Legend

Prisons

Prisons are austere structures, made mostly of metal and rock. They are a grid made of other grids—the cell within the block within larger, less literal grids. As Michel Foucault observes, the prison cell is an heir of the monastic cell, an ascetic space of reflection and transcendence, a space of stark binaries: good and evil, right and wrong, innocent and guilty, inside and out. This is because prisons, while nominally about rehabilitation and reentry, or at least some sense of justice, are really about segregation. They physically separate minorities from majorities—along racial, sexual, socioeconomic, ideological, and countless other lines—on behalf of majorities and their interest in preserving their status as such. This is why, within five years of being released (if at all), about three-quarters of the 2.3 million prisoners in the United States will be arrested again. The center has no space for what exists beyond its periphery.

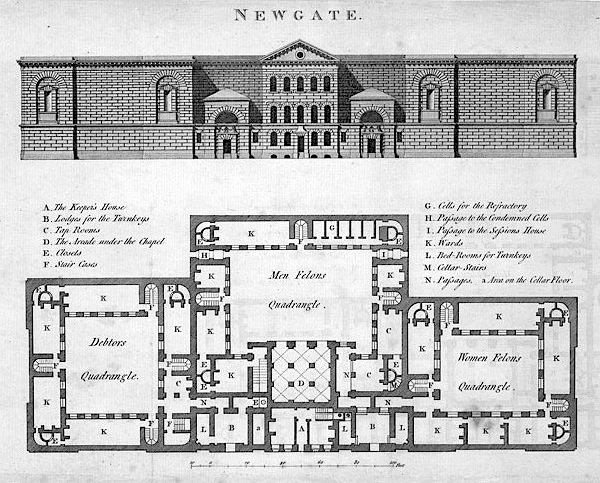

This black-and-white logic of the prison is evident in its maps. Informational, diagrammatic, instructional, devoid of color—maps of prisons present themselves as objective and authoritative as the spaces they represent, and they do similar work: they remove people from the picture, turning the prison into a matter of engineering, an abstraction. If they offer any flourish it’s in their symmetries, but even these are geometric, rigid—efficiency and order as aesthetic. But not accessibility. We had a hard time even finding maps of prisons that hadn’t been decommissioned in a previous century and thus safely contained in the past and rebranded as a curiosity: Alcatraz, The Panopticon, the “squirrel cages” of the Pottawattamie County Jailhouse. If prisons are to effectively divert our gaze, their maps must be used for construction, not deconstruction.

This black-and-white logic of the prison is evident in its maps. Informational, diagrammatic, instructional, devoid of color—maps of prisons present themselves as objective and authoritative as the spaces they represent, and they do similar work: they remove people from the picture, turning the prison into a matter of engineering, an abstraction. If they offer any flourish it’s in their symmetries, but even these are geometric, rigid—efficiency and order as aesthetic. But not accessibility. We had a hard time even finding maps of prisons that hadn’t been decommissioned in a previous century and thus safely contained in the past and rebranded as a curiosity: Alcatraz, The Panopticon, the “squirrel cages” of the Pottawattamie County Jailhouse. If prisons are to effectively divert our gaze, their maps must be used for construction, not deconstruction.

All of which makes responding to this kind of map all the more challenging. How do you inspect what rejects inspection? Our contributors found that, for such a rigid space, prisons are surprisingly adaptive and frighteningly omnipresent. The titular palace of Brian Evenson’s story is really a prison and was first a hospital, which might be another kind of prison itself. Noah Warren recognizes the American imagination as an especially pervasive, stalking prison. Megan Giddings writes about the everyday enclosure of racism, even in the most “well-meaning” circumstances. Jordan Jacks manages to construct a prison out of an island of inner tubes at a German-themed water park. Don’t forget that the device you’re reading this on is also a means of surveillance.

So prisons can be found everywhere and in everything, but that doesn’t mean they are inescapable. It’s their very reach and plasticity that pokes holes in the boundaries they vow to uphold. Sequestered in solitary confinement, prisoners access the past, the future, alternative versions of themselves, or the “flashing fallopian neon tendrils” of the prisoner’s cinema. Given the opportunity to describe their cell, writers from Allegheny County Jail’s Words Without Walls and the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop see an office, a revolving door, a family photo, the royal buttock of a fat king, rugs made from towels, dark matter, previous occupants, an entire country, disappointment, the vastness of the cosmos, and an alien giving the finger. In this great multiplicity, they even see Spongebob.

This is not to promote another majority’s fantasy—that the material realities of the prison can be overcome with imagination and empathy and humanity and whatever else art has to offer—but simply to acknowledge the complexities and contradictions of the subject, to see a prison for what it is, to resist its attempts to escape into the inflexible logic of its own map.

-Nick Greer & Thomas Mira y Lopez

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Brian Evenson’s “Palace” is narrated by the architect of a hospital-turned-prison, and though the narrator is never named, he can be read as a specter of Parisian architect Bernard Poyet, whose Projet pour l'Hôtel-Dieu serves as blueprint for the story. In 1785, Poyet was hired by the Académie des Sciences to redesign the hospital, which had been partially destroyed in a fire in 1772 and had become so crowded in the decade following that by the time Poyet had been hired, it slept three to most of its 1,200 beds. Inspired by the Colosseum of Rome, Poyet proposed a circular building of sixteen wards, circumscribing an interior courtyard centered on a chapel. The Académie rejected the radial design on the grounds that it was “not conducive to the renewal of vitiated air.” The winning design, for whatever it did for air quality, couldn’t solve for bureaucratic inefficiencies that survived the Revolution, provoking Poyet to renew his proposal in his 1807. Poyet died in December 1824, “not without having had the pleasure of reading [his own] obituaries” after the Gazette de France prematurely announced his death earlier that year.

Brian Evenson’s “Palace” is narrated by the architect of a hospital-turned-prison, and though the narrator is never named, he can be read as a specter of Parisian architect Bernard Poyet, whose Projet pour l'Hôtel-Dieu serves as blueprint for the story. In 1785, Poyet was hired by the Académie des Sciences to redesign the hospital, which had been partially destroyed in a fire in 1772 and had become so crowded in the decade following that by the time Poyet had been hired, it slept three to most of its 1,200 beds. Inspired by the Colosseum of Rome, Poyet proposed a circular building of sixteen wards, circumscribing an interior courtyard centered on a chapel. The Académie rejected the radial design on the grounds that it was “not conducive to the renewal of vitiated air.” The winning design, for whatever it did for air quality, couldn’t solve for bureaucratic inefficiencies that survived the Revolution, provoking Poyet to renew his proposal in his 1807. Poyet died in December 1824, “not without having had the pleasure of reading [his own] obituaries” after the Gazette de France prematurely announced his death earlier that year.

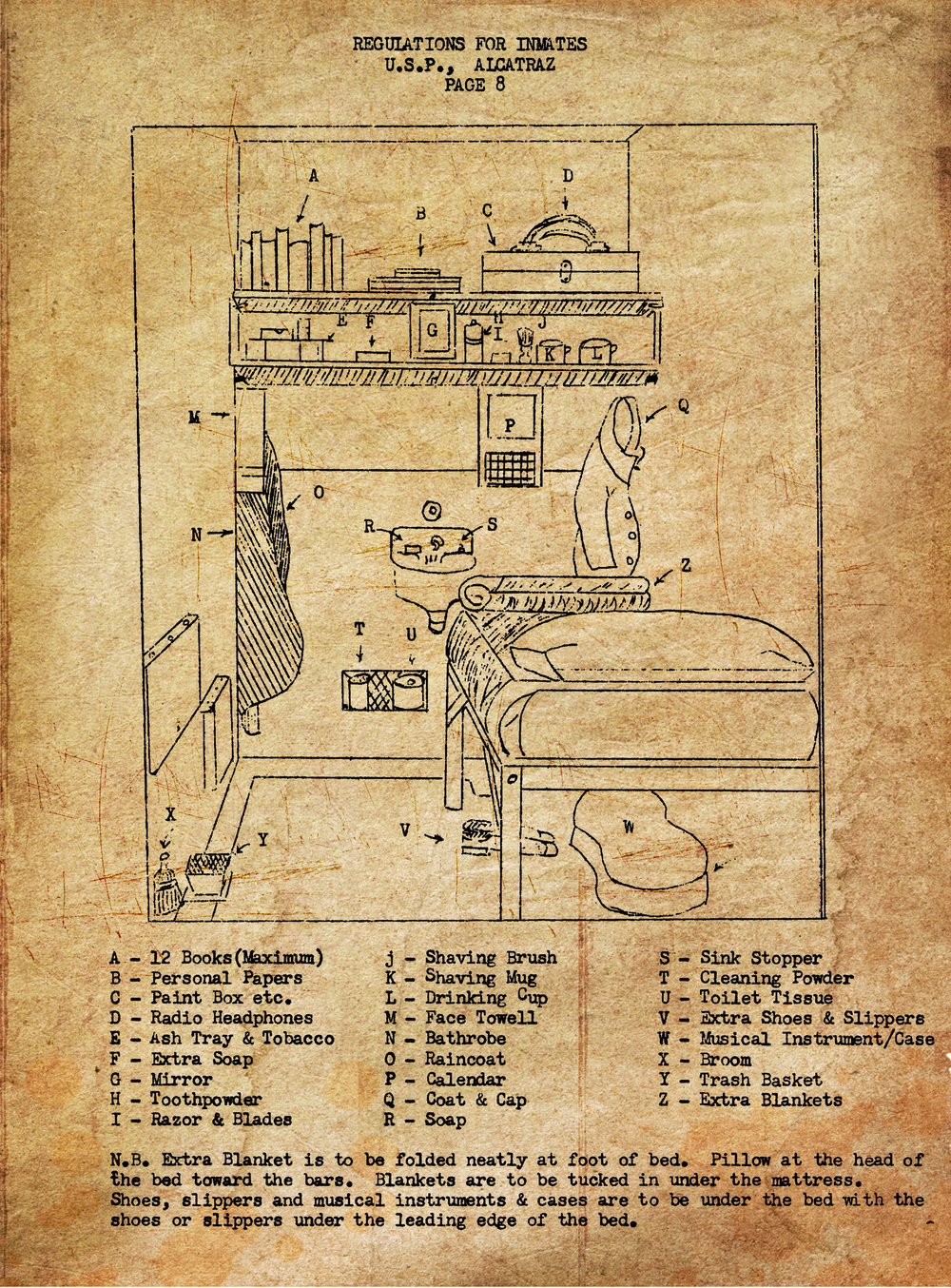

Elisa Gabbert’s “A Bedroom in Alcatraz” considers the curious perspective in a diagram found in Paul J. Madigan’s 1956 pamphlet Institution Rules & Regulations, United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz, California. It’s not just that the diagram rotates away from the typical overhead view of a map, but that it bears an uncanny resemblance to Vincent Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles. Van Gogh completed the third iteration of the painting in September of 1889, between his extended stays at the Saint-Paul Asylum in Saint-Rémy. During his time there, Van Gogh focused on imitations of other artists’ paintings, including Gustav Doré’s Newgate, Exercise Yard (1872), in which prisoners walk in a circle. In a letter to his brother, dated February 1890, Van Gogh writes, “J'ai essayé de copier les buveurs de Daumier et le bagne de Doré, c'est très-difficile.” The artist behind the Alcatraz diagram makes no mention of attempting to copy Van Gogh, the difficulty of doing so, or even their own name.

Elisa Gabbert’s “A Bedroom in Alcatraz” considers the curious perspective in a diagram found in Paul J. Madigan’s 1956 pamphlet Institution Rules & Regulations, United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz, California. It’s not just that the diagram rotates away from the typical overhead view of a map, but that it bears an uncanny resemblance to Vincent Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles. Van Gogh completed the third iteration of the painting in September of 1889, between his extended stays at the Saint-Paul Asylum in Saint-Rémy. During his time there, Van Gogh focused on imitations of other artists’ paintings, including Gustav Doré’s Newgate, Exercise Yard (1872), in which prisoners walk in a circle. In a letter to his brother, dated February 1890, Van Gogh writes, “J'ai essayé de copier les buveurs de Daumier et le bagne de Doré, c'est très-difficile.” The artist behind the Alcatraz diagram makes no mention of attempting to copy Van Gogh, the difficulty of doing so, or even their own name.

Megan Giddings’ “You Are the Shackles, You Are the Bonds” maps a plan of Millbank Prison, a nineteenth century facility in central London. The prison housed men and women awaiting relocation to Australia, although the grounds were originally intended to serve as the site of Jeremy Bentham’s famed Panopticon. Henry James describes the building unfavorably, as a structure “lying there, sprawling over the neighborhood with brown, bare, windowless walls, truncated pinnacles and a character unspeakably sad and stern.” So much for Henry James. With its six pentagrams seen from a bird’s eye, the design for the prison resembles an unusually squat wood lily or six coffins arrayed around a bull’s eye. Now the Tate Britain gallery sits where Millbank Prison once did, a different kind of entombment.

Megan Giddings’ “You Are the Shackles, You Are the Bonds” maps a plan of Millbank Prison, a nineteenth century facility in central London. The prison housed men and women awaiting relocation to Australia, although the grounds were originally intended to serve as the site of Jeremy Bentham’s famed Panopticon. Henry James describes the building unfavorably, as a structure “lying there, sprawling over the neighborhood with brown, bare, windowless walls, truncated pinnacles and a character unspeakably sad and stern.” So much for Henry James. With its six pentagrams seen from a bird’s eye, the design for the prison resembles an unusually squat wood lily or six coffins arrayed around a bull’s eye. Now the Tate Britain gallery sits where Millbank Prison once did, a different kind of entombment.

Jordan Jacks’ “Elba” reimagines the island of Napoleon’s exile as a stack of inner tubes in a moribund Texas water park. The map depicted was drawn up almost a century after Napoleon’s exile, as part of the 3rd Military Mapping of Austria-Hungary, a survey done in anticipation of the first World War. One of the editors of this journal was surprised to learn that Elba is not in fact a part of France, but Italy, specifically the region of Tuscany. While Elba is typically thought of as a place of exile and thus isolation, it has recently served as an important way station in the migration of refugees from North Africa. Its population has swelled to such a degree that, according to The New York Times, Tuscany has granted the island “a reprieve from the mandatory redistribution system”. For his part, Napoleon supposedly exhibited munificence to refugees during his time on the island. According to The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte by Sir Walter Scott, the emperor once offered a freshly arrived Italian commandant a 1200 franc stipend despite being sorely in need of funds himself.

Jordan Jacks’ “Elba” reimagines the island of Napoleon’s exile as a stack of inner tubes in a moribund Texas water park. The map depicted was drawn up almost a century after Napoleon’s exile, as part of the 3rd Military Mapping of Austria-Hungary, a survey done in anticipation of the first World War. One of the editors of this journal was surprised to learn that Elba is not in fact a part of France, but Italy, specifically the region of Tuscany. While Elba is typically thought of as a place of exile and thus isolation, it has recently served as an important way station in the migration of refugees from North Africa. Its population has swelled to such a degree that, according to The New York Times, Tuscany has granted the island “a reprieve from the mandatory redistribution system”. For his part, Napoleon supposedly exhibited munificence to refugees during his time on the island. According to The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte by Sir Walter Scott, the emperor once offered a freshly arrived Italian commandant a 1200 franc stipend despite being sorely in need of funds himself.

M Kitchell’s “First Movement Toward a Crucifiction” takes place within a special kind of prison as per U.S. Patent No. 244,358, dated July 12, 1881, which outlines a jail comprising “a circular cell structure of considerable size...divided into several cells capable of being rotated” and the technology for operating this rotary system. This novel structure makes possible equally novel means of surveillance: “the idea of keeping the cell structure in continual rotation during the night, or at any other time when the prisoners cannot be conveniently watched, and thus prevent even an attempt on their part to cut their way out at such times.” Lazy, impersonal administration is actually one of the primary goals of the design, which notes the rotary structure means “prisoners can be controlled without the necessity of personal contact between them and the jailer or guard.” Personal contact did become necessary though when inmates’ limbs were crushed or lopped off by the rotating bars. To avoid these accidents, most of the few rotary prisons that were built welded their gears shut and refitted the cells to permit traditional access. The longest operating of these prisons, the “squirrel cages” of the Pottawattamie County Jailhouse was decommissioned in 1969 and converted to a museum.

M Kitchell’s “First Movement Toward a Crucifiction” takes place within a special kind of prison as per U.S. Patent No. 244,358, dated July 12, 1881, which outlines a jail comprising “a circular cell structure of considerable size...divided into several cells capable of being rotated” and the technology for operating this rotary system. This novel structure makes possible equally novel means of surveillance: “the idea of keeping the cell structure in continual rotation during the night, or at any other time when the prisoners cannot be conveniently watched, and thus prevent even an attempt on their part to cut their way out at such times.” Lazy, impersonal administration is actually one of the primary goals of the design, which notes the rotary structure means “prisoners can be controlled without the necessity of personal contact between them and the jailer or guard.” Personal contact did become necessary though when inmates’ limbs were crushed or lopped off by the rotating bars. To avoid these accidents, most of the few rotary prisons that were built welded their gears shut and refitted the cells to permit traditional access. The longest operating of these prisons, the “squirrel cages” of the Pottawattamie County Jailhouse was decommissioned in 1969 and converted to a museum.

Caits Meissner’s “Trapping” was inspired by Frank Alejandrez’s drawing of his windowless 11’7″ x 7’7″ “secure housing unit” (SHU) at the Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, California. Pelican Bay’s 1,500 SHU inhabitants spend 22.5 hours per day in these units where they will stay for an average of 7.5 years, most often on the grounds that they are validated gang members. According to Mother Jones, this validation, which requires three pieces of evidence, one of which must be a “direct link,” is most often achieved through reading materials—including Karl Marx, George Jackson, Sun Tzu, and Robert Greene—or iconography: a cup bearing a picture of a dragon linked to the Black Guerrilla Family; a drawing of a huelga bird, which is affiliated with the Nuestra Familia, the gang Alejandrez is a “validated” member of, according to a Geocities site managed by Gate City Publishing.

Caits Meissner’s “Trapping” was inspired by Frank Alejandrez’s drawing of his windowless 11’7″ x 7’7″ “secure housing unit” (SHU) at the Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, California. Pelican Bay’s 1,500 SHU inhabitants spend 22.5 hours per day in these units where they will stay for an average of 7.5 years, most often on the grounds that they are validated gang members. According to Mother Jones, this validation, which requires three pieces of evidence, one of which must be a “direct link,” is most often achieved through reading materials—including Karl Marx, George Jackson, Sun Tzu, and Robert Greene—or iconography: a cup bearing a picture of a dragon linked to the Black Guerrilla Family; a drawing of a huelga bird, which is affiliated with the Nuestra Familia, the gang Alejandrez is a “validated” member of, according to a Geocities site managed by Gate City Publishing.

Jericho Parms’ “Four Walls, A Chamber” maps a 1936 survey of Kilmainham Prison in Dublin, Ireland. The survey depicts all four floors of the gaol: basement, ground, first, and second. The map you see here is of the basement. The gaol has almost 20,000 reviews on Trip Advisor, with seventy-one percent of visitors rating it excellent. The most recent review praises the tour as “great value and not too long, which pleased the teenagers!” Nearly 400,000 people visited Kilmainham in 2016, two and two-thirds the number of prisoners incarcerated there from 1796 to 1924.

Jericho Parms’ “Four Walls, A Chamber” maps a 1936 survey of Kilmainham Prison in Dublin, Ireland. The survey depicts all four floors of the gaol: basement, ground, first, and second. The map you see here is of the basement. The gaol has almost 20,000 reviews on Trip Advisor, with seventy-one percent of visitors rating it excellent. The most recent review praises the tour as “great value and not too long, which pleased the teenagers!” Nearly 400,000 people visited Kilmainham in 2016, two and two-thirds the number of prisoners incarcerated there from 1796 to 1924.

Shaelyn Smith’s “Salt of the Earth” maps the confinement of women, both literal and metaphorical, through a tapestry of cultural, political, and personal examples. One such example is an actual tapestry, The Unicorn in Captivity, prized possession of The Cloisters in New York. In a wide-ranging Talk of the Town interview in The New Yorker, the actor Aubrey Plaza and director Jeff Baena visit the tapestry at the Cloisters, where, among other topics, they discuss David Bowie’s dabbling in the occult during his two year diet of milk and bell peppers. If one travels to the Cloisters by subway, one exits at the 190th street station. The station is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is one of the few that not only requires one to exit by elevator but also employs elevator operators. As one rides the elevator, which is of course windowless, the operator will glance around the tight, confined space and nod hello to the regulars.

Shaelyn Smith’s “Salt of the Earth” maps the confinement of women, both literal and metaphorical, through a tapestry of cultural, political, and personal examples. One such example is an actual tapestry, The Unicorn in Captivity, prized possession of The Cloisters in New York. In a wide-ranging Talk of the Town interview in The New Yorker, the actor Aubrey Plaza and director Jeff Baena visit the tapestry at the Cloisters, where, among other topics, they discuss David Bowie’s dabbling in the occult during his two year diet of milk and bell peppers. If one travels to the Cloisters by subway, one exits at the 190th street station. The station is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is one of the few that not only requires one to exit by elevator but also employs elevator operators. As one rides the elevator, which is of course windowless, the operator will glance around the tight, confined space and nod hello to the regulars.

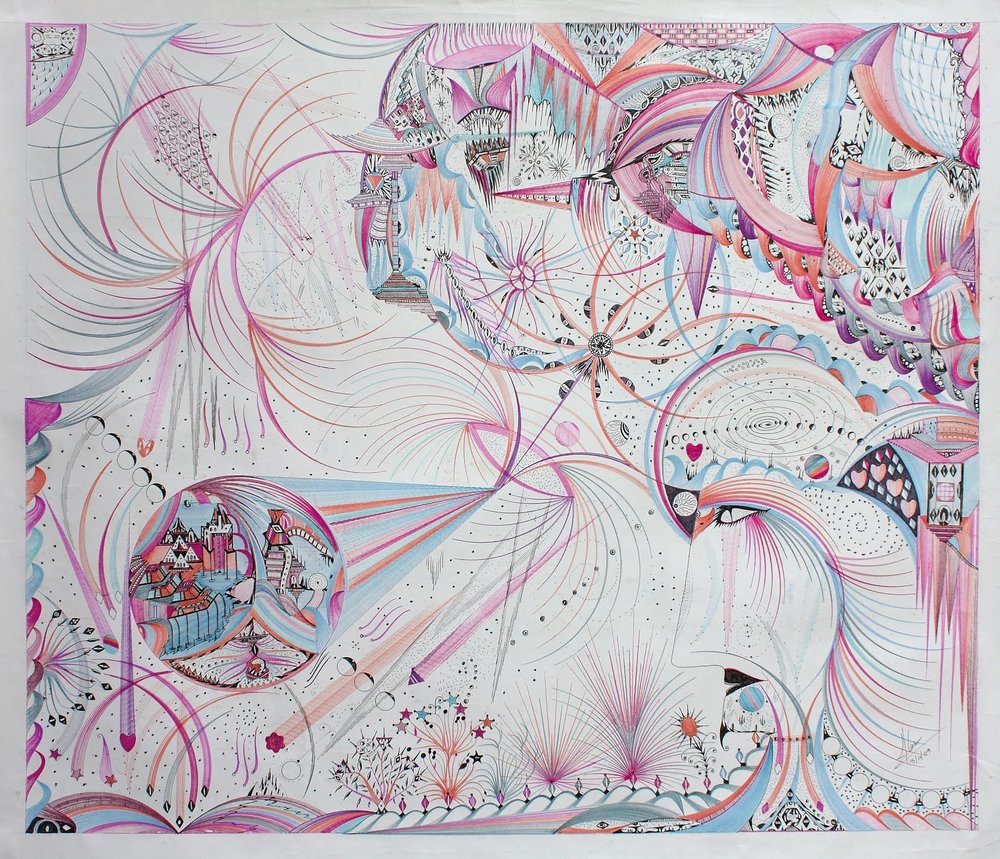

Garett Strickland’s “CELL FILM” is a fictional film of another fictional film, the prisoner’s cinema, a phenomenon in which someone confined to prolonged darkness will begin to see visual hallucinations known as phosphenes (from Greek, phōs ‘light’ + phainein ‘to show’) though phosphenes can also be induced by putting pressure on the eye, which stimulates the retina. In a 1988 paper, two archeologists affiliated with the Rock Art Research Unit at the University of Witwatersrand posit that the non-figurative petroglyphs found at rock sites in California and South Africa are renderings of these visuals produced by shamans experiencing sensory deprivation in the innermost “sanctuaries” of the local cave systems. Modern psychonauts have described these visions as more exogeneous, encounters with extraterrestrial and interdimensional beings. After an avistamiento of one of these beings, Uruguayan artist Alexandro Garcia began painting to channel their energy, resulting in works like Mirada de amor (2009), which informs Strickland’s piece.

Garett Strickland’s “CELL FILM” is a fictional film of another fictional film, the prisoner’s cinema, a phenomenon in which someone confined to prolonged darkness will begin to see visual hallucinations known as phosphenes (from Greek, phōs ‘light’ + phainein ‘to show’) though phosphenes can also be induced by putting pressure on the eye, which stimulates the retina. In a 1988 paper, two archeologists affiliated with the Rock Art Research Unit at the University of Witwatersrand posit that the non-figurative petroglyphs found at rock sites in California and South Africa are renderings of these visuals produced by shamans experiencing sensory deprivation in the innermost “sanctuaries” of the local cave systems. Modern psychonauts have described these visions as more exogeneous, encounters with extraterrestrial and interdimensional beings. After an avistamiento of one of these beings, Uruguayan artist Alexandro Garcia began painting to channel their energy, resulting in works like Mirada de amor (2009), which informs Strickland’s piece.

Noah Warren’s “Autarky” is paired with a map of “Jamaica, Cuba, and Porto Rico” published in 1855 as part of George W. Colton’s Atlas Of The World, Illustrating Physical And Political Geography. At that time, Cuba was a colonial territory of the Spanish Empire, but with Spanish fortunes on the wane and a slave uprising in Matanzas, there was a scare among competing interests that Cuba would “Africanize.” Wealthy Cubans tried to enlist the United States Army to keep the peace. The US had designs on the island and its resources, but Southern states, fearful that Africanization would lead to a contagious spread of abolition and free—as opposed to slave—labor, linked up with Cuban exiles to protest American amnesty. Though the British Empire had historically argued against slave labor in Cuba to thwart Spanish economic growth, they now feared the United States enough that they flip-flopped, publically endorsing Spanish rule while creeping towards abolition behind closed doors, working with the (conveniently?) recently appointed Captain General Juan M. de la Pezuela to establish a slave registry.

Noah Warren’s “Autarky” is paired with a map of “Jamaica, Cuba, and Porto Rico” published in 1855 as part of George W. Colton’s Atlas Of The World, Illustrating Physical And Political Geography. At that time, Cuba was a colonial territory of the Spanish Empire, but with Spanish fortunes on the wane and a slave uprising in Matanzas, there was a scare among competing interests that Cuba would “Africanize.” Wealthy Cubans tried to enlist the United States Army to keep the peace. The US had designs on the island and its resources, but Southern states, fearful that Africanization would lead to a contagious spread of abolition and free—as opposed to slave—labor, linked up with Cuban exiles to protest American amnesty. Though the British Empire had historically argued against slave labor in Cuba to thwart Spanish economic growth, they now feared the United States enough that they flip-flopped, publically endorsing Spanish rule while creeping towards abolition behind closed doors, working with the (conveniently?) recently appointed Captain General Juan M. de la Pezuela to establish a slave registry.

At the height the panic, the United States considered intervening, either by purchasing the island or by seizing it, until a newly reappointed Captain General, José Gutiérrez de la Concha, “quieted much revolutionary fervor by abandoning the movement toward emancipation.” The final Captain General before the dissolution of Spanish rule, Ramón Blanco, was also one of the last Spanish Governor-Generals of the Philippines, a position that would go on to be held by five decades of Americans, including eventual president William Howard Taft.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.