everyone thinks their adolescence is special, especially at the time. We liked learning to drive for the network of tunnels it opened up. We could travel through the woods inside the familiar dark, cutting paths through walls of trees. Blank and never ending. Closing like a hand around the car.

Red Slush Puppies with extra pumps of Shocker. Gas station burritos and weed. Maybe tonight we’ll steal another street sign. Chicken out at the last second and run like anybody’s watching. Skate the curbs at the bank and get called fags by shitfaced hicks. Stay up until dawn playing Donkey Kong in the attic above the garage. Remember how the 16-bit rain looked falling on the palm trees of Kongo Jungle? Yes. Of course. Forever. We were way too fucking high.

Could it have been anywhere else?

Backhoe. Backpack. Bald eagle. Band practice. Banishment. Barre. Basement. Battlestar. Belchertown. Bong water. Board slide. Bobcat. Boring. Bro.

It’s a puzzle, nothing like destiny, that brought my family to this place. All the blank grey pieces fit together to form no image. We move in to the quaint colonial town with the stone library and the bandstand on the common. I spend the year I should have started grade school roaming the house in tighty whities, playing video games and eating slices of Canadian White bread that I roll into the hardest little balls possible and eat while standing in front of the TV. The chew of it is sensational. My parents are the happiest they’ve ever been. My siblings are too young to remember.

All the houses are white. We attend concerts by the community band on the common in summer. Parents bring lawn chairs and drink beers in paper sleeves. Kids run laps around the wooden bandstand all night like some errant playschool mosh pit. The air is warm and wet and smoggy, sweet with kettle corn smoke in our noses. On the way in from the car I find a frog nestled in the grass and try to step on it when my mom yanks me away by the arm, tells me no. I pretend to tie my shoe so I can fall a bit behind her, her arms now full with lawn chairs and a cooler of juice and sandwiches. The frog is crushed to goop beneath the foxing’s edge on my Converse All-Star. Little clump of brown guts gleaming in the grass when I run to find her. I cry about this many times.

Our parents will divorce here. This house will fall to pieces. I will work at the country store off the common for a couple of years in high school after my mom moves us to the next town over. We learn only after leaving that the graveyards all have headstones with our last name.

Candy. Casket. Century. Chicopee. Church. Cochituate. Colony. Common. Connecticut. County. Coyote. Cradle. Crossing. Crow.

The first time I get high is in a car with distant friends. We have volunteered to help run a punk show at a DIY space in Worcester and are driving back through the wooded dark of Route 122. None of these people have faces I will remember, except Tony. Tony is the drummer in a ska band at my high school. Tony is approachable and goofy and wears a wallet chain and backpatched hoodie. His band is the first example I have of people my age playing music that actually sounds like music people might actually like to hear. We rent the local VFW and set up shows every other Friday. Folk, noise, hardcore, whatever. We charge $3 at the door. It is the only thing to do. Tony’s Corolla is not a bad place to get high for the first time. He steers with his knees while packing a bowl.

I realize I am stoned once the car slows from 45 to 30. I am picking another CD-R from the binder and only barely on the verge of panic. When I get home I look for Visine before saying goodnight to my mom, spending longer than usual on the edge of her bed, my head plopped in her lap. I wait for her to say something about my apparent physical condition. She doesn’t and I go up to my room feeling like I have passed through a shining portal.

My relationship with drugs does not mature with time. I spend sophomore year of high school pounding stale Keystones in the basement of whichever friend’s parents are away, smoking shitty weed from contraptions made of tinfoil and plastic bottles. None of us are very good with the mechanics of all this, but I am alarmingly talented at getting fucked up.

Maybe it’s Minor Threat, Black Flag, The Descendents. The cautionary tales my mom is fond of telling about the proclivity toward alcoholism in our family. The tendency of anxiety disorders to set on in adolescence. At 16 I decide that I am straightedge, remaining nailed to the X until my second year of college.

D-beat. Dam. Dana. Deciduous. Deer. Delay. Department of Conservation and Recreation. Dew. Dickhead. Dipstick. Discord. Distance. Distortion. Dork. Dumbass. Dumpster.

In 1931 the state of Connecticut sued Massachusetts for attempting to divert water it believed it ultimately had the right to. This water flows south from New Hampshire via the Connecticut River, breaking off in tributaries of the Ware and Swift Rivers that seep down into the valley. A proposed dam, needed for the creation of the Quabbin Reservoir, would stop the water from making its way down the middle of Connecticut, supplying hundreds of towns and farms before spilling into Long Island Sound and mixing with the salt of the Atlantic Ocean. The lawsuit is dismissed on the grounds that Boston needs it more, and as a compromise a limit is placed on how much water the dam will be able to keep from Connecticut and its eponymous snaking river: 20 million gallons per day.

The Winsor Dam is completed during the summer of 1939. On August 14, the diversion tunnel that had been redirecting the Swift River to allow for the dam’s construction is sealed off with a large rock. The valley begins to flood.

Eagle Hill. Eaglet. Eastward. Ebb. Egg sandwich. Elementary. Elevation. Elm. Enfield. Entrance. Erving. Estuary. Eventually. Exit 15. Exit 27. Extant. Ex.

The house on Washburn Road was haunted. Or at least it made sense to say so, so we did. About an hour’s meandering walk up from the center of town, past our old elementary school to the farmlands and hills where the capes and colonials stopped and the country lyrics began. The house looked normal enough at a distance, which is to say it looked like a house that was standing in a yard, though drawing closer would reveal most of its windows were blown out and it had long ago been abandoned. The front door would be unlocked so part of the deal was to walk up and push it open. Knock first if you want. But all the things you’d expect to see when you opened the front door to a house, like the insides of a house, of home as defined by familiar delineations and borders such as a ceiling, floor, and walls, were missing. The living room floor was gone so the front door just opened to a plane of empty air, occupied at its bottom by heaps of scrap wood, trash, and materials of the forest blown in to fill the basement over unknown years. Across the missing living room, hanging like a tongue, the staircase to the second floor dangled awkwardly from the ceiling. Late afternoons when we’d find ourselves there, weird light bleeding in through the broken windows and dust, you could gaze into the caverns of this moldering domestic structure like the inside of some big lit up tooth. All the craggy beerglass patterns. I’m not sure we understood. It was the presence of the absence, the standing solid void that we were seeing.

The summer before senior year, when we all worked at the farm, we planted some pot behind the haunted house. High-strung and sober, I’d nervously tag along on whatever misdemeanor projects my friends were cooking up, holding tight to the notion that I could always duck out and walk home. This love of walking would serve me forever, while a compulsive attention to escape routes would prove less helpful over the long run. We barely planted the little grey seeds, watering them once and expecting no results. It would not be the first time one of us bought shitty weed seeds from some burnout at our high school. But a few weeks later we returned to the abandoned house to find our dried out seeds had managed to produce a scrawny but otherwise healthy-looking marijuana tree, standing about four feet tall and swaying in plain view of the road. Reasoning this was officially more than any of us wanted to handle, the plant was promptly sold back to its burnout at a negligible margin of profit. He showed up that afternoon with some anonymous pimply friends, plucked the little tree and its roots from the yard and rolled the whole thing up into his Jansport.

Fanleaf. Failure. Farm. Fender. Fern. Fiction. Fill. Fir. Fish. Five. Fledgling. Flip phone. Flood. Flow. Force. Forest. Fork. Form. Fortune. Foundation. Four. Fowl. Frame. Franklin. Freeze. Friction. Friend. Frost. Fuck. Fun. Future. Fuzz.

After the dam’s completion it takes another seven years for the Swift River to backfill into the valley. By the time the official flooding begins, most residents of the four towns at its bottom have evacuated, their properties seized by the state under the terms of eminent domain to a total of 80,443 acres. As detailed in a pamphlet printed on recycled paper by Friends of Quabbin, Inc. and the Metropolitan District Commission Division of Watershed Management in 1991, the scope of this Original Taking included 2,500 people, 650 homes, 242 miles of highway, 31.5 miles of railroad track, and 7,613 gravesites at an average cost of $108 per acre.

As a kid I always imagined this as a single big event, a sudden biblical exodus of people out of a flooding valley, fleeing with water rapidly rising all around them. There would be houses, churches, graves left in their wake. Maybe someone lost their grip on someone’s hand and went sliding off a horse-drawn carriage to be sucked into the depths. There was a rumor that if the water got low enough a steeple could be seen poking up way out in the middle of the reservoir. While some minor semblances of this are true—who knows how many unmarked graves lay in the valley at the time of its flooding, or how much ancient trash was left behind in the process of residents leaving and workers clearing the land, plus all the regular death in the ground from 300 years of colonial disease and settlement—the reality is far less dramatic, and actually crushingly bureaucratic.

But when I talk with my friends from here we agree about the magnet. Something is terribly wrong with this place. Maybe this isn’t quite right, because it’s not really that explicit. Maybe you have to have lived here to feel it. Something off. A gentle field of static. The hum you don’t notice until the fluorescent light goes out. The fridge that kicks on and startles you. A ghost? We incline toward certain words when we can’t find better ones to explain. This may all be symptomatic of a complicated nostalgia, but that term would seem to imply an accompanying sense of belonging. There is a type of longing here, but its texture is reluctant and sore. Anchored in the flooded valley, is ours for the place we were or the places we were going? Would we become the landscape ourselves? All we thought we wanted was to leave.

Gap. Gate. Geese. Ghost. Girlfriend. Goats. Golden. Gone. Goodnough. Goof. Grass. Graveyard. Great horned owl. Greenfield. Greenwich. Grotto. Grove. Grownup. Guitar. Gut.

Cutting down 32A in the green Volvo wagon, the entire chassis of the car rumbles with each depression of the brake, a sure sign my rotors are completely worn to shit. I re-up the oil every few days and feed as much gas as a twenty can buy, as often as I can afford to spend one, which isn’t often at all. It’s the dead center of summer and we’re taking the long way I thought would be a shortcut back to my mom’s to get an amp from the basement. Thank my habit of forgetting only the most important details. We are supposed to be having band practice, but like most lessons in art making this one is all about process. A routine that’s annoyingly familiar and I feel a deepening sense of frustration at my galumphing absentmindedness. This sneaks out in bursts of damage to inanimate objects, gas pedal aggression, and pained exultations of FUCK spewed to the sky followed by a closing of eyes with hands on my head like I am getting busted while being hypnotized. I hate this behavior and the men it reminds me of. It is a pattern. I am such a fucking asshole.

Accepting that our afternoon of crafting juvenile noise rock and looking at flash videos on dial-up internet has become severely untenable, I pull off to one of the gate areas along a straight, empty stretch of road. We’re not close to the reservoir, exactly, but we’re at the mouth of one of its tunnely little entrances, access points demarcated by green and yellow iron barricades that lie at seemingly random intervals along its great amorphous border. I turn off the Lightning Bolt or Mr. Bungle or whatever arty experimental music we are listening to in front of each other at the time. Windows descend to a crushing wall of insect drones and the musk of warm earth, ambient signatures of northern woods in summertime seeping into the car. I scratch my head and suggest we walk around. This day is total bullshit. No one loves my idea but we all get out of the car. Not because I am convincing but because it is the only thing to do.

Hampshire. Hands. Hank’s Meadow. Happen. Hardwick. Harken. Harvest. Hawk. Hazelwood. Head rush. Heat lightning. Hills. Hilt. Hologram. Horses. Hubbardston. Hydrogen.

In the annals of memory one constructs a network of tunnels, of access roads and inlets to functionally travel across a murk of self-narration. To move across the delicate mirror surface without sinking in and having to remain. Despite our greatest efforts something always falls away, drifts to the bottom and is overcovered by tide and silt to become a stable part of the local ecology. I think this is what we feel humming in the ground here.

The lake. It has a forest floor.

Wandering the trails around the reservoir, its air is wet and buggy. The kind of overcast in summer that makes the forest turn to black. Walking through a tintype.

Ice. If. Igneous. Impotent. Indigenous. Infinite. Insignificant. Interior. Invalid. Ire. Is. Island. Isthmus. It. Itch.

The land around the Quabbin is remarkably pristine, especially considering how it lies at the heart of New England’s most populous state and feeds water to its largest city. Owing to the massive conservation effort required to keep the reservoir clean and drinkable, a diversity of plant and animal species populate the hills that abut its shores, spreading down into its waters in one continuous carpet of unspoiled natural life. All of this is surprisingly accessible, inside some rather stringent rules and regulations. Visitors are allowed from one hour before sunrise to one hour after sunset.

Running and walking are permitted. Snowshoeing is permitted. Biking and cross-country skiing are permitted within designated areas. Fishing is permitted, from the shoreline and from boats, motorized and un-, though restrictions apply to vessel size and engine displacement. Boats are only allowed for fishing. Hunting is permitted only during the annual Quabbin Controlled Deer Hunt. The permitting process is lengthy and selective.

55 gates along the perimeter of the watershed offer access to different tracts of preservation land. Some open onto roads and trails while others terminate in small pull-off areas with no discernable entry point in sight. The exact number of gates in total is hard to pin down, and is only shown in detail on an outdated map buried in the supplemental file directory of a state government website. Each gate is assigned a two-digit number for reference across disparate pamphlets and visitor’s brochures compiled for various recreational activities. One might suppose how a comprehensive public index of the Quabbin’s many entry points could constitute a potential security risk. Nowhere is this clearly stated, though its absence seems like evidence enough.

Jack pine. Jackass. Jailbird. Jake brake. Jaw harp. Jelly donut. Jerkoff. Jimbo. Jock. Joint. Joyride. Jug. Jumper cables. Jungle juice. Juniper. Junkyard. Just.

Dogs are not permitted. Swimming is not permitted. No grills, stoves, or fires are permitted of any kind. Camping is not permitted. All terrain vehicles are not permitted. Alcohol is not permitted. Drones and horses are not permitted. Private motorized boats must be permitted with the appropriate seal. No private un-motorized boats are permitted. Boats may only be launched from designated launch areas. Boat rentals are available at Boat Launches 2 and 3.

Katsura. KX80. Kayak. Keel. Keg. Kerosene. Kick flip. Kick start. Kids. Kill switch. Kingdom. Kittywake. Klepto. Knee. Knob. Knoll. Knot. Known. Knuckle.

The Nipmuc Indians who named this land Quabbin did so because the word meant, as best as can be translated, “the meeting of many waters.” The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, which mentions this in many visitor’s brochures, refers to it often as an “accidental wilderness,” of clear-cut New England reforesting itself within the watershed’s gates, deer and eagles retaking the hills.

It is important to note that these boundaries are all quite permeable. That despite a defined area of interior on a map and designated points of entry, the protected lands of the Quabbin Reservoir are not delineated by walls or fencing. Whatever lies inside is free to seep into the surroundings. This seepage mainly consists of regular New England wildlife and varietals of flora that already intermittently cover the land. But suppose whatever found its way out also carried whatever else had been ground into the soil. Whatever gloaming knowledges and shards of ancient memory.

I guess what I am saying is that I’m not sure what the accident is. And the eastern mountain lion, which was eradicated from Massachusetts under a state-sanctioned bounty hunting system and declared extinct in 1858, is occasionally spotted wandering the watershed interior.

Lag. Lake. Lame. Largemouth. Laugh. Leave. Lick. Limbic. Lip. List. Lock. Loom. Loon. Loser. Loss. Lug nut. Lump. Lungs.

When I do finally leave it’s on the morning after my eighteenth birthday, which happens to coincide with move-in day at the public liberal arts college where I’ve enrolled in the upper left hand corner of the state, 75 miles away. Since I have no concept of this not being far at all, I spend the night before trying to force a celebration with my friends. I’m still terrified of drugs and alcohol so we walk the quiet grass of our hometown’s common in the dark, smoking strawberry cigars legally purchased for the first time. I’m happy to be out of the house and away from my mom’s boyfriend, who I’ve been strategically avoiding for the last three years, and who lives with us in her detached bedroom above the garage. Sweet smoke in the warm air. We perch on the railing of the bandstand and watch the insects and cars trace their orbits through the night.

I try to think of what I’ll take from here. The small town cops, the rednecks and jocks. Punches in the stomach between classes in the halls. Adult men who’d lean out their truck windows to yell faggot or chase us on our bikes, letting up quickly because the initiation was also the follow-through. That time with the paintball gun. The best was on Halloween, when the one dressed up like a penis caught us outside the bar. He had this Band-Aid colored polyester onesie on with two little circles on his shoes that were supposed to be the balls. He slapped Jonny’s cigarette out of his mouth and asked what was he, fucking twelve? Jonny said he was nine.

None of these events devolve into a violence worth anthologizing. There is the occasional pickup with a confederate flag but no physical consequence for anyone. Just bored kids and drunk townies and the inverse and reverse, stuck in the same town at the same time for no reason. I feel scared and relieved to be leaving it now, to go to this school I got into because it was still taking applications when all my others got rejected. It’s Sunday night so the party ends early. I walk back up to the house and my friends get rides back home. My girlfriend breaks up with me over the phone on my second night in North Adams. The sun in a valley sets an hour before it does everywhere else.

Mailbox. Map. Margin. Marigold. Marker. Mass. Meadow. Meet. Meter. Mint. Missile. Mold. Mole. Money. Moose. Morning. Mortgage. Moth. Mountain. Muck. Mud. Must. Myth.

You think you can trade a place, one valley for another, and subsequent valleys for the valleys after that. But a place is something different. A location you can leave. A place, you never escape.

The Hoosac Tunnel is a 4-mile stretch of railroad driven through the base of a mountain in 1875 in the nation’s first commercial use of dynamite. The 196 workers who died building it are memorialized on a plaque in the city center, kitty corner to a long-defunct theater and an alarmingly affordable hotdog joint. Over the course of its 22-year construction, the project came to be known locally as “the bloody pit.” A different kind of mishap from the “accidental wilderness” of the flooded towns in the DCR pamphlet. I find it very alarming. Not because of the grim nature of these facts but because of their relative lack of hold on me, despite the fact that I live right down the street from where they happened. All this actual death in the hills and I can’t even get myself spooked. Meanwhile successful municipal water projects seem to leave me permanently haunted. At the bottom of this pit I spend a freshman year slugging forties and watching trains pass through to the other places they’re headed. A shady kind of loneliness colors the air. I never account for the spelling difference between Hoosic and Hoosac on the road signs, though I do learn that Hoosac is an Algonquin word meaning “place of stones.” I search for other events worth mentioning.

The Top of The World is a clearing by a radio tower on the eastern ridge that was always a good place to make a fire, drink, and watch the valley darken. Some years later I will stand there with my wife and watch a man attached to a yellow hang glider catch a running start from the tree line and fling himself down into it.

Nail gun. Narc. Nasty. Neck. Nest. New Hampshire. New Salem. Newt. Next. Nichewaug. Nip. Nipmuc. Non. North. Nowhere. Null. Numb. Number. Nuts. 122 N.

The Quabbin Aqueduct carries water from Central Mass to Boston thanks to a natural syphon effect. Water flows uphill without mechanical intervention and is circulated at the Oakdale power station to generate electricity, a carbon net positive. It is treated at the John J. Carroll Water Treatment plant in Marlborough with a course of sodium carbonate, carbon dioxide, chlorine, ozone, ammonia, fluoride, sodium bisulfate (to remove ozone), and ultraviolet light. It enters the Metrowest Tunnel and Hultman Aqueduct underneath Framingham and sits in covered tanks waiting to run into Boston’s hydro subsystems to the north and south of the city. A small amount of water is allowed to flow west by way of the William A. Brutsch Water Treatment Facility in Ware. This water receives a dose of chlorine and ultraviolet light before exiting via the Chicopee Valley Aqueduct. Towns beyond this point treat their water themselves.

Oaf. Oakdale. Oblong. Obliged. Ocean. Octave. Odd job. Odor. Offing. Ogre. OK. Old. Oops. Orange. Order. Ouch. Outer. Owl. Oxygen.

In Boston I believe I have escaped the pull of valleys and whatever lives inside them. The air is cool and salty from pressure fields swirling off the coast, and in summer a natural AC plugs itself in every night beside the river. I ride there on my bike after work, find a bench and watch the sloops get tossed and rattled in the waves. Head home once it’s dark to play music and hang with everybody. There are beers on the porch and cigarettes from the Irish bodega. Our landlord keeps the apartment crumbling and we all pack in to skew the rent correspondingly low. We have a practice space in Charlestown. I feel really good for a few years. Maybe the best I ever have. While I am showering myself in the water from the valley. Drinking the ghosts every morning and freezing them into ice cubes and brewing them into coffee.

Seven years after being cleared, the Swift River Valley is finally flooded full. Hills and peaks become islands. Prescott Ridge becomes Prescott Peninsula. The Quabbin Reservoir reaches 151 feet at its deepest point and is ringed by 118 miles of jagged forest shoreline, not counting the islands. It has a total surface area of 25,000 acres and when at full capacity its top inch contains 750 million gallons of water. Islands contribute another 63 miles to the shoreline figure, plus another 3,500 acres of waterlocked land.

For a short time in 1941, after being fully cleared of occupants but awaiting the flood, the land that would become Prescott Peninsula became the Quabbin Reservoir Precision Bombing and Gunnery Range, used for military training and target runs just prior to World War II. A joint study conducted in 2008 by Mass DCR, The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under the U.S. Department of Defense’s Formerly Used Defense Sites program concluded that munitions left in the reservoir from these exercises constitute no ongoing threat to the public. None of those explosives were live, but still, there are cartoon bombs stuck nose-first in the silt at the bottom of the Quabbin. Silently rusting away under a billion gallons of water.

Pack. Parch. Park. Part. Pass. Past. Path. Pax. Peel. Pent. Petersham. Pfft. Pickup. Pig. Pine. Pinhole. Pipe. Place. Plan. Pocumtuc. Porch. Posse. Poser. Prescott. Punk.

You may envision a multitude of ways out but an exit is not necessarily a means of escape. The water where I live now is stale and chemical-flavored, but watching droplets eek from a filter can become too much to bear. I shove my glass beneath the crystal flow of a wide-open tap. Warm and chlorinated. The Quabbin blinks in my head when I am drinking from Lake Eerie. From a sink in an apartment on Oakdale Road.

Quabbin. Quad. Quaint. Quarry. Quart. Quarter. Quartz. Queen. Queer. Quell. Quench. Query. Quest. Question. Quiet. Quip. Quit.

The reservoir itself is 18 miles long and 3 miles across at its widest point. These facts put in perspective just how small a state Massachusetts is, where three miles can constitute an utterly intractable distance. Were it not for the Quabbin Reservoir, all the one-hour drives that collectively scraped months from my life over two decades would have taken fifteen minutes. But three miles is an intractable distance when it’s an open sheet of glass. When it buries four towns and all the places we could have been from instead. When it is a black pool at night. And when the only lights that touch it are those of passing airplanes and pinhole stars a billion years away. I forget where I am when I realize this.

We claim this strange connection to the memory of the towns, as though having lived in their valley’s negative shadow has real bearing on our history. Whether the missing places in us have any correlation to the land depends. If space has a memory. If a void is a solid thing. We carry the loss of something we never had.

The Enfield town hall threw a farewell ball on April 27, 1938.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Zach Peckham is a writer and musician from Massachusetts who quit his marketing job to study poetry in Ohio. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in jubilat, Action, Spectacle, Poetry Northwest, Ghost City Review, American Book Review, @tuffpoems, and on the Academy of American Poets website.

42.41318070666372, -72.26351913409003

Certain areas of the Quabbin Reservoir have been hydronymized as “ponds.” Most correspond to actual bodies of water that predated the flooding or commemorate other important places and people. A few–“Sunk Pond,” “Dead Pond,” “Ash Pond”–seem to be jokes that can’t quite be parsed.