In the Fall of 2015, I asked undergraduate students enrolled in my Honors English course at the University of Arizona to spend a semester thinking about maps and the stories they tell. Their first assignment was to choose a map and analyze its rhetoric: who is the map’s author, who is the map’s intended audience, what is the mapmaker’s purpose?

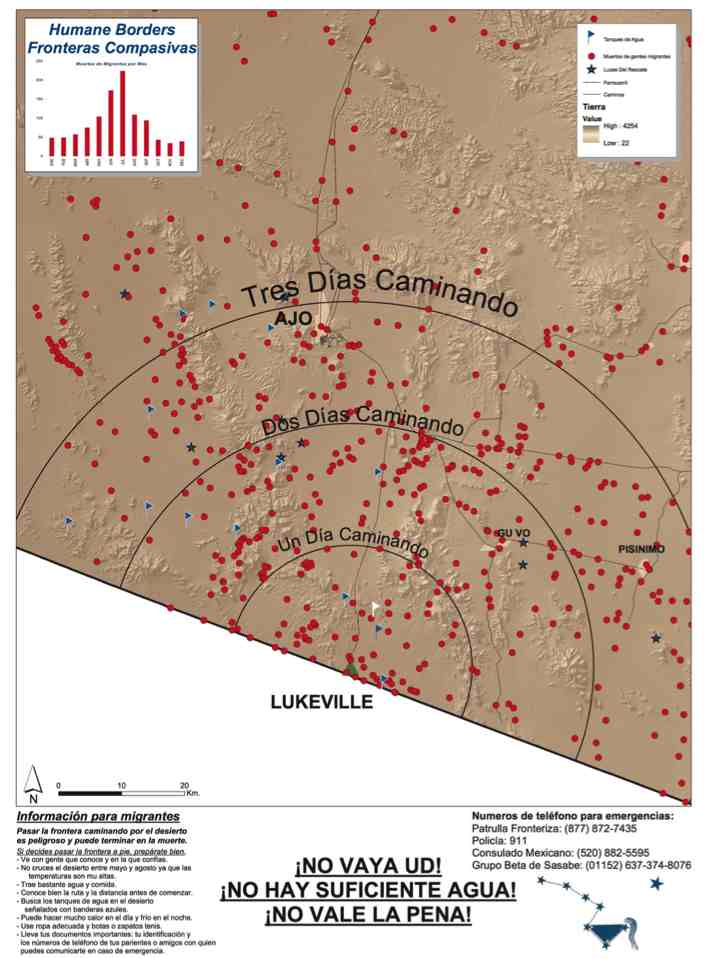

One of my students, a soft-spoken 40-year-old undergraduate from England named Rupert, was drawn to a map published by the non-profit humanitarian aid group Humane Borders.  The map he chose depicts the southwestern corner of Arizona and plots the deaths of undocumented migrants who lost their lives crossing the border in this remote tract of the Sonoran desert from 2000 through 2013. According to Humane Borders, the map was designed for distribution south of the U.S. border at shelters and other waypoints along the migrant trail.

The map he chose depicts the southwestern corner of Arizona and plots the deaths of undocumented migrants who lost their lives crossing the border in this remote tract of the Sonoran desert from 2000 through 2013. According to Humane Borders, the map was designed for distribution south of the U.S. border at shelters and other waypoints along the migrant trail.

The map is peppered with hundreds of red dots, each representing the GPS coordinates where the recovery of a dead body was reported by the U.S. Border Patrol, the Yuma County Sheriff, or the Medical Examiners of Pima and Maricopa counties. Also included are visual overlays indicating the number of days required to walk corresponding distances on the map, a bar graph representing the average number of deaths per month, and icons signaling the location of water tanks and rescue beacons.

In his rhetorical analysis of the map, Rupert describes it as a “warning poster…designed more to scare, reminding people what has to be faced.” He writes that “by presenting the deaths marked in red so prominently, along with the other data…this poster reads like a ‘keep out’ sign not dissimilar to the ones found on the boundaries of private property or on military land where unexploded ordnances may exist or where land mines are deliberately present.” Indeed, at the bottom of the map bolded text cautions potential crossers in all caps: DON’T GO! THERE’S NO WATER! IT’S NOT WORTH IT! Rupert also recognized that the map serves as more than a simple tool for dissuasion. “The map’s small red circles,” he writes, “mark points of departure from this life, acknowledging people’s previous existence, like memories remembered by family and friends. Usually with no form of identification, no passport, no driving license, these people are like ghosts to the authorities in this life, and the next.”

Rupert was one of those rare students who would frequently visit me during weekly office hours to discuss writing, share drafts of in-progress essays, and ask for detailed feedback for improving his work even after it had already been turned in and graded. When Rupert came in to discuss his analysis of the Humane Borders map, I acknowledged that he had chosen a map that broached a difficult and weighty subject. I struggled to find language that could acknowledge the dissociative nature of the map and recognize, at the same time, the reality of the plotted deaths, the individual and cumulative weight of each red dot.

Since Rupert was more than ten years my senior, I was careful not to speak to him in any way that might suggest I saw myself as more experienced or knowledgeable. Perhaps for this reason, as we sat in my office discussing the map’s two-dimensional abstraction and reproduction of human death, I declined to tell Rupert that I had spent years mapping this very same terrain by hand, that in traversing its landscape I had walked and driven past countless points of departure with little awareness of the lives that had blinked out there, or that I myself had once looked upon a dead body on the desert floor, that I could likely point to one of the map’s red dots and call to mind the very face of the man whose death it signified.

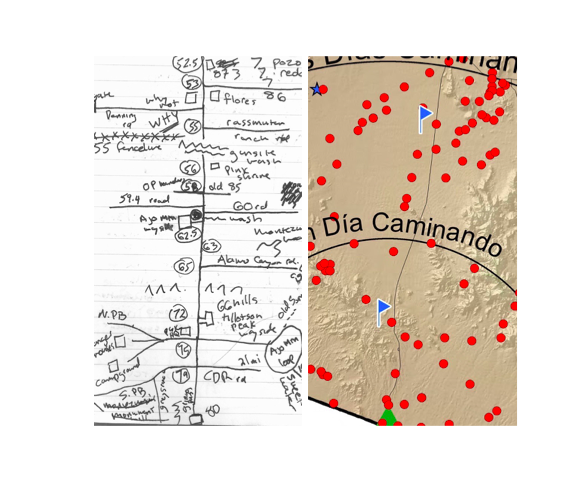

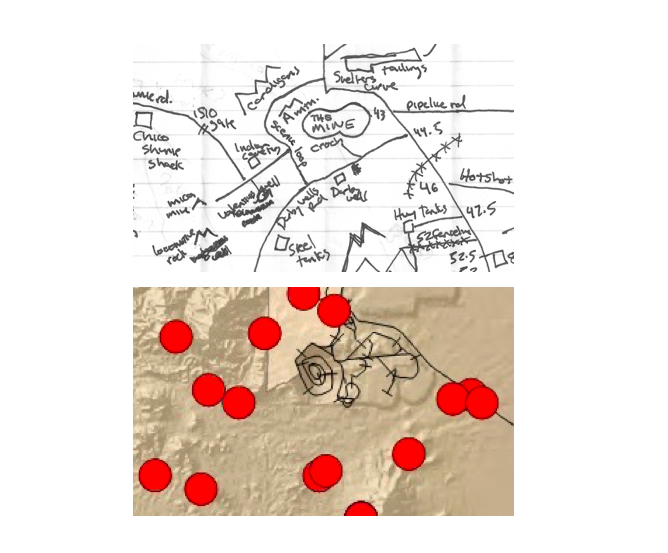

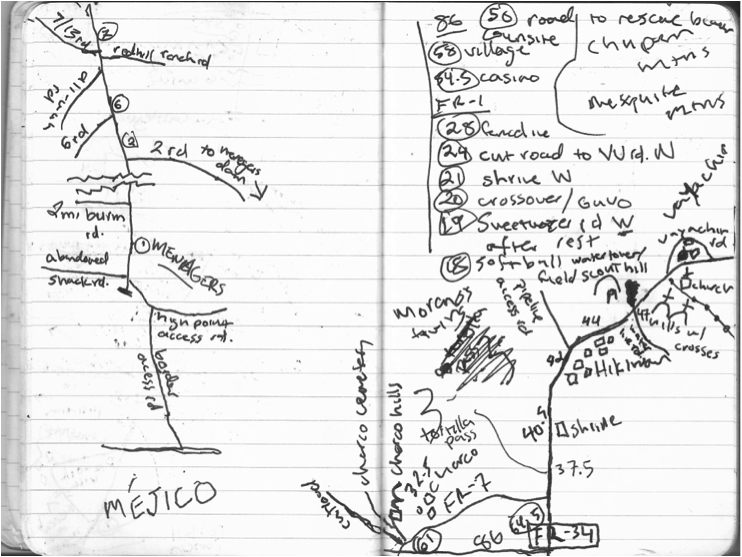

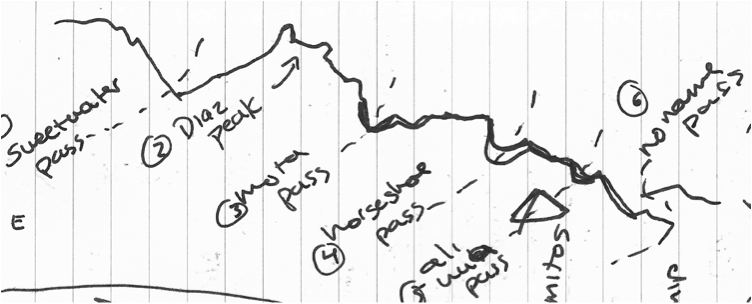

After graduating from the Border Patrol academy at 23 years old, I was sent to my duty station in southwestern Arizona and assigned to a field training unit alongside my academy classmates and other recently-arrived trainees. Our first weeks at the station were wholly dedicated to area orientation, and my first days with a badge and a gun were spent crammed into the back of lumbering patrol vehicles with my fellow trainees, furiously scribbling notes and sketching maps in a small notebook I carried with me in the cargo pocket of my rough duty pants. As we drove across uneven dirt roads, I filled pages with sloppy lines and quivering handwriting, glancing out the window and repeating place names as I scrawled them in my notebook: there is Diaz Peak, there is Black Mountain, here is Cameron’s Tank.

As we drove across uneven dirt roads, I filled pages with sloppy lines and quivering handwriting, glancing out the window and repeating place names as I scrawled them in my notebook: there is Diaz Peak, there is Black Mountain, here is Cameron’s Tank.

Among the most important information pressed upon us in those first weeks on the job were the names of prominent topographical features and man-made landmarks. We were prodded to study from all angles and directions the jagged ridge lines of desert mountain ranges, memorizing the myriad peaks and passes and holding in our minds the foot trails that crossed over them and snaked around their edges. We were made to memorize highway mile markers and corresponding side roads and were quizzed as to which pullouts were favored by drug smugglers and migrants lying in wait for their load vehicles. We were encouraged to see the landscape as crossers might, to look toward the horizon and discern a path of least resistance or a path of greatest obscurity, to recognize places of concealment and waypoints offering shade or a vantage point for surveying terrain,  to identify prominent features walkers might use to guide off while making their way through otherwise barren and indistinct stretches of desert.

to identify prominent features walkers might use to guide off while making their way through otherwise barren and indistinct stretches of desert.

As we traversed our station’s area of operations, the field training officers in charge of orienting us often recounted oral histories of the landscape, stories rooted in enforcement, pursuit, and death—here is where I was almost run over by smugglers, here is where I ran over a drunk Indian asleep on the road, here are the burned-out cars we lit on fire in the good old days, there is the water tower where agents on horseback captured 100 walkers, down there is where a group of migrants in torn clothing stumbled out of a canyon after being attacked by a jaguar, here is where an agent crashed into a cow and lost his life in the darkness of early morning. Other times senior agents would pass along strange and storied place names with little context, pointing toward locations known as the spooky forest, the trail of tears, purgatory, vampire village, Christmas gate, beef stew, dead man’s gap. We learned and mapped these places as the agents before us had, with little understanding of the larger narratives that might have surrounded their naming.

At the end of my shift, I would return to the empty house where I lived alone to draw and re-draw full-page maps of the terrain I had detailed in my pocket notebook. In a cavernous dining room, I sat delineating highways and dirt roads, fence lines and foot trails, peaks and mountain passes, thinking little of the deaths that had occurred there or those that were yet to come, thinking even less about the problematic way I was coming to understand the place, about my ignorance at the haunted and de-peopled nature of the landscape, about my own role in perpetuating the struggles that were playing out there. Traversing the landscape by day, I focused instead on naming and navigating space, avoiding questions about whether I was actually helping to interdict fatigued and dying crossers, or if avoidance of my presence was the very thing pushing them to their death.

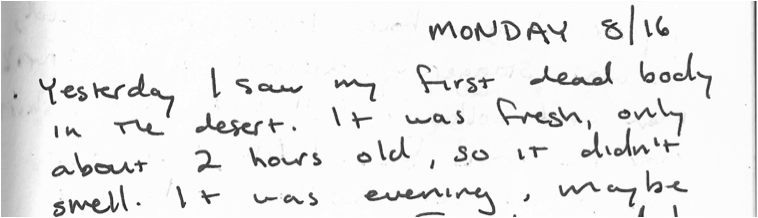

On August 15th, 2010, more than a year after finishing field training and being released for regular patrol, I saw my first dead body in the desert. The body was fresh, lying on a dirt two-track about a hundred yards south of a bend in Indian Route 23 where the road turned to snake through a chain of low desert hills. When I arrived on the scene, two boys—the dead man’s 16-year-old nephew and his 19-year-old friend, both of them from the same native village in the Mexican state of Veracruz—stood hovering above the dead man.

What I remember most from that day is the dead man’s face, his dark hair and long eyelashes, the way ants travelled in neat lines towards the foam drying at the corners of his mouth, the way the blood pooling in his body had formed a purple line at the sides of his abdomen, like a massive horizontal bruise. I remember, too, how the two boys traveling with him milled around his body and looked out dazed and devastated upon the desert as if they had been robbed by a faceless criminal. I remember how they asked me, naively, if they could come to the medical examiner’s office, if they could accompany the body back to Mexico, if they could bring the dead man back to his family in Veracruz.

What I remember most from that day is the dead man’s face, his dark hair and long eyelashes, the way ants travelled in neat lines towards the foam drying at the corners of his mouth, the way the blood pooling in his body had formed a purple line at the sides of his abdomen, like a massive horizontal bruise. I remember, too, how the two boys traveling with him milled around his body and looked out dazed and devastated upon the desert as if they had been robbed by a faceless criminal. I remember how they asked me, naively, if they could come to the medical examiner’s office, if they could accompany the body back to Mexico, if they could bring the dead man back to his family in Veracruz.

In his analysis of the Humane Borders map, Rupert referred to the red dots demarcating migrant deaths as “clearly marked ghosts,” small icons that “also indicate the invisible living men and women who were once walking with them at the time of their demise. The people that are still alive and walking.” Reading these words, I was made to think of the boys from Veracruz, and I wondered for the first time how they had borne the news of the man’s demise back to his village. I wondered whether or not they still carried his death in their hearts, if his loss had served to sway them from again attempting the journey or whether it had compelled them to stay once and for all in their homeland, all hope of opportunity and prosperity having withered from witnessing a manifestation of violence so seemingly casual, one that was somehow both wholly manmade and wholly natural.

In the weeks after I first read Rupert’s essay, I found myself imagining red dots hovering above the desert terrain where I had once worked. I imagined the landscape as a topography of death, a representation that was at once false and yet seemed to be somehow vital and urgently true. I sought to find a way of simultaneously holding memories of the terrain as it had been shown to me alongside images of the place as one with a multitude of deaths fixed upon the landscape. I recalled my hand drawn maps and thought of how incorrectly they presented the landscape, how wrong it was to represent this desert as anything other than a place marred by the profusion of wrongful and purposeless death.

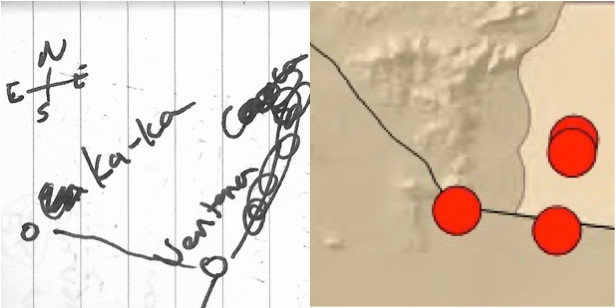

I wondered, too, about one particular red dot, the one that was, for me, less monstrously abstract than all the others. On a quiet afternoon, I finally sat down to find the very dot, calling up a high resolution image of the map on the Humane Borders website and zooming in on the terrain to trace the once familiar highways with my finger until I found the place where the road turned to snake through the low desert hills, brown and dappled on the map with dark shading, a place I had once mapped as little more than a thin line stretching west from the villages of Ventana.  Placing my finger upon the dot, I wondered how the entirety of a man’s life could be represented by a single point on the map, a red spot identical to hundreds of others flanking it on all sides.

Placing my finger upon the dot, I wondered how the entirety of a man’s life could be represented by a single point on the map, a red spot identical to hundreds of others flanking it on all sides.

In his book The Power of Maps, geographer Denis Wood asserts that “maps link the territory with what comes with it.” Thus, in the deadly borderlands of Arizona, perhaps any map that fails to acknowledge the dead—like those that filled my pocket notebook—could be seen as problematic or false. But the problem with a map of the dead is that the dead have no names, that their deaths are represented in the very same manner, that each individual is recognized only for their dying, as a “clearly marked ghost” fixed upon the landscape. In beholding a map of dead migrants, the viewer is encouraged to see those who have died crossing the desert in the same way that policy makers and law enforcement agents might see them, the way they are seen by militiamen and human traffickers—each indistinguishable from the next. Indeed, the role we are assigned in beholding a death does everything to determine how we hold it in our minds. As a uniformed agent standing above the body of a dead man all those years ago, I was somehow never compelled to ask his companions for his name, and even if I had, it would have been forgotten quickly and without ceremony.

More important than mapping the deaths of border crossers is preserving the names of those who have died and finding right ways of holding them in our minds, a way that allows us to rightly comprehend the spaces in which they have lost their lives. Just as important as their names, but harder to discern, are their stories. A worthwhile map of border deaths would cause us to feel something for each loss of life plotted upon it—it would cause us to feel necessarily overwhelmed by the amassing of red dots, by the accumulation of numbers and names, by stories with familiar and comprehensible details.

The importance of names and of holding space for distinct individuals is lost in the warning posters of Humane Borders, but not on the organization itself. Through a partnership with the Pima County Medical Examiner, Humane Borders maintains a constantly updated and searchable death map online where “viewers may see the exact location where each migrant body has been found, along with other information, such as the name and gender of the deceased (if known and if the family has been notified), date of discovery, and cause of death.” Such a tool allows us to interact with the red dots marking the departed, enables us to hold distinct names in our mind, and provides us with small pieces of information about individual lives—the closing details of stories we might someday seek to understand.

Nearly six years after his death, I drove west from Tucson to see if I could find my way across the desert to the place where the man from Veracruz had laid down to die. I drove along State Route 86 and entered the vast Tohono O’Odham Nation, continuing for over an hour until I reached Indian Route 34. I turned north, passing through long stretches of barren desert on my way to the villages of Hikiwan and Vayachin until I finally reached the junction of Indian Route 23, where I turned to drive toward the village of Ventana. As I drove west past the village, I began to recognize the low hills in the distance and I suddenly felt a strange weight, an awareness of the subtle distortions that reverberate in space long after one’s death. I drove slowly, nervous that I might not find the exact spot, that I might end up driving for miles wondering if it could have been here or if it might have been there. I began to feel alarmed that I might never stand again in the place where that man's life had ended, the place where his nephew and his companion had stood bewildered as I asked to them to explain how the man had met his end. But then, just before the bend in the road, I saw a dirt two-track splintering south into the creosote flats. I pulled my vehicle onto the dirt shoulder of the road and stepped outside to feel the hot summer wind. In the distance, clouds of clay-colored dust whipped into a tall funnel and then disappeared again at the horizon. As I walked south along the two-track my memories coalesced upon the terrain and I looked down to find the very patch of dirt where the man had laid on his back all those years ago with blood pooling in his abdomen and ants crawling across his face. I looked out at the landscape and said to myself—here is where Ascención Quechulpa Xicalhua ended his life’s journey, here is where his story rests upon the earth.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Francisco Cantú is an author and translator with an MFA in nonfiction from the University of Arizona. His essays and translations appear frequently in Guernica and his work can also be found in Best American Essays 2016, Ploughshares, Orion, and Public Books, where he serves as a contributing editor. A former Fulbright fellow, Cantú also served as a Border Patrol Agent for the United States Border Patrol from 2008-2012, working in the deserts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. A book about his time in the borderlands is forthcoming from Riverhead Books.