Materials

The Sanborn Company didn’t sell insurance; they sold maps to insurance companies. Supposedly, Sanborn sent a cartographer to every American city bigger than two thousand people, to see what they were worth. The cartographers were tourists, basically, except they cared about the buildings themselves, not what happened inside: what they were made of, what they were for, how much they’d cost to replace.

The book I’m reading, Valeria Luiselli’s Sidewalks, says maps are spatial abstractions, so putting a date on them contradicts their purpose. Only on a static, timeless surface can the mind roam freely.

Sanborn didn’t think so. Neither do I. The date was the first thing I noticed: July of 1886 was a strange time to send someone to map Tombstone.

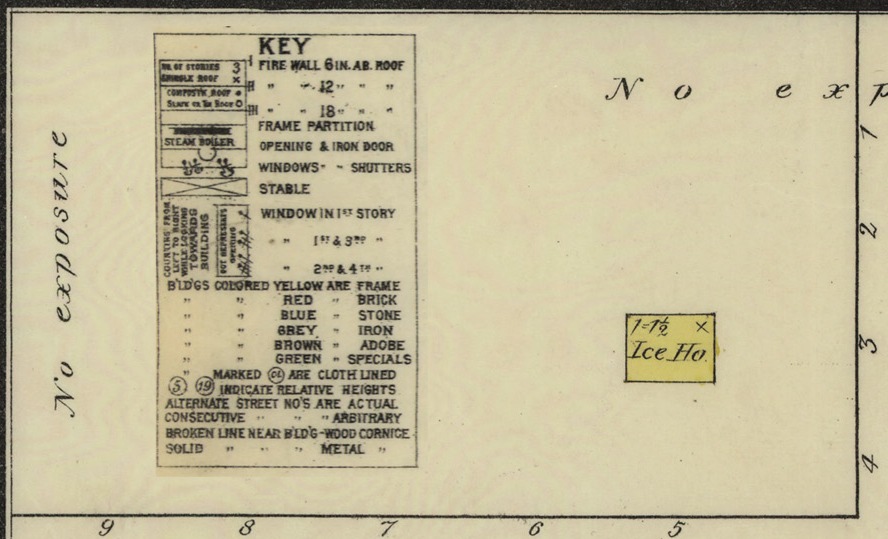

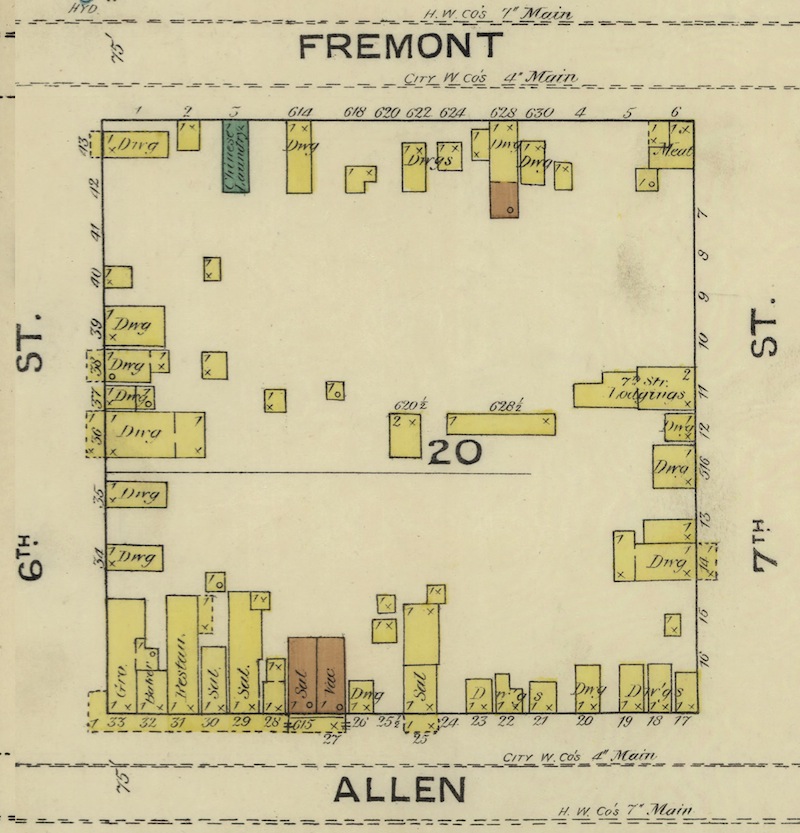

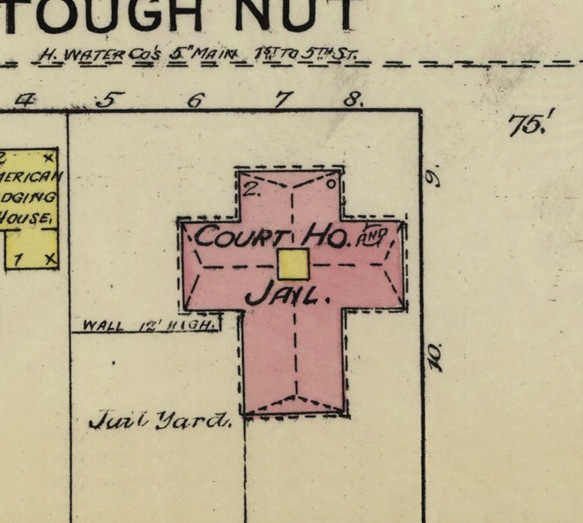

The key at bottom right explains the material logic of this map: yellow for wood frame, red for brick, blue for stone, gray for iron, brown for adobe, green for special materials.

The key at bottom right explains the material logic of this map: yellow for wood frame, red for brick, blue for stone, gray for iron, brown for adobe, green for special materials.

Most of the business district is brown. Without historical context, that doesn’t make much sense. Adobe is a lot of work: you have to dig the dirt, sift out rocks, mix it with water, form bricks and dry them. Then you still have to build the building. And it uses a lot of water, which was scarce in young Tombstone. Its main benefits are thermal mass and durability—neither of which mattered much in a mining boomtown with a mild climate—and fire resistance, which mattered a lot.

When this map was made, the city had existed for seven years and burned twice.

The first two times they built Tombstone, its builders used wood, denuding the nearby mountains of trees. If this map were made five years earlier, more of it would be yellow.

If it were made exactly five years earlier, weeks after the first fire, the east part of the business district would be burnt, or bare, or being rebuilt. Blocks 5 and 19 would be black, or the beige that signifies blankness here, or whatever color they used for buildings in progress; I don’t know all of Sanborn’s rules.

Four years earlier, the west half of town would be gone. The second great fire started in the heart of what’s shown here as block 4, and burned most of it, 17, and 18.

Four years earlier, the west half of town would be gone. The second great fire started in the heart of what’s shown here as block 4, and burned most of it, 17, and 18.

A famous picture taken after that fire shows the OK Corral sign unburnt above the charred ruins. Behind it stands an intact adobe wall.

Tombstone claims the largest adobe building in the United States. Schieffelin Hall, 5th and Fremont, northeast corner. I didn’t have to look that up on Wikipedia—you just sort of know that if you’ve lived there—but I also can’t find any other source. Does somebody keep a list?

Ever lived in an adobe? Open the doors, turn on a fan, it’ll stay cool all day long, even in summer. Put some music on: the acoustics are incredible. Bang your fist against the wall, feel how safe it feels.

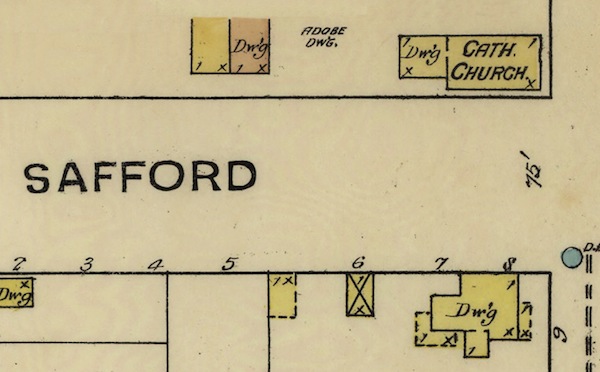

The first adobe I lived in was just off the edge of this map. See the Catholic Church in the northeast corner? Same block, north of that, a little west, I could see the cross on top from my bedroom window.  My bedroom had a trap door leading down into a sort of cellar, a vacant cube, probably where they got the dirt to build the house.

My bedroom had a trap door leading down into a sort of cellar, a vacant cube, probably where they got the dirt to build the house.

Early maps of Tombstone went deeper than this one, to map mining claims. The Gilded Age, the Mountain Maid, Toughnut, Lucky Cuss, Metallic Accident. Tributes to women, real or imagined: Laura Loise, Lalah Rooke, Jennie Bell, Nora, Emily, Aunt Sally. Some were less inventive: West Side, Hope, Silver Star. One smartass named the claim he surveyed Survey. The claim beneath my adobe was marked unknown. I think that’s where it was; those maps don’t show buildings, so it’s hard to say for sure.

Maybe that was the name: Unknown.

Not pictured: the mines, mostly south of town. The largest silver deposit in Arizona, a million tons of high-grade ore, remarkably pure and close to the surface. So was the water table—the mines first hit water at five hundred feet.

The oldest meaning of abstract is to remove something, literally to take away. Silver, for instance—mining companies abstracted Tombstone’s wealth.

Mineral rights are theoretically infinite, to an area’s “entire depth.” Even if you interpret that to mean to the center of the earth, that’s a few thousand miles. The deepest shaft in Tombstone was about a thousand feet. Its owners don’t know most of what they own.

Tunnels run beneath the entire town; Tombstone is literally undermined. The surface is always collapsing into the past. When I lived here, a sinkhole showed up one morning at 5th and Toughnut, southeast corner, where a carnival ride had been the night before; we circled the caution tape, trying to see the bottom. A few years later, another appeared a block west and threatened to swallow the Rosebush.

Purposes

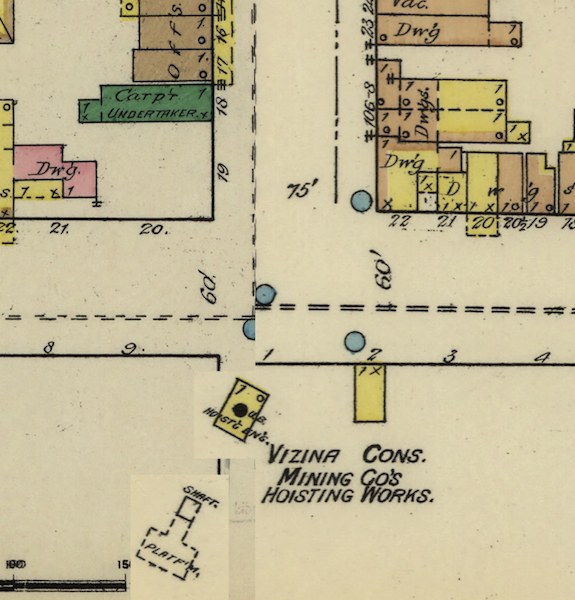

Not pictured: the World’s Largest Rosebush. Fourth and Toughnut—it’s one word now on the signs—northeast corner, out back of buildings 106-108. Planted a year before this map was made and still alive. Now it fills that yard and most of the former Pioneer Livery, eight thousand square feet, The World’s Largest Rosebush, according to Guinness. According to the signs that say according to Guinness. Five bucks gets you in. It’s free for locals.

Not pictured: the World’s Largest Rosebush. Fourth and Toughnut—it’s one word now on the signs—northeast corner, out back of buildings 106-108. Planted a year before this map was made and still alive. Now it fills that yard and most of the former Pioneer Livery, eight thousand square feet, The World’s Largest Rosebush, according to Guinness. According to the signs that say according to Guinness. Five bucks gets you in. It’s free for locals.

Schieffelin Hall, the largest adobe building in the United States, is mostly for locals. City Council meetings, Little League sign-up, that sort of thing. The last time I went inside was for a high school talent show. The last time I was outside, the Minutemen—the most famous of the border militias, a dubious honor indeed—were having their first meeting inside. A throng of protesters shut down the highway, and satellite trucks lined both sides of the street. The news that night showed Tombstone on maps, a red dot in the southeastern corner of Arizona, near Mexico.

If it were thirty-five years older, this map would show Mexico.

Ten years older, a plateau called Goose Flats, and whatever white person made this map would’ve been too afraid of Apaches to make it.

Five years and a few months older, it would show Tombstone’s exact peak. Veins spilling silver, the seat of a new county, the Gunfight brewing. No vacancy, more saloons, a bowling alley, casinos, restaurants, schools, churches, brothels, telephone poles going up. Lots more people, around ten thousand, although it’s hard to find an accurate figure, and locals make all sorts of claims, from credible to absurd.

They say it was once the biggest city between St. Louis and San Francisco, or sometimes just the fastest growing, whatever that means, however that’s measured: over what period of time?

Denver and Salt Lake are between St. Louis and San Francisco, and have always been bigger than Tombstone. Same goes for Minneapolis, Los Angeles, and Seattle, if you want to be a dick about it. But claims like that just keep on going.

They say Tombstone was once larger than San Francisco: local websites, travel guides, the since-defunct Tucson Citizen. Ridiculous. San Francisco had two hundred thousand people by 1880.

Richard Shelton says it in Going Back to Bisbee, a book I like despite its unflattering portrayal of my hometown. What do you expect from someone going to Bisbee?

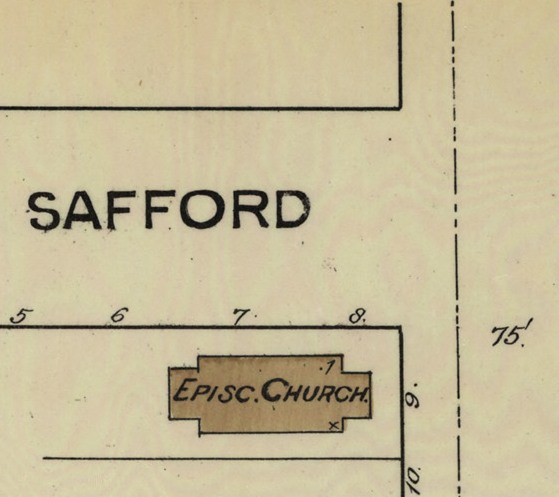

We used to give tourists false directions. Some RV would pull up to our baseball game outside the Episcopal Church—3rd and Safford—and ask for directions to Boothill, which is right on the highway, marked by a twelve-foot sign in the shape of a tombstone. We’d send them the other way, to Bisbee.

We used to give tourists false directions. Some RV would pull up to our baseball game outside the Episcopal Church—3rd and Safford—and ask for directions to Boothill, which is right on the highway, marked by a twelve-foot sign in the shape of a tombstone. We’d send them the other way, to Bisbee.

Not pictured: Bisbee, twenty miles south, Tombstone’s customary rival, an old copper town that reinvented itself as quaint and artsy. Now it has its own type of turquoise, the best restaurant in the county, a microbrewery.

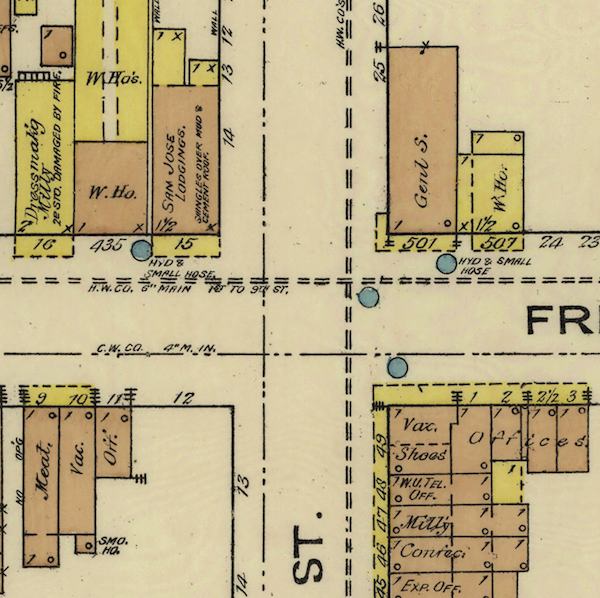

If you go to Tombstone, you’ll hear a lot about how many saloons it had. They’re marked Sal. on this map; I count twenty, including breweries. In 1881 there were supposedly a hundred and ten, one for every ninety people. It never struck me as a strange thing to brag about until I left.

These days Tombstone has maybe a dozen places to drink, about the same proportions. Some are the same ones—the Crystal Palace, 5th and Allen, northwest corner, one of my mom’s boyfriends used to own it—although most of them are for tourists. No stoplights, no grocery store, no proper doctor or dentist, nowhere to get a haircut. Just t-shirt shops and bars.

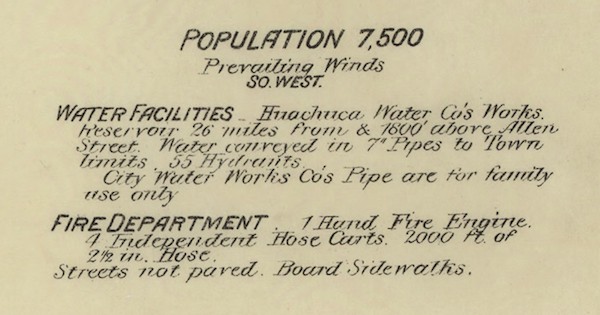

The blue circles are fire hydrants. The 26-mile water pipeline mentioned in Water Facilities at top right supplies them.  It was finished a few weeks after the second fire. One of the local newspapers joked that now locals could stop drinking so much whiskey.

It was finished a few weeks after the second fire. One of the local newspapers joked that now locals could stop drinking so much whiskey.

Locals mostly drink at Ringo’s. The original location is on this map, but it moved east of here a long time ago.

The east side of this map was the red light district. Those buildings in block 20 are euphemistically labeled dwellings. My high school was in that part of town; we had a few jokes about it. Last I heard, it was being converted into a brewery.

Tombstone’s brothels were famous, too. Supposedly, the New York Times once called the Bird Cage Theater—6th and Allen, southwest corner—the “wildest, wickedest night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast.” A local gift shop is named after a famous frontier madame; my family used to own it. The bar next door is named for a prostitute.

I searched the New York Times archive, but couldn’t find that quote about the Bird Cage.

They say Tombstone had hundreds of prostitutes. A historian whose family has lived here for a hundred years says it’s probably more like thirty-seven. There’s no way to know for sure. The census didn’t count women.

It only counted white men of voting age, so early population figures for Tombstone, including the one on this map, are worthless.

It only counted white men of voting age, so early population figures for Tombstone, including the one on this map, are worthless.

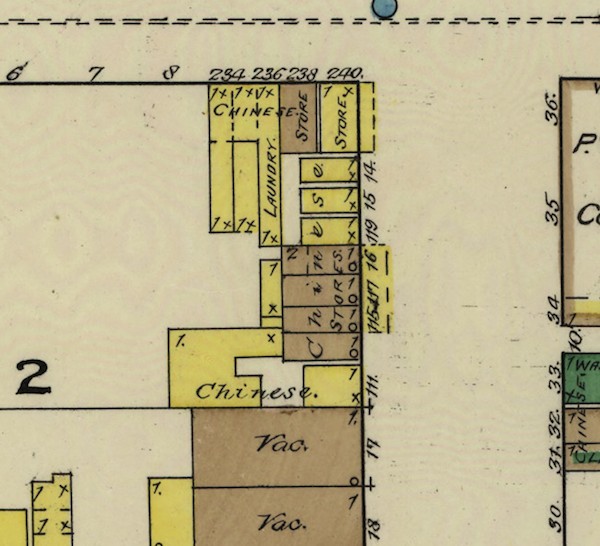

Between 2nd and 3rd, from Fremont south to Toughnut, some of the buildings are marked Chinese. This was the Chinese ghetto, known at the time as Hop Town, after the coeval street name for opium. Maybe you’ve seen the movie, the scene where the sheriff introduces himself to Wyatt Earp as president of the Anti-Chinese League. In fact, he was the founder. The mayor was president.

The Mexican-American parts of town were west and south of here, although nobody called them that. Cachoville still exists, across from the Circle K. It’s not on any map I’ve ever seen.

Tourists are not a demographic category, according to the Census Bureau. The number most often given is 400,000 of them a year. Which means they outnumber locals 300 to 1.

“Tombstone is a Real Community!”—actual section of the Chamber of Commerce website.

Cost of Replacement

The first time Tombstone burned down, a newspaper reporter estimated a hundred families homeless, three hundred grand in damages. The insurance companies paid one-fifth.

The second fire cost half a million. Insurance paid half of that. A reporter said individual losses were so heavy, they were impossible to recount.

Around that time water started rising in the mines. The companies imported pumps to keep it out. They ran constantly up on the hill southeast of town, abstracting the water.

A month before this map was made, the pumps burned, and the mines flooded.

Three years after this map, Sanborn came back to do another one. More than half of the white men were gone.

Three years after this map, Sanborn came back to do another one. More than half of the white men were gone.

Every town on a map is a ghost town.

The only accurate figure for how many tourists visit Tombstone is kept by the Courthouse, a state park. In 2014, it was 42,529.

In the last ten years, that number has fallen 28 percent.

Cochise County, which includes Tombstone, claims 1.3 million annual visitors. They spend almost $300 million annually.

Their median age is 55.

Not pictured: the site of the Gunfight. The OK Corral is on here, but it didn’t really happen there. The spot where it did is marked on every map of Tombstone now, often as a star.

Without tourists, this town would die; locals say that in every article about tourism, which has been dwindling for decades. The generation that grew up watching Westerns is dying off. Nobody cares about the Old West anymore except maybe Germans, and it’s a long way from Germany. Younger and wealthier tourists prefer Bisbee, with its antique stores and art galleries, its hotel of vintage Airstream trailers.

Last time I was in Arizona, I didn’t go to Tombstone. I went to Bisbee.

The per capita income for Tombstone residents is about sixteen thousand dollars. Five grand over the poverty threshold, ten under the national average.

Half the town works food service or retail.

I worked in five places on this map. All food service or retail.

I lived in three.

Not pictured: most of the places locals live. For instance: Holiday Ranch, northeast of here, a suburb of trailers and cheap lots for sale. Nothing out there is worth much. It might as well say Here be dragons.

My last map of Tombstone is sixteen years old. When I go back now, changes offend me. Sometimes I look at houses on online maps to see if I could afford to fix up one of those old adobes, spend summers there. I sound like such a tourist.

Not pictured: the motto the town came up with later, after the fires, after the mines closed, when Westerns went big and tourism saved it: The Town Too Tough to Die. It’s on the city seal.

The word tombstone probably originated in the practice of placing stones on top of tombs, to keep the dead from rising.

Not pictured: the graveyards. A persistent rumor—Shelton repeats it—claims that Boothill isn’t real, just a replica for tourists. Local historians say people are really buried there, but some tombstones might be in the wrong places. Boothill is a spatial abstraction.

Boothill filled in five years. They opened a new cemetery, but it’s only for locals. I’m not going to tell you where it is.

They say Tombstone is full of ghosts: in the Courthouse, Big Nose Kate’s, the Bird Cage Theater. Those ghost hunting shows come all the time. I never saw one.

They say Tombstone is full of ghosts: in the Courthouse, Big Nose Kate’s, the Bird Cage Theater. Those ghost hunting shows come all the time. I never saw one.

Tombstone has lost 12 percent of its population since 2000.

I want to believe I’m still a local, point to the tombstone tattooed on my arm. But I was never really local. You had to be born or buried there.

The word tombstone used to mean a coffin or its lid.

What do you call your hometown once you’ve left? Its name?

I never called it Tombstone. Not with a straight face. What a dumb fucking name. I don’t remember what I called it; back then, only other towns needed names.

Now I say near Tucson. This little town down by the border. In Arizona, I say southeast, outside Sierra Vista. When I tell the truth, I get lines from the movie—I’m your huckleberry—or those goddamned gun-shooting gestures I’ve even caught myself doing. Young people are easier to deal with; most of them have never heard of it.

Maybe they’ve seen the movie Tombstone—don’t get me started—and they picture that movie’s set, Mescal, a fake Old West town they used because Tombstone was too modern. It’s near Tucson.

They always ask: what’s it like to live in Tombstone? I don’t know, I say. Ask someone who lives there.

My map is different, more abstract. A scale the size of memory, how long I lived there, thirteen years, most of a childhood. What goes on it filtered by a local’s logic, a kind of love: familiarity, resentment, the secrets you know.

For instance: the bomb shelter. Deep in a shaft on Skyline Hill, off the southeast corner. We found it when we were kids, breaking into abandoned mines. It made sense in some ways: the nearby Army base, missile silos in the mountains, duck and cover drills in school, teachers telling us we’d die first. In other ways, not so much. Would a derelict mine hold up to a bomb? How many people did they ration for, and how long? Who would we tell about it if the sirens sounded?

Part of that’s easy: don’t tell the tourists.

And what if we survived, to emerge afterward and find our town burned again. No silver left, the tourists dead. Were we supposed to rebuild it? From what, and for whom? And who was going to pay for it?

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Justin St. Germain is the author of the memoir Son of a Gun. He attended Tombstone High School, the University of Arizona, and Stanford, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow. He teaches at Oregon State.

511 E. Bruce St., Tombstone, AZ 85638.

This is the adobe mentioned in the essay, where I lived as a kid. According to Google Earth, the current owners painted it pale green and built an addition, which probably violates its historic status.