Due to natural obstructions, this road is not continuous.

Among their gods, the Romans worshipped Terminus, a god of borders. At his yearly festival Terminalia, people visited boundary markers to pay their respects. They offered sacrifices of sweet cakes and fruit: nothing living. It was considered unlucky to stain boundary stones with blood.

A legend relates that a temple was to be rebuilt and rededicated to Jupiter; the signs and symbols of other gods were to be removed. But the sanctuary of Terminus could not be budged. This was taken as a good omen, that the borders of the Roman state would be equally immoveable, equally eternal.

When I first moved to Tempe, Arizona, I was baffled by the radio traffic reports. Traffic was always slow at “The Stack,” but not as slow as at “The Mini-Stack.” There was the Durango Curve, the Superstition Transition, the Dreamy Draw. The Split, just north of Sky Harbor Airport. Sky Harbor: much of what lyricism Phoenix’s city-scape has to offer is transportation-related. Eventually I learned my way around, not just the roads themselves, nor even their names, but what people actually called them. I was both pleased and sorry: pleased, because I was becoming a local, solving small mysteries; sorry, because once I’d solved them, the mysteries vanished.

Before independence, the United States followed the English surveying practice of metes and bounds. A metes and bounds property description narrates boundaries using a combination of distances, compass bearings, landmarks, and natural features.

From a deed book for Hardy County, West Virginia: “BEGINNING at a stone pile, black oak and chestnut oak, a corner to the Mary M. Maphis land as per deed of 1889, and in the line of the 2399 acre tract, and running thence with Mary M. Maphis’ lines S. 14 45’ W. 88 poles to 4 pines; thence S. 51 W. 54 poles to a chestnut oak and stone piles, her corner, and a corner to C. Ed Martin tract; thence S. 45 W. 106.4 poles to a chestnut oak; thence S. 28 30’ W. 82 poles to a double birch and a locust, said Martin’s corner, and supposed to be in line of said 2399 acre tract…”

Old metes and bounds surveys can be comically inexact. Trees die, walls crumble, streams dry up or reroute themselves. Even compass bearings vary slightly over time. True north is not true, as least not as described in property assessments.

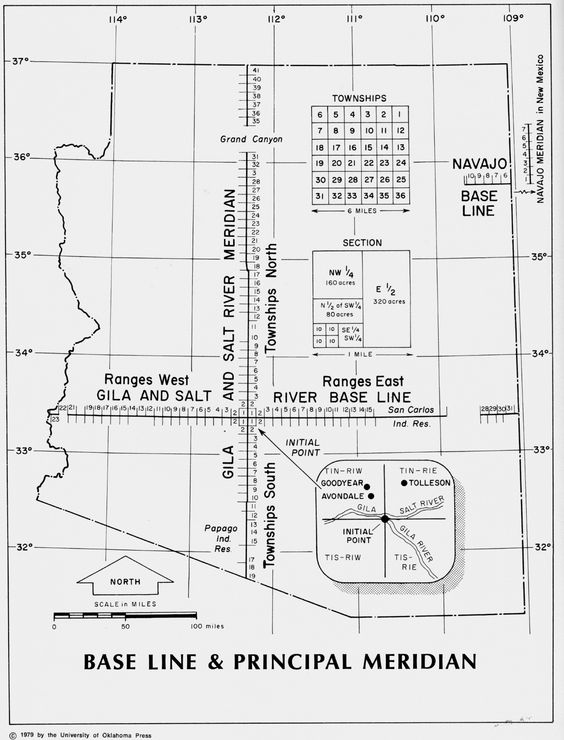

In 1785, the United States adopted the Public Land Survey System to avoid the problems of metes and bounds. From a designated zero point, a baseline extends east-west; a meridian stretches north-south. The two axes create a grid, where any point can be mathematically described. When the system was first used in the U.S., many townships declared their own zero point. On a survey map, Ohio is still a Tetris board of small, contrasting colored blocks.

Later, entire territories were surveyed from a single zero point. The state of Arizona is a vast swath of yellow on PLSS maps, its 114,000 square miles gridded into townships, sections, quadrants, parcels, all defined by their distance from a single point of origin.

The first house I rented in Arizona was within the S/T/R (section, township, range) of 211N4E. There are 2,287 structures in 211N4E, according to the Maricopa County Assessor’s Office. The Assessor’s Parcel Number of the home was 124-70-040. This tells you exactly where it was. It can’t tell you that the front and back of the house were rented as two separate units. It won’t tell you which part of the house I occupied, and of course, it tells you nothing about the time I spent there, or the people I shared it with.

I left APN 124-70-040 to move in with the man I would later marry, each leaving our apartments for a new life at APN 124-62-071, a pink cinderblock house that friends called Candyland. There was an orange tree in the backyard heavy with disappointing oranges, baggy and tasteless.

After a year we moved together to Michigan, rented another house, yellow and violet. We purchased a gray house together, on a lot so small that if the house ever burns down, we will need a variance from the city to rebuild. I go about my days assuming that if we ever need it, the variance will be granted. Really, I go through my days assuming that my house will not burn down.

Arizona’s point of origin is now a small tourist attraction called Monument Hill, where a mosaic tile X marks the spot. Most of the NASCAR fans visiting the nearby Phoenix International Raceway do not take the time to visit the marker. That is not a dig at NASCAR fans: no one else takes the time to visit either. I didn’t, when I lived in Arizona. I didn’t know that Arizona had a point of origin, that Phoenix’s endless sprawl radiates from a knowable, visitable spot. A small plaque reads, “Dedicated to all land owners in Arizona by the Arizona Professional Land Surveyors / Originally set by A.B. Gray in 1851.” If you do not own property, this marker is not for you. The PLSS turned thousands of square miles into square miles, land that could be measured and named and mapped. Because it could be mapped, it could be bought and sold.

Arizona’s point of origin is now a small tourist attraction called Monument Hill, where a mosaic tile X marks the spot. Most of the NASCAR fans visiting the nearby Phoenix International Raceway do not take the time to visit the marker. That is not a dig at NASCAR fans: no one else takes the time to visit either. I didn’t, when I lived in Arizona. I didn’t know that Arizona had a point of origin, that Phoenix’s endless sprawl radiates from a knowable, visitable spot. A small plaque reads, “Dedicated to all land owners in Arizona by the Arizona Professional Land Surveyors / Originally set by A.B. Gray in 1851.” If you do not own property, this marker is not for you. The PLSS turned thousands of square miles into square miles, land that could be measured and named and mapped. Because it could be mapped, it could be bought and sold.

Arizona’s north-south axis is called the Gila and Salt River Meridian. When the state was first surveyed, both rivers ran year-round. But the maps that made it possible to claim land eventually also made it possible to claim water. Beginning in the 1880s, the diversion of water upstream strangled tribal farming and starved Native Americans, who had been living in the area for thousands of years.

The river meridian laid the path for the modern Avondale Boulevard/115th Avenue. The east-west axis is what became Baseline Road.

Both places I lived in Tempe were just north of Baseline. I drove it often, both as means and destination. It’s where the Target was, my bank. Fry’s Electronics, Mexican and Chinese restaurants, drugstores, car repair shops, miles of fast food and indifferent retail. Nowhere you particularly want to be, but plenty of places you end up because you need something: batteries, Tylenol, a cheeseburger. Apartment complexes line stretches of Baseline behind tall privacy walls, plus a housing development called The Lakes, where streets named Whalers Way, Steamboat Bend, and Jolly Roger snake between canals cut through the desert. All this is within the town of Tempe alone, part of the greater Phoenix conglomeration. Baseline Road runs through it all, from Apache Junction in the east to 547th Ave in Tonopah to the west. In places, it breaks off and restarts, accommodating natural obstructions; occasionally it changes names. But for over 100 miles it is identifiably Baseline Road. The PLSS reserves the Baseline name for any future road at the same latitude, so theoretically, the street could eventually cross the entire state of Arizona.

The year we moved into APN 124-62-071, the city was beset by serial killers. The Arizona Republic later dubbed it the “Summer of Fear,” when the Baseline Killer and the Serial Shooter murdered a collective seventeen people and attacked dozens more. The Serial Shooter turned out to be multiple shooters, friends, who aimed at living targets from their car like a live action video game. They started with dogs and horses. Then a man on a bicycle bringing candles to a family who had lost electricity. A man asleep on a bus stop bench. The murders were spread across the valley, so that nowhere felt entirely safe. When one of the suspects was arrested, he held a trash bag with a shotgun shell and a map of the killings.

When Phoenix’s downtown grid was established in 1870, the east-west roads were named after early American presidents. The north-south streets were named after Native American tribes. Jackson Street intersected Mojave, Papago, Yuma, Cocopah, Hualpai, Yavapai. Early Phoenix property owners could purchase land at the intersection of a proponent of genocide and those who survived it.

In 1910, it was decided that the growing city would be easier to navigate with numbered, rather than named, streets. The mayor and city council decided to keep the presidents; the tribal names were erased, replaced with numbers.

The Baseline Killer was first known as the Baseline Rapist, before police realized that the same man was killing women who resisted his demands. Nine murders and at least 33 assaults. The break in the case came when two sisters were abducted while walking home from a park. One was six months pregnant, and the Baseline Killer held a gun between her legs and told her to beg for her life and her unborn child’s. For unknown reasons, he later let them go. They carried on them enough physical evidence to identify, arrest, and convict a suspect, even though one of the sisters later in court mistakenly identified the man’s attorney as her attacker.

Some English parishes used to observe a yearly “beating of the bounds,” described thus by William Barnes in the 1832 edition of Hone’s Year Book: "A Perambulation, or, as it might be more correctly called, a circumambulation, is the custom of going round the boundaries of a manor or parish, with witnesses, to determine and preserve recollection of its extent, and to see that no encroachments have been made upon it, and that the landmarks have not been taken away.

… In order that they may not forget the lines and marks of separation [the boys of the parish] take pains at almost every turning. For instance, if the boundary be a stream, one of the boys is tossed into it; if a broad ditch, the boys are offered money to jump over it, in which they, of course, fail, and pitch into the mud, where they stick as firmly as if they had been rooted there for the season ; if a hedge, a sapling is cut out of it and used in afflicting that part of their bodies upon which they rest in the posture between standing and lying; if a wall, they are to have a race on the top of it, when, in trying to pass each other, they fall over on each side, some descending, perhaps, into the still stygian waters of a ditch, and others thrusting the 'human face divine ' into a bed of nettles ; if the boundary be a sunny bank, they sit down upon it and get a treat of beer and bread and cheese, and, perhaps, a glass of spirits.”

The custom dates at least to Anglo-Saxon times, and may have been derived from the earlier Roman festival Terminalia. The ritual is largely extinct, geographical boundaries no longer dependent on fallible, human memory.

When I put our engagement on Facebook, I unleashed a year’s worth of ads for bridesmaid dresses. One year after I changed my status to married, the algorithms began to show me ads for infertility treatments. That is how long Facebook thinks a woman in her 30s should be married but not pregnant: exactly one year.

Later than Facebook thought we should, we decided we would like to start trying for a child. Once the decision was made, what we really wanted was for a child to arrive exactly nine months later. We didn’t at first believe or admit that this was what we wanted, but our first months of failure frightened us beyond reason. We were used to our bodies obeying us, more or less. Now there was something new we wanted, and for months it didn’t happen. We had had the sunny banks of the English parish boys, the beer and bread and cheese; we had not taken pains at almost every turning. Had we then failed to earn or learn something essential, about the boundaries of our life together?

Uses of baselines:

- in surveying, a line between two points of the earth’s surface and the direction and distance between them

- in configuration management, the process of managing change

- in seas, the starting point for delimiting a coastal state’s maritime zones

- in typography, the line upon which most letters “sit” and below which descenders extend

- in budgeting, an estimate of budget expected during a fiscal year

- in interferometry, the length of an astronomical interferometer

- in pharmacology, a person’s state of mind or being, in the absence of drugs

- in medicine, information found at the beginning of a study

Eight years after we moved away from Arizona, my husband and I flew back to Phoenix. Minutes after leaving the airport we saw an electronic freeway sign asking for tips on an active serial shooter. We laughed. I wondered if what I felt was nostalgia, if nostalgia could be inspired by serial shooters. But beneath the eye-rolling, there was also fear. From the passenger seat, I looked up the latest shooter on my phone: no one had died yet, but bullets had struck vehicles driving the same stretch of highway we were on. A CBS 5 story mentioned, “Longtime residents still remember a string of random shootings that terrorized Phoenix a decade ago.”

“If we’d stayed,” I told my husband, “we’d be ‘longtime’ residents by now.” At first it felt silly. But no, I realized—ten years is a long time.

All that time together, and it had taken us this long to decide we wanted a child? Why had we put so much distance between the points of our life together, and why had we assumed we got to choose where those points would be fixed?

At the Arizona State University art museum, a video art installation showed a loop of footage taken out the window of a car driving the entire length of Baseline Road. I never watched the whole thing, not even close: even sped up, far faster than a car could move along the heavily trafficked road, the video run time was 120 minutes. I would watch for a little while, the endless strip malls giving way to dusty empty lots and industrial agriculture. This failure of imagination is mine, not the artist’s, but all I remember feeling while watching this video was surprise and resignation: that Baseline Road was so very long, and that it was all so, so boring. It was not a road that easily prompted one to think about its origins, its destinations, or about much of anything. Until the crime spree, and then its name made people think of death.

When I did become pregnant, my nose bled off-and-on for months. I asked my doctor, an unflappable older man, if my nosebleed was normal. I was always asking if something was normal, but I didn’t always entirely care about the answer; as long as I wasn’t falling apart completely, the pregnancy still felt like a gift, a relief, a lucky break. A bullet dodged.

“Does the bleeding stop each time?” he asked.

“Eventually, yes.”

“Then let’s say it’s normal for you.”

Also, my ribcage and right hand had gone numb. Was that normal? “Just be careful around hot stoves,” he advised.

I liked this doctor a lot. I knew that if I ever saw him truly concerned, I would probably be about to die.

The summer of 2016, another Phoenix serial killer. The seven victims—men, women, a 12 year old girl—shot outside their own homes, seemingly at random. Unlike the 2006 shootings, these are concentrated in a single Phoenix neighborhood, Maryvale, described variously in news reports as “low-income,” “working class,” or simply “poor.” This gives everyone who doesn’t live in Maryvale a possibly false sense of security. As of this writing, the killer is still at large.

As my husband drove the rental car through Phoenix, I unfolded the map of Arizona that had come with the car. Noodles of road, splotches of mint-green national forestland, narrow black county markers: the kind of map no one really uses anymore, not for navigation. Red drops suddenly appeared over South Phoenix. It took me a moment to figure out what was happening, where the red was coming from. My nose. The dry air. I wadded up tissues, held them between me and the map, my outfit, the upholstery. I soaked a fistful. Hello, blood. Hello, baby. Hello, Arizona. For a moment I felt like I should keep the bloody map, a souvenir of something. Of course I didn’t.

Ninth months later we were out for an evening walk, my husband and I, our baby in the stroller. I said that I was reading about meridians and baselines. I described the zero point by the International Raceway in Avondale. How the places we’d lived could be named with numbers. How the road we took to run errands was named after a line the length of the state. How the serial killer that haunted our last year there had, it turned out, been named after something ambitious and elegant.

"Do you think all that’s interesting?" I asked, a loaded question. Anything can be interesting, so what I was really asking was whether I could pull off writing about them.

"What would you be writing about?" he asked. "How life is like a map?"

I couldn’t tell if he was joking. "Of course not," I said, wanting to acknowledge the potential for cliché. "That’s not what I’m saying at all."

It is, of course, and it isn’t. I used to romanticize the word platting because I didn’t really understand what it meant. Plus it looked mysterious, one letter off from other, more familiar words—planting, plating, plotting, plaiting. Turns out it’s synonymous with plain old “mapping,” and a plat map is simply one that shows “divisions of the land.” The word can also be synonymous with plaiting. One could plot a plat map. Plait the pages. Plant a survey marker, plot a grid, pretend you know what landscape those lines will cover. Plait a child’s hair into a braid, plant a ribbon around it and send her down the road, hoping she arrives at her destination, pretending you can envision what that destination will look like. The contiguous baseline is an abstraction, an illusion of the system, of the page.

Before our trip together, I’d returned once to Arizona by myself. On the drive west I had the worst nightmare I’ve ever had. I was very pregnant in this dream, which I thought was bad enough, which was, for many years of my life, nearly the worst dream I thought I could have.

But also the world was ending, an unnamed contagion sweeping the planet. In my dream, a prophet insisted he had a cure, which he would explain only on television. The world over, everyone gathered to watch. Instead of offering a plan, the man stared into the camera and began cutting his body open, and as he bled we understood that he was a crazed liar, that there was no cure and no hope.

This was the most real-feeling dream I have ever experienced, and the morning I woke up in a hotel room in Nebraska and realized it wasn’t true counts as one of the best mornings of my life. For hours the crops and sky slid by, made beautiful with gratitude: I wasn’t about to die alongside everyone I’d ever loved. I was not responsible for a child whom I would not be able to protect. I held onto that feeling through as many gas stations and rest stops as I could, until the miles ground it down. Here was me, the day, the endless highway, no more special than they ever were. Which is to say, not at all; which is to say, endlessly.

For more information about this piece, see this issue’s legend.

Caitlin Horrocks is author of the story collection This Is Not Your City. Her stories and essays appear in The New Yorker, The Best American Short Stories, The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories, and other journals and anthologies. She is fiction editor of The Kenyon Review and teaches at Grand Valley State University and in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. She is currently working on a novel and a second story collection, both forthcoming from Little, Brown.

56°40′08″N 5°01′34″W

Many years ago, I ended up on one of those gloomy bus tours where they drop you off at famous places for totally insufficient lengths of time, then herd you back onto the bus so you can be driven to another famous place for another totally insufficient length of time. And so on for days and days. This is the place whose beauty brought me closest to refusing to reboard the bus, to run screaming off into the countryside instead. At the time, I consoled myself with the thought that I would return someday on my own. I haven’t yet. My white whale.