Legend

Arizona

If you live in a university town, you might walk around during the fall and see banners hung from the houses of different fraternity chapters to attract pledges. One sign I saw recently stated, “One Man Is No Man.” That’s Phi Delta Theta’s motto, I found out. The rhetoric, as far as the pledges were concerned, seemed clear enough: if you don’t join, good luck surviving out there on your own. Under a more cynical frame of mind, I might say the sign encouraged conformity. That individuality is inconsequentiality.

These phrases tend to stick and then slightly transform themselves in my mind and so all throughout the fall, as Nick and I were compiling Territory’s third issue in which we asked contributors to write about maps of Arizona, I repeated to myself “One man is no man” and then eventually “One map is no map.”

It’s trite, but true. Maps of Arizona usually define the state of Arizona. That is, they define a geographical invention made into a political entity. They draw its borders, its counties, its reservations, even its “point of origin,” as Caitlin Horrocks discovers in her essay “Baseline” (it’s Monument Hill, next to the Phoenix International Raceway, by the way). A map of Arizona connotes a certain point of view. If you don’t abide by it, good luck surviving out there on your own.

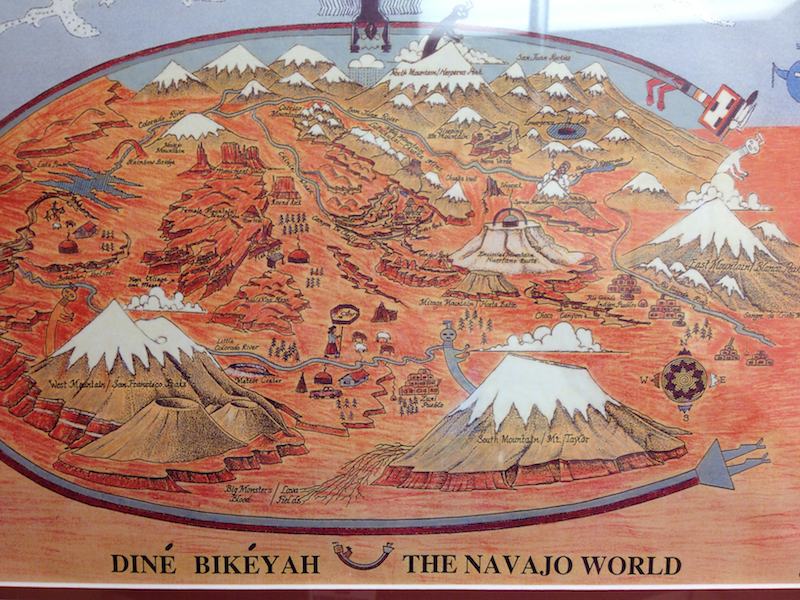

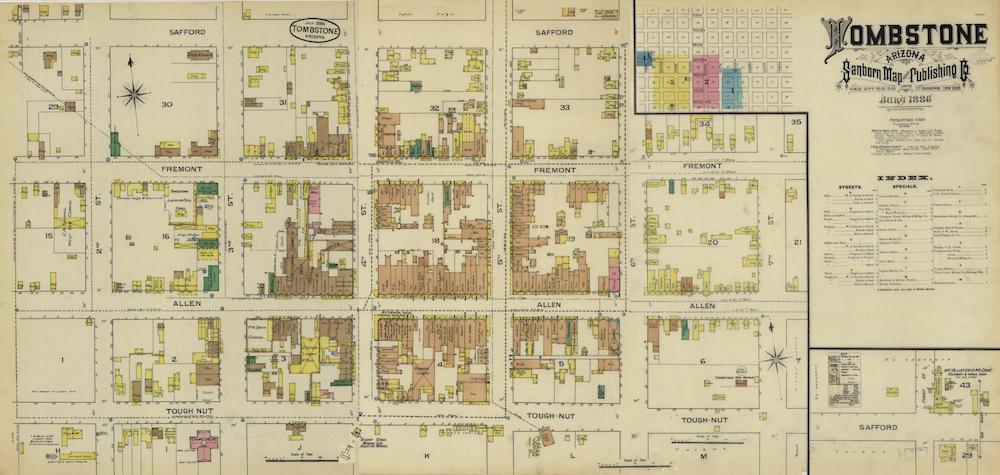

Of course, one Arizona is also no Arizona. The state seems a prime example of the insufficiency—the inequality and the exclusion—of one official, sanctioned map. As Justin St. Germain says of an 1879 Sanborn Company map of Tombstone: “If it were thirty-five years older, this map would show Mexico. Ten years older, a plateau called Goose Flats, and whatever white person made this map would’ve been too afraid of Apaches to make it.”  In other words, the name we use for the land carries with it many different manifestations, histories, and conceptions. If you call it Arizona, you could also call it Dinetah, or Sonora, or Territorio de Alta California. Heck, even if you call it Arizona, you may be referring to a Tohono O’odham phrase, alĭ ṣonak, meaning “small spring,” or the Basque word for “The Good Oak Tree.”

In other words, the name we use for the land carries with it many different manifestations, histories, and conceptions. If you call it Arizona, you could also call it Dinetah, or Sonora, or Territorio de Alta California. Heck, even if you call it Arizona, you may be referring to a Tohono O’odham phrase, alĭ ṣonak, meaning “small spring,” or the Basque word for “The Good Oak Tree.”

Arizona’s residents are constantly asked to redefine its borders. In her essay “Castaways,” Maya L. Kapoor learns that Barrio Viejo, her neighborhood in Tucson, is a “wandering barrio,” a geographical invention that changes as Tucson gentrifies and grows. “Barrio Viejo,” she writes, “is a new construct, given a name that sounds authentic. It is the shell of old neighborhoods, the carapace of communities long gone.”

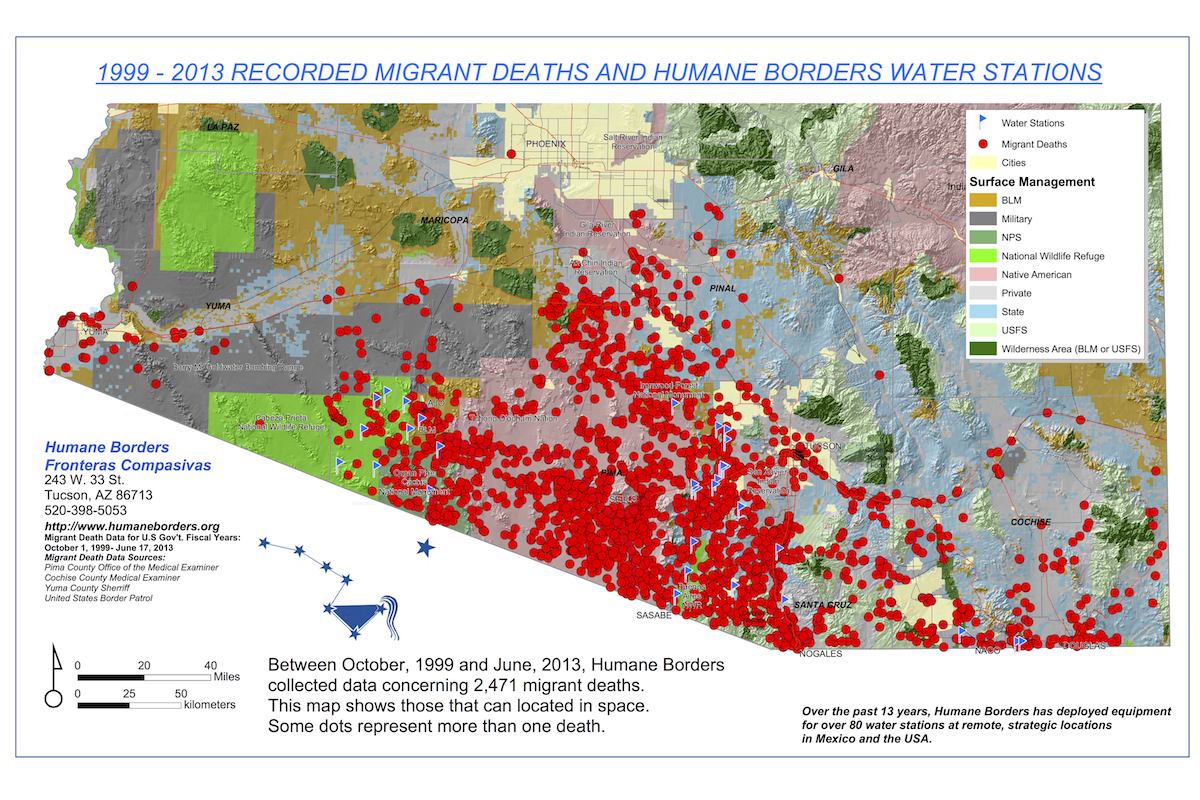

And in Francisco Cantú’s “Clearly Marked Ghosts,” the former Border Patrol agent examines the “monstrously abstract” red dots indicating migrant deaths on a Humane Borders map as he remembers the body of the first dead man he encountered in the desert: “I recalled my hand drawn maps and the thought of how incorrectly they presented the landscape, how wrong it was to represent this desert as anything other than a place marred by the profusion of wrongful and purposeful death.” Sometimes, one man isn’t no man. Sometimes, tragically, he’s many.

How then is it possible that we arrive at a single, capital-A Arizona? As part of the issue, we asked six writers to stow their smart phones and hit the highways for a summer road trip, using only a Rand McNally state road map as guide. We wanted to conduct an experiment.  What new Arizonas would they raise? What sort of map would their collective experience define?

What new Arizonas would they raise? What sort of map would their collective experience define?

“Easy to read, Folds out!” the Rand McNally map promised. But maybe the question is how a road map of Arizona became easy to read in the first place. It seems the geographies and histories of the state have never been particularly easy. Nor will they be. And as anyone who has used one of these maps knows, the problem is not in the unfolding, but the refolding, the puzzle of retracing your steps so you don’t wind up with a puffy accordion or an unlikely origami. Once it’s opened, there’s no way to un-use a map, to see the territory for itself. Such things are a mess, and hardly a job for one man.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to contruct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Francisco Cantú’s “Clearly Marked Ghosts” is a response to the Humane Border’s Lukeville Warning Poster that maps the deaths of hundreds of people who lost their lives crossing the border from Mexico in a remote corner of southwest Arizona, and a consideration of the author’s own mapping of the same terrain during his first year working for the US Border Patrol. The essay examines Cantú’s experience of seeing a dead body in the desert and his complicity in representing the landscape in a way that fails to acknowledge the ongoing accumulation of migrant deaths and the continued obfuscation of their individual narratives.

Francisco Cantú’s “Clearly Marked Ghosts” is a response to the Humane Border’s Lukeville Warning Poster that maps the deaths of hundreds of people who lost their lives crossing the border from Mexico in a remote corner of southwest Arizona, and a consideration of the author’s own mapping of the same terrain during his first year working for the US Border Patrol. The essay examines Cantú’s experience of seeing a dead body in the desert and his complicity in representing the landscape in a way that fails to acknowledge the ongoing accumulation of migrant deaths and the continued obfuscation of their individual narratives.

Cantú’s essay is written with an appreciation for the undertaking of the Arizona OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants, the result of ongoing partnership between the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner and Humane Borders, Inc.. Data compiled by this project has also been used by author Daniel Alarcón and data artist Josh Begley in their project “Fatal Migrations,” which offers an interactive satellite visualization of the physical terrain that corresponds to known locations of individual migrant deaths. In partnership with The Intercept and Field of Vision, Josh Begley has also recently compiled a 6-minute short film titled “Best of Luck with the Wall” that visualizes the entirety of the US/Mexico border using 200,000 satellite images taken from Google Maps.

Additional projects that have, in one way or another, recently sought to map the US/Mexico border include David Taylor’s Monuments, Richard Misrach and Guillermo Galindo’s Border Cantos, Rex Jones’ documentary La Frontera, and OpenStreetMap’s visualization of existing barriers and fencing along the entire 1,989 mile length of the border.

Cantú imagines the future existence of a collaborative open-source map that records the resting spots of deceased migrants while simultaneously representing their lives through multimedia narrative and documentary art in a way that invites the submission of personal remembrances, oral histories, photography, amateur film, collected ephemera, and the construction of real-world shrines marking their place of death.

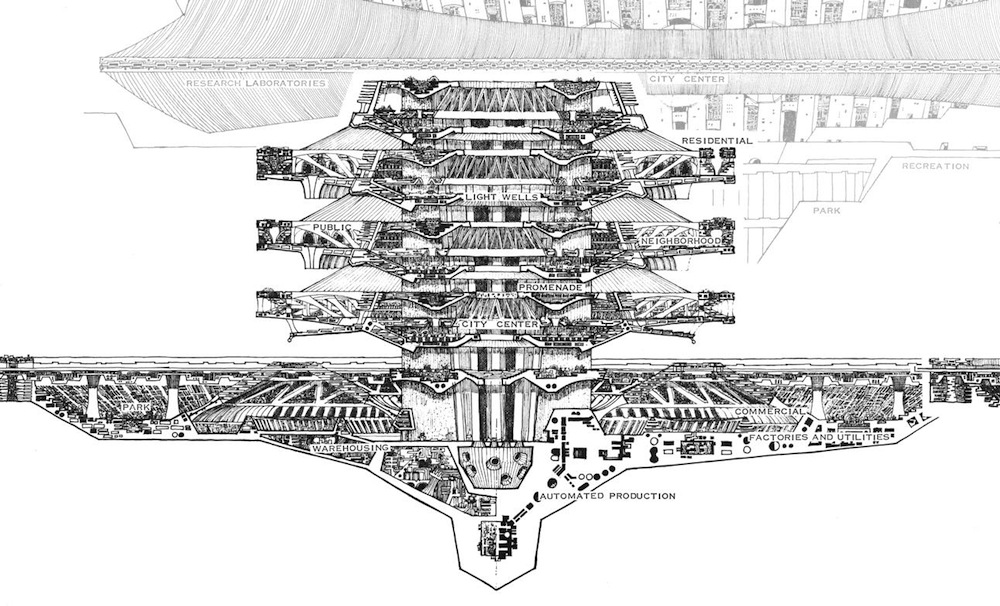

Will Cordeiro’s “Habitation for the Days”is a map of Arcosanti, guided by the commune’s blueprints and sketches, which were first compiled and published in 1969 by MIT Press in Arcology: The City in the Image of Man. This book is now sold through the Cosanti Foundation’s extensive online store where you can also buy calendars, posters, prints, and even Paolo Soleri’s original drawings (assuming you have $2,500 to $40,000).

Will Cordeiro’s “Habitation for the Days”is a map of Arcosanti, guided by the commune’s blueprints and sketches, which were first compiled and published in 1969 by MIT Press in Arcology: The City in the Image of Man. This book is now sold through the Cosanti Foundation’s extensive online store where you can also buy calendars, posters, prints, and even Paolo Soleri’s original drawings (assuming you have $2,500 to $40,000).

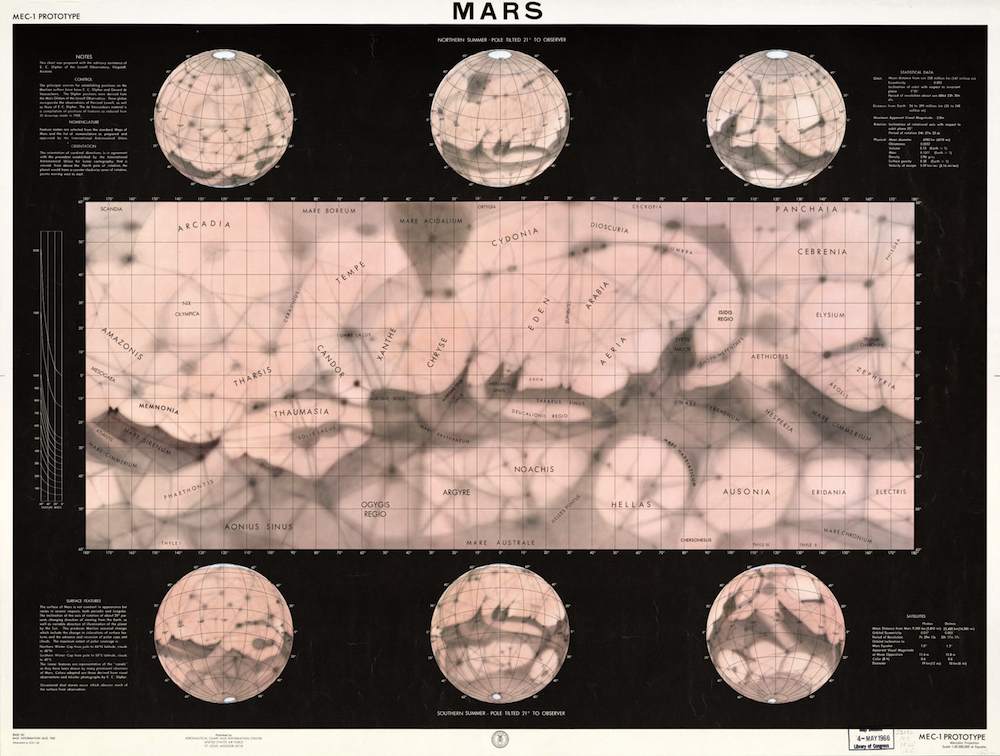

Emily Flamm’s “Prospects” is what its title describes, a collection of hopeful landmarks scattered throughout a vast, uninhabited landscape. There is a Tempe in Arizona, but also one on Mars, both named for the Vale of Tempe of Greek myth. Tempe, Olympus, Arcadia, Elysium, and Atlantis are all featured on the Mars: MEC-1 Prototype map, which was prepared by E.C. Slipher of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. Some of the most significant astronomical observations in history occurred there, but few have been attributed to the observatory’s namesake, Percival Lowell, who is remembered today more for his contributions to fiction rather than fact. Lowell believed the Martian canals he saw were irrigation systems built by an ancient civilization and many of the planet’s mountains and canyons have been named with this myth in mind. For more on Lowell and his Observatory, see Albert Goldbarth's essay “Worlds.”

Emily Flamm’s “Prospects” is what its title describes, a collection of hopeful landmarks scattered throughout a vast, uninhabited landscape. There is a Tempe in Arizona, but also one on Mars, both named for the Vale of Tempe of Greek myth. Tempe, Olympus, Arcadia, Elysium, and Atlantis are all featured on the Mars: MEC-1 Prototype map, which was prepared by E.C. Slipher of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. Some of the most significant astronomical observations in history occurred there, but few have been attributed to the observatory’s namesake, Percival Lowell, who is remembered today more for his contributions to fiction rather than fact. Lowell believed the Martian canals he saw were irrigation systems built by an ancient civilization and many of the planet’s mountains and canyons have been named with this myth in mind. For more on Lowell and his Observatory, see Albert Goldbarth's essay “Worlds.”

Caitlin Horrocks' “Baseline” features a detail of the 1968 Principal Meridians and Base Lines map created by the Bureau of Land Management. The inset is a product of the University of Oklahoma Press. Monument Hill, Arizona’s point of origin according to public land surveys, is bordered by a 198-acre Base and Meridian Wildlife Area. The Area, found at the confluence of the Gila and Salt Rivers, is classified as an Important Bird Area by the Audubon society given its hospitable riparian habitat and vegetation. In a way, this area too might be said to be a point of origin for the state.

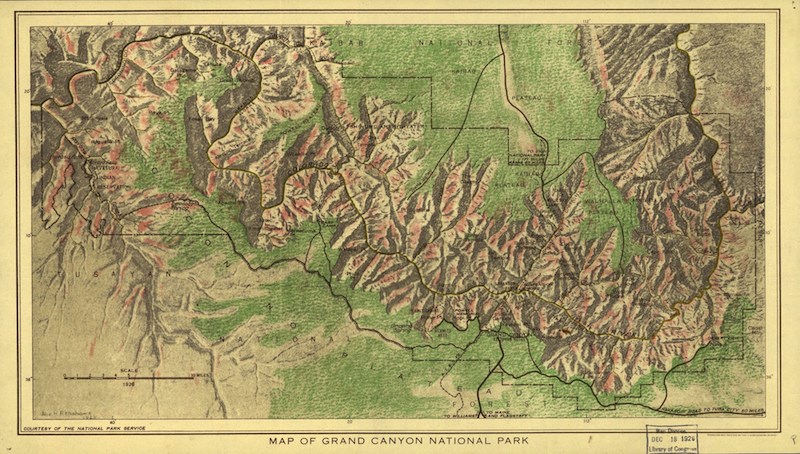

Allegra Hyde’s “Red Soil and Bones” explores Map of Grand Canyon National Park. This map is the result of an expedition organized by the United States Geological Survey in the summer of 1923 to survey the park. Nine men traveled down the Colorado River from Lees Ferry, AZ to Needles, CA as part of the surveying group. Included among them were Claude Birdseye, the expedition leader; Roland W. Burchard, the topographer and a man “of powerful physique, great endurance, and a cool steady head”; and Leigh Lint, the boatman and “a beefy athlete who could tear the rowlocks off a boat.” In a close-up of this map, a name and date appear in the bottom left-hand corner. They are all but indecipherable—Renshawn? Renshaver? 1923? 1947—though no options seem close to a name of the original crew.

Allegra Hyde’s “Red Soil and Bones” explores Map of Grand Canyon National Park. This map is the result of an expedition organized by the United States Geological Survey in the summer of 1923 to survey the park. Nine men traveled down the Colorado River from Lees Ferry, AZ to Needles, CA as part of the surveying group. Included among them were Claude Birdseye, the expedition leader; Roland W. Burchard, the topographer and a man “of powerful physique, great endurance, and a cool steady head”; and Leigh Lint, the boatman and “a beefy athlete who could tear the rowlocks off a boat.” In a close-up of this map, a name and date appear in the bottom left-hand corner. They are all but indecipherable—Renshawn? Renshaver? 1923? 1947—though no options seem close to a name of the original crew.

Maya L. Kapoor’s “The Castaways” adapts the images provided by Zillow in their "Recently Sold Homes in Barrio Viejo" listing. In March of this year, a 1,560 square foot home across the street from the El Tiradito shrine was sold for $299,000, somewhat above Zillow’s Zestimate® of $241,146. The house was built in 1948 and features great solar potential with a Sun Number™ score of 80. Had this house sold in August, 2008, Zillow estimates it would have cost $282,000. In April, 2012, $174,000. For a comprehensive history of redlining and housing discrimination, please see Mapping Inequality.

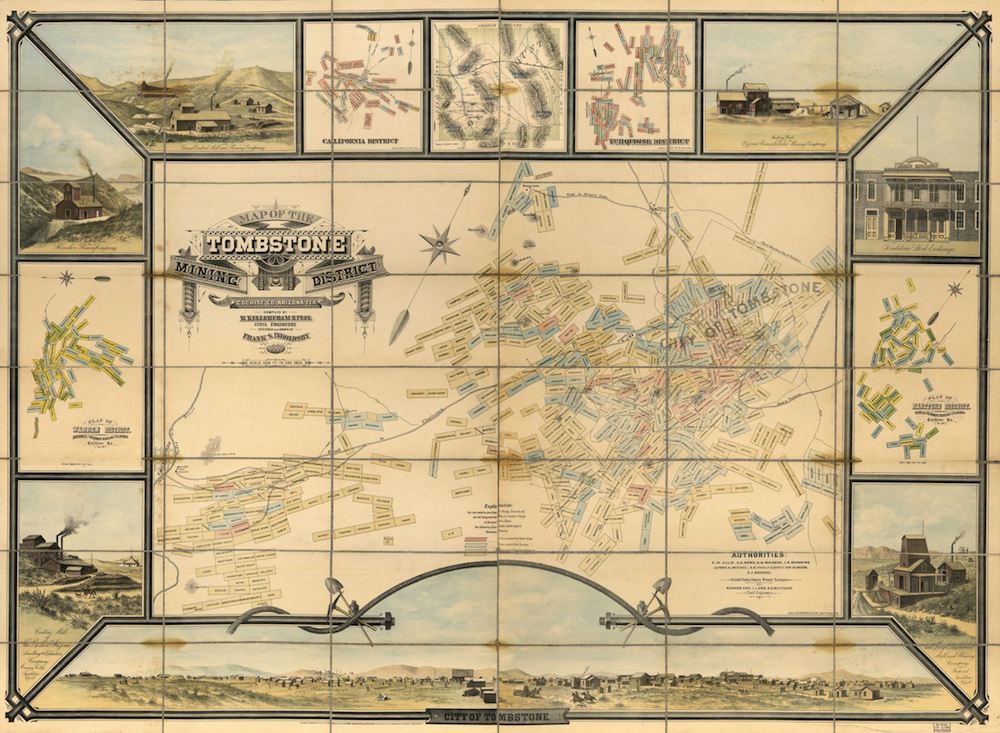

Sam Martone’s “Pretending” was inspired by Map of the Tombstone Mining District. The lithograph, published in 1881, details Tombstone’s mining claims: Owl’s Nest, Princess, Tranquility, New Year. It also depicts the claims of nearby districts in Cochise County: the Turquoise District, 18 miles north-east of Tombstone at the foot of the Dragoon mountains, California District, in the Chiricahua mountains, and the Hartford District, at the southern end of the Huachuca mountains. The map-maker and designer is one Frank S. Ingoldsby, a name that is, if not a pun, at least providential. Frank S. Ingoldsby is also the author of Railway Economics: A Treatise on the Problem of How to Increase the Earnings of Freight Equipment, recently re-released by the aptly named publisher Forgotten Books.

Sam Martone’s “Pretending” was inspired by Map of the Tombstone Mining District. The lithograph, published in 1881, details Tombstone’s mining claims: Owl’s Nest, Princess, Tranquility, New Year. It also depicts the claims of nearby districts in Cochise County: the Turquoise District, 18 miles north-east of Tombstone at the foot of the Dragoon mountains, California District, in the Chiricahua mountains, and the Hartford District, at the southern end of the Huachuca mountains. The map-maker and designer is one Frank S. Ingoldsby, a name that is, if not a pun, at least providential. Frank S. Ingoldsby is also the author of Railway Economics: A Treatise on the Problem of How to Increase the Earnings of Freight Equipment, recently re-released by the aptly named publisher Forgotten Books.

Manuel Muñoz’s “La Pura Verdad” is itself a map of the border between Mexico and the United States, but the exact territory being mapped depends on whose la pura verdad you trust. The mother insists on California. The father: Texas, then Arizona, then Texas again. Their son, the narrator, empathizes with both sides. As the mother explains, as much for her sake as her son's, it's easy to confuse "[d]esert towns with nothing around them and nothing to do." This mythic desert is similarly undecided in John Disturnell's 1846 map, Mapa de los Estados Unidos De Mejico, where the country’s northern border bleeds into the other Estados Unidos and over the frame of the map.

Manuel Muñoz’s “La Pura Verdad” is itself a map of the border between Mexico and the United States, but the exact territory being mapped depends on whose la pura verdad you trust. The mother insists on California. The father: Texas, then Arizona, then Texas again. Their son, the narrator, empathizes with both sides. As the mother explains, as much for her sake as her son's, it's easy to confuse "[d]esert towns with nothing around them and nothing to do." This mythic desert is similarly undecided in John Disturnell's 1846 map, Mapa de los Estados Unidos De Mejico, where the country’s northern border bleeds into the other Estados Unidos and over the frame of the map.

Justin St. Germain’s “A Real Community” explores The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Tombstone, Cochise County, Arizona, one of around 12,000 insurance maps made by the Sanborn Company. Daniel Alfred Sanborn, the company’s founder, drew his first fire insurance maps in 1866 while under contract from Aetna, just five years before the Great Chicago Fire. The first fire insurance maps were drawn in London in the late 18th century by the aptly named Phoenix Assurance Company. Although Sanborn maps provided a valuable tool for home and business owners, their primary purpose now is for historical research, a fate not unlike some of the towns they mapped, including Tombstone.

Justin St. Germain’s “A Real Community” explores The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Tombstone, Cochise County, Arizona, one of around 12,000 insurance maps made by the Sanborn Company. Daniel Alfred Sanborn, the company’s founder, drew his first fire insurance maps in 1866 while under contract from Aetna, just five years before the Great Chicago Fire. The first fire insurance maps were drawn in London in the late 18th century by the aptly named Phoenix Assurance Company. Although Sanborn maps provided a valuable tool for home and business owners, their primary purpose now is for historical research, a fate not unlike some of the towns they mapped, including Tombstone.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.