When I was younger, I was able to imagine myself forward into time—as an artist foremost, but also as a body in the world. I was confident that the self I was already living into was indigenous, keyed, moreover, to my will, and I was confident that that ideal self would evolve according to my thought and experience. I would assemble myself—when my vast originality required alloys—only from those fragments of culture I had desired and assayed. I was so insecure. I smelled prestige and walked across Scotland, read Hume, chanted Wordsworth, and felt free—ahistorical. The contradictions I was able to contain were limitless.

Living only in imaginative prospect, I vitiated my selves before I arrived at them. The more I sought to mark my experiences as mine, the more they faded into type.

This is an essay about the American imagination and its global hegemony: an essay about prisons.

In October of 2011 I stand outside, if not near, the house my grandparents built in this once-hip Havana suburb. It isn’t huge, but a certain Frank Lloyd Wrightish cool makes it appear grander. One of its wings ventures off toward the lawn at an oblique angle, narrow windows stripe the walls, and its rotated roof tilts like a mortarboard. Around, an acre of lawn and palms languishes.

Many of the rambling old mansions of Miramar have been broken up into cramped apartments. But my family’s home was requisitioned by the Ministry of the Interior, the shadowy bureaucracy responsible for most of the police-state architecture, and so preserved. It is impossible to know what goes on behind the steel fence that now closes off the long driveway from the street—if anything. There is no guard because no one would dare. I linger at the gate, then walk down to the yacht club that features in so many family stories, now a shambolic concrete ruin.

A few days later Havana begins to make me unbearably sad. I travel to another city:

Weather

I sit at dinner

listening to the pigs snuff on the other side of the wall

and I look at my friend who is rolling

with laughter and a bright tear drips

from the point of her nose onto her spoon.

I look away. She tries to pull herself together

as we are served a course of fruit.

Do you believe in a permanent world.

The roads are pitted or torn away by storms. My route is roundabout: sometimes I cling to a bench in a shipping container that’s been punched with airholes and loaded on the back of a cargo truck; sometimes I’m on an airconditioned bus; sometimes (when my knee gives out in the Sierra Madre) bouncing on a mule.

In December 1960 my uncle Aníbal had been airlifted from Havana to Hartford under the auspices of Operation Peter Pan. The name was brilliant: it both resonated and dead-ended in the popular imagination. The Catholic Church, a vendor of virtue, looked to Disney for legibility. Castro as Hook. Children as white, innocent.  The name reinscribed imperial fantasy on an island that had long been appropriated by northamerican sin, northamerican amnesia, just as that fantasy was so violently shrugged off.

The name reinscribed imperial fantasy on an island that had long been appropriated by northamerican sin, northamerican amnesia, just as that fantasy was so violently shrugged off.

The general tone of media coverage toward the Revolution was—once Castro, rebuked by the US, turned to the USSR—an entirely proprietary outrage. Someone shat on our lawn. This amazingly flat narrative resulted, in the course of a year, in the Bay of Pigs.

I arrive in Santiago de Cuba on November 16th, 2011. My journal tells me I will leave on December 12th. I stay at the Hotel Libertad, in a dark room off the Plaza de Marte. The hallways are tiled and grand: they echo all night with unknowable conversations, loud and soft, with the quick clip of footsteps. On the weekends I am kept awake by a discotheque that throbs the roof. But I go up to the same roof every morning to read Kant at the tables sticky from the night before. A waiter mops around me. There is a tremendous view of the Sierra Madre across the white-and-green city. The mood is weary. I end up drinking a great deal of aged rum that month. I smoke a cigar every night to feel like a man smoking a cigar. Elaborate, cheap nativity displays go up in the Cathedral for Advent.

Plaza de Marte

Aguantar is the word I was looking at.

I was listening to the Youth Militia parade.

There was a time when I ate

And drank sweet juices without ever thinking that

This body could be a case for me.

I stood apart from the men that were rounding

The boulevard, playing trumpets at the park.

God knows I hate the heat, the satin masks.

I will never know who is the King of Spoons.

My friend, I can’t speak this idiom

Without compromise.

Without compromise. Look at the flashing machetes

Grating from their blazoned sheaths. Imagine what

We could do to the leg of an animal, in the night.

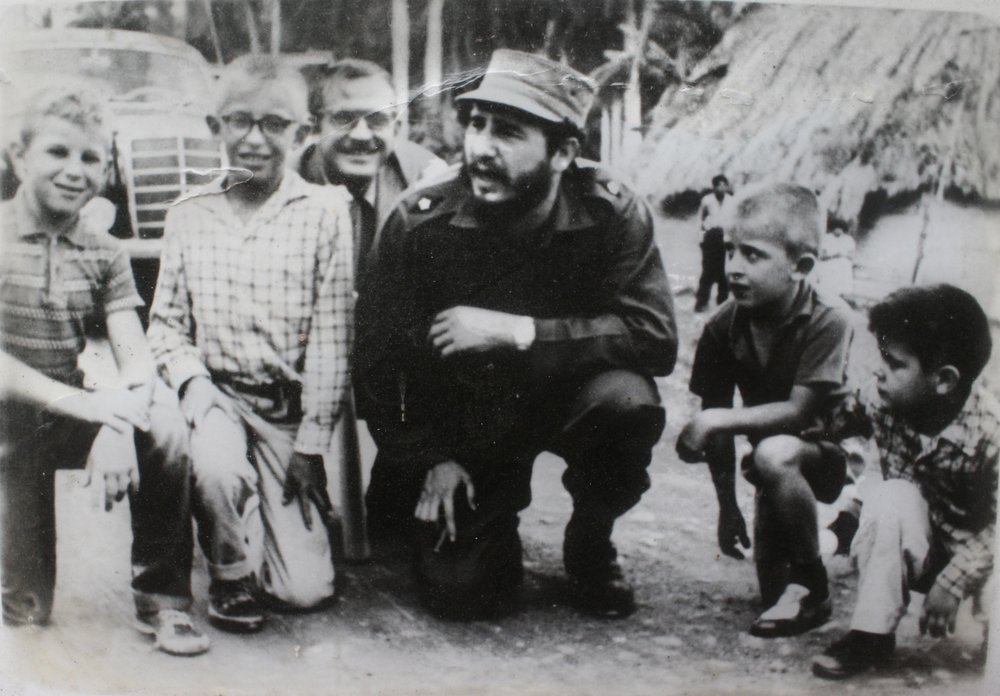

In Santiago I wander around the Bacardí museum, its tall humid galleries filled with propaganda, impassioned letters, blurred photographs, carnival museums, old rum barrels, bad landscape paintings, good portraits, cat mummies, fragments of Roman marbles, a shield, antique guns and Spanish uniforms. I feel haunted, white and guilt-ridden. The exhibition text takes frequent digs at the eponymous rum dynasts, who fled to Puerto Rico after the Revolution. When I walk through the streets, or sit at a table on the hotel balcony, I am frequently approached. Greeted with a warm “My friend…” — I wave him off. I hate the suspicion that begins to ride with me: what am I wanted for. I visit the mustard colored barracks upon which Castro led an idiotic assault in 1953, which has become yet another Revolutionary museum. Each time they renovate it, new bullets have to be shot in the plaster—to preserve the sense of threat.

In March 1961 my uncle Fernando followed his brother Aníbal; in May their parents managed to secure exit visas. They were accompanied by Enrique, age 10, my mother Ana-Maria, age 6, and my great-grandmother, age 75. Because they were allowed to leave the country with $100 between them, the women sewed jewels into their bras and panties.

One man I meet at a bar, whom I dislike, asks me, then begs me, to invite him to travel with me. I know everyone in Baracoa, he says. All the places. I know so many girls. We’ll have a really good time.

I feel more and more like a pale ghost, moving too lightly across the country. I experience double visions; I can convince myself that I am living in 1958. That I am my grandfather. When I wander the streets, people see me and they don’t. I see people and I don’t. I feel attached to the island, I recognize myself in the culture, but there are no palpable roots left, and when I try to explain the nature of my emotions, or even my parentage, I am met with blank looks. I stop explaining.

Baracoa is an enclave on the eastern tip of Cuba, walled off by a mountain range from the lowlands. Cacao, coconuts, and guava fill its sharp valleys. I heard it called “la boca del caimán:” the island as a toothy lizard.

The hotel, where the richer tourists stay, occupies the old colonial castle cum battery far above the town. I stay in the old town to save money, but many evenings I climb the stone steps in the hillside, up to the ramparts, for the view. Buildings in the old town are decrepit, the streets are loud; but on the mountainside, the old stone gleams, passionflowers drip, the ocean can be seen frothing lavishly against the seawall.

I read further into Kant. I become suspicious of the fine biases of apperception, of the way my mind massages experience and makes it cohere into a world. My ethical crises are regular. Dark irony, as with the repurposing of the Spanish castle, seems to filigree each noun. It can cripple me when I am sober, trap me in my head, my room. I am told that the vast majority of tourist goods are sold by the military, prinked up in its LLCs (Gaviota; Caracol) like bad drag, and that the hotels and restaurants are run by it. It is impossible for me to live even a bare existence without perpetuating state power.

Aníbal changed his name to Richard at 18, and worked for an insurance company until Parkinson’s curled him up and made him paranoid, cruel. Fernando made money and lost it three times, had three bypasses, and wound up selling video-surveillance systems.  Enrique was a portrait painter until Parkinson’s made his hands shake too much. They don’t like to dwell on their health, but they remember, in Havana, running after the DDT truck that rumbled by every afternoon, and playing in that mist, and they wonder.

Enrique was a portrait painter until Parkinson’s made his hands shake too much. They don’t like to dwell on their health, but they remember, in Havana, running after the DDT truck that rumbled by every afternoon, and playing in that mist, and they wonder.

I linger in this town because it is small and lush, and I feel forgotten, free. It is the end of the year, and I’m writing a cycle of poems around the winter solstice, my memories of my mother, and ideas plucked from analytical philosophy. I get to know certain people: a man my age who pedals a bicitaxi, the daughter of my landlady, the man I got drunk with one night.

December 20th

Storms all day, sweeping in, lasting minutes.

Wearing a raincoat,

A transparency walks along the ocean.

This is his way of atoning for the evening:

Observing the city without proposing himself.

His way of making pilgrimage:

He passes from the mind of the man

Arranging tomatoes and rice on a blanket

To the mind of three schoolgirls returned from an errand,

Then he moves to the corner.

A lightness tumbles down all around,

Very difficult to tamp, not the rain, and a sense of age,

And a power of collation.

From the ocean

Is suspended the image of a hill

From which the equinox can be described.

From the center, in the afternoon,

mournful bells clanged and white.

On December 24 I am celebrating in a café with a gaggle of German retirees; Naima, a blonde Swiss German; and Serguey, a local, who is trying to seduce Naima. I translate, which for a while is faintly fun. Naima is initially friendly toward Serguey, then after an hour becomes bored and ignores him. Serguey senses this and begins to drink hard and fast. We, the tourists, have been buying the bottles. The mood becomes weird, and it is decided that we will go down the street to the Christmas Cabaret at midnight.

When we stand up, Serguey stands up and begins to yell. Naima has gone on ahead a few minutes ago. I catch some of what he says. He says we owe him two dollars for ice. His eyes are bloodshot. When he breaks a rum bottle on the table and holds it to the Karl’s neck (Karl is in his seventies, a small man), I grab his wrists and grip hard, digging my fingers in, wrestling him back, until he lets go of the shard.

After a minute he seems calm. I pick up my jacket to go and he throws a glass of cola in my face. I punch him in the head and then I’m kneeling with my knee on his neck in the street. In another minute the police appear. I see them talking to the waitress, to someone watching from her stoop. They don’t talk to me. Then they have Serguey in handcuffs and then an unmarked van comes and they put him in the back.

For the next week, when I walk around the city men I don’t know raise their fists and mime jabs at me. Papa!, they cry, feinting left. (I’ve let my beard grow.) I don’t see Serguey around. When, tentatively, I ask Alejo—who sells little grilled shrimp skewers by the seawall, and plays middleman to tourists looking for cheap rooms—what happened to him, he shrugs. Se le desapareció, he says.

December 20th

As two animals once regarded each other on the porch

Of your childhood, skew-toothed and unlikely,

So too the immobile ceiling fan and you.

And the fault crouches on the other side of that blade.

It is the evening of the day of collapsed distance

And voluntary time. Thus at the dinner of discolored fruits

Tropical birds keep alighting by the bowl,

Looking vulnerable, and shrieking.

Shrieking as if the knife were the real,

This grapefruit, its synthesis,

And this bore on you.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Noah Warren is the author of The Destroyer in the Glass, winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets. He is the recipient of fellowships from Yale and Stanford, and lives in Paris.

Crescent Park, New Orleans

The best place to watch ships. They move tentatively in the Mississippi's currents and curves, always flanked by tugboats. Vast webs of commerce become briefly visible here.