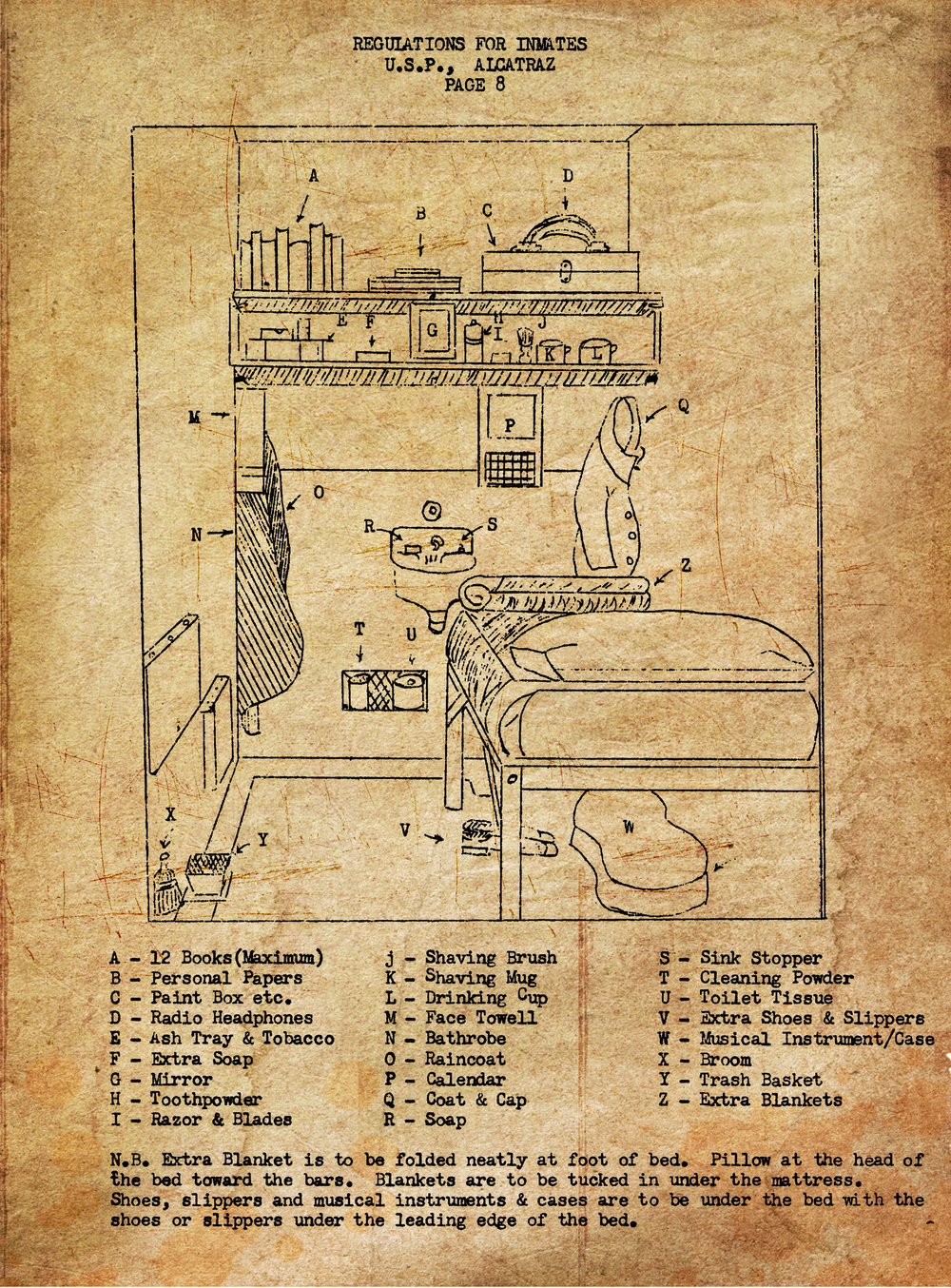

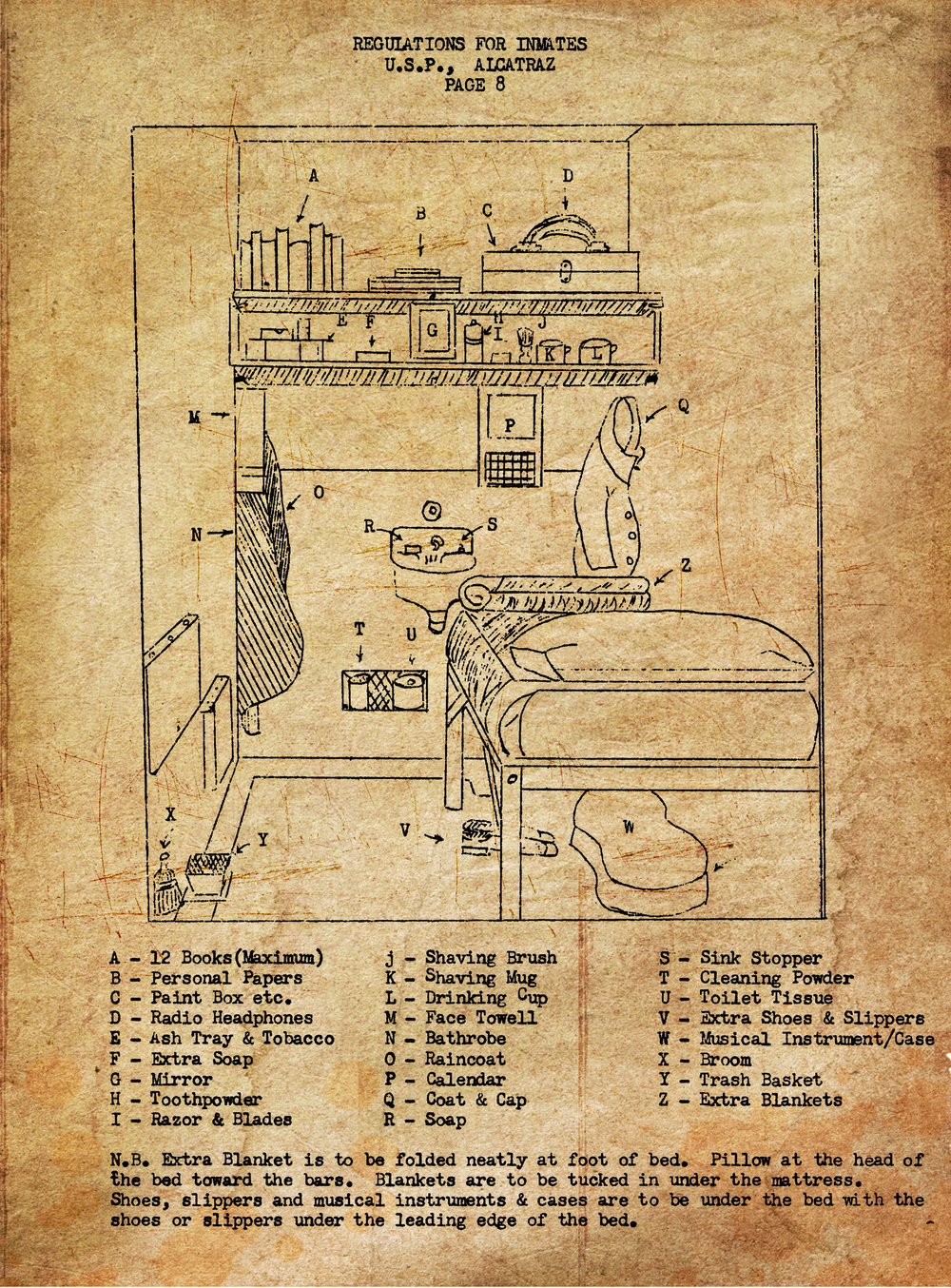

About a year ago I saw a diagram of a prison cell at Alcatraz, titled “Regulations for Inmates”—not an aerial map but a kind of schematic, an illustrated view into a cell with its fourth wall of locked bars removed, its contents labeled. It looks like a page from a children’s workbook, an exercise in matching names to objects. The objects are grouped into pairs as needed, such as “Ash Tray & Tobacco,” so as to end up with exactly 26 items, from A to Z: an alphabet’s worth of worldly goods. The paper itself is sepiaed and cross-hatched in a way that looks almost fake, like painted-on weathering. It reminds me of a treasure map I made when I was 7 or 8—I burned the edges with a match so it would look authentically antique. I saved the image of the cell to my laptop and filed it away.

About a year ago I saw a diagram of a prison cell at Alcatraz, titled “Regulations for Inmates”—not an aerial map but a kind of schematic, an illustrated view into a cell with its fourth wall of locked bars removed, its contents labeled. It looks like a page from a children’s workbook, an exercise in matching names to objects. The objects are grouped into pairs as needed, such as “Ash Tray & Tobacco,” so as to end up with exactly 26 items, from A to Z: an alphabet’s worth of worldly goods. The paper itself is sepiaed and cross-hatched in a way that looks almost fake, like painted-on weathering. It reminds me of a treasure map I made when I was 7 or 8—I burned the edges with a match so it would look authentically antique. I saved the image of the cell to my laptop and filed it away.

What was it about this image that struck me?

Sometimes attraction is recognition—familiarity—in disguise. Looking at the diagram a year later, I suddenly realize what it reminds me of: Bedroom in Arles by Vincent van Gogh.

The view into the room, small and square, is the same, as is the placement of the bed. There are many other parallels, a bit uncanny: Item Q (“Coat & Cap”) appears in the same place as the coat and hat rack in the Arles bedroom, on the back wall behind the bed. Both rooms have a towel hanging on the left-hand wall. Where the prison cell has a sink against the back wall, the bedroom in Arles has a pitcher of water set in a basin on a table. Each back wall has a mirror, though only the bedroom in Arles has a window. In both cases, the mirror is theoretical, an empty frame that reflects nothing. (Does this distract from, or call attention to, the missing wall?)

The view into the room, small and square, is the same, as is the placement of the bed. There are many other parallels, a bit uncanny: Item Q (“Coat & Cap”) appears in the same place as the coat and hat rack in the Arles bedroom, on the back wall behind the bed. Both rooms have a towel hanging on the left-hand wall. Where the prison cell has a sink against the back wall, the bedroom in Arles has a pitcher of water set in a basin on a table. Each back wall has a mirror, though only the bedroom in Arles has a window. In both cases, the mirror is theoretical, an empty frame that reflects nothing. (Does this distract from, or call attention to, the missing wall?)

Another notable difference: The prison cell does not have art on its walls, unless you count the calendar. (I had never noticed, but one of the paintings in Bedroom in Arles appears to be a Van Gogh self-portrait.) However, an inmate at Alcatraz is expected, it seems, to have art in his life: Item C on the top shelf is identified as a “Paint Box etc.” There are headphones sitting on it, so the inmate may listen to the radio. His “musical instruments & cases” (in this case, a guitar) should be stored under the bed—he is expected to have them. (It’s so easy to imagine, isn’t it, a guitar under the bed in Arles?) It is understood that he will read; every prisoner was given a library card upon entrance (though the library was censored). He may store books in his cell—“12 Books (Maximum)”—and perhaps respond to what he reads, storing those notes among his “Personal Papers” (Item B). It suggests an almost romantic interlude, like a writing retreat, of time alone with one’s thoughts.

I once saw a silly, forgettable movie with a single memorable scene: Melanie Griffith pauses in front of a late van Gogh painting at what is probably the National Gallery. (Could it have been Farmhouse in Provence? Or First Steps, after Millet?) She performs being-struck-by-an-image. She says, “God, it’s so small, but it’s like it’s bigger than the whole room.”

Reflecting on the line now, I take it to mean that the van Gogh is steeped in humanity—that it seems large because it’s so full of life. Isn’t that why people love Bedroom in Arles, even though there are no living humans in it? (I say this as though a “life-size” person in the room would be more real somehow than the people in the meta-paintings on the bedroom’s wall.) The room feels full of a person, because the bedding is slightly rumpled, the chairs are slightly askew. Everything looks recently used; we imagine it would smell like a person.

Somehow I find the Alcatraz bedroom equally poignant—but it’s not the artfulness of the diagram that touches me, it’s the language of the regulations, which have a kind of tenderness of detail: “Shaving Mug,” but “Drinking Cup.” “Toilet Tissue.” “Extra Shoes & Slippers.” And there’s the nota bene at the end: “Extra Blanket is to be folded neatly at foot of bed.” It’s delivered with the gentle tone you might use to address a sleepy child. The coat on its hook even looks somewhat childlike: the row of buttons curving as though over a round belly.

It’s all so at odds with the context. Alcatraz was a high security prison. Between 1934 and 1963, there were 14 attempted escapes involving 36 men. It seems unlikely that inmates were treated with patience and encouraged to nurture their musical talent.

According to a site called Alcatraz History, which has the feel of a fan site, if you can be a fan of a prison: “At Alcatraz, a prisoner had four rights: food, clothing, shelter, and medical care. Everything else was a privilege that had to be earned.” But the same site notes that one former prisoner, Willie Radkay, “considered his time at Alcatraz to be better than at any other penitentiary.” He cherished the privacy of his cell and the relatively good food.

The site also includes a photograph of a “typical cell at Alcatraz” from 1956, which has art hanging on its back walls (horses) and a painting of Jesus displayed on an easel: “This is the cell of one of several prisoners permitted to pursue oil painting.” Competing realities.

Is the diagram of the regulation cell a kind of propaganda, portraying the agitated prisoner’s experience as one of calm and artful solitude, a life well-lived? Or was it intended to be beneficent, an argument against inhumanity to the incarcerated? I can’t say.

I wonder, too, if the artist had Arles in mind.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Elisa Gabbert, a poet and essayist, is the author of three collections: L’Heure Bleue, or the Judy Poems; The Self Unstable; and The French Exit.

She currently lives at the unlucky corner of 13th and Columbine.