Legend

Treasure

According to the biographer and historian Fawn M. Brodie, the list of the instruments used to hunt for treasure in early 19th century America include: witch-hazel sticks and mineral rods; books of spells and incantations; crystals, stuffed toads, and seer stones; a black sheep that was taken to the treasure’s location then led around with its throat cut and bleeding.

Though these instruments might sound antiquated or anachronistic, they testify to a treasure seeker’s desire to hit the mark. There is no narrative turn of events that quite matches treasure’s discovery. Early 19th century America produced a wildfire of religious revivalism as well as a hunger for exploration, often conflating the two. Treasure seeking became both an act of faith and an act of desperation, but always a concept whose worth was so automatically assumed that now we rarely wonder whether we actually want to find it.

Though these instruments might sound antiquated or anachronistic, they testify to a treasure seeker’s desire to hit the mark. There is no narrative turn of events that quite matches treasure’s discovery. Early 19th century America produced a wildfire of religious revivalism as well as a hunger for exploration, often conflating the two. Treasure seeking became both an act of faith and an act of desperation, but always a concept whose worth was so automatically assumed that now we rarely wonder whether we actually want to find it.

For our fifth issue, we asked thirteen writers and artists to search for treasure in maps of sea floors and Gulf Streams, the Aztec Empire and the World’s Fair.

In Michael Sheehan’s story of modern-day conquistadors, “The Making of Our Unfinished Western,” and Christopher Knapp’s seafaring adventure, “Salvage,” characters make unexpected discoveries that don’t seem to hold the treasure first promised. These characters—Sheehan’s pair of opportunistic filmmaker brothers and Knapp’s sailing crew who find themselves in over their heads—fail to recognize that the search for treasure can corrupt, bringing with it violence, conquest, and ill consequence. They would be wise to heed Joni Tevis’s words in “Should You Venture Here Alone,” her essay that alights upon the rumor of a wrecked ship near the Salton Sea: “For a Thing-finder to win, someone else has to lose.”

Treasure can be at the top of a mountain or hidden in plain sight. It can wait for us in some heavenly realm or, as in Beth Steidle’s “The Newfoundland Exams” and Lucy Schiller’s “Sweep,” lurk under the surface. Steidle’s essay on the forms of Newfoundland finds “divers reach[ing] out to pet the blue underbelly” of icebergs. Schiller studies a contemporary kind of divining rod—the metal detector—and joins a group of its enthusiasts in Antlers, Oklahoma. Both the detectorists and Schiller search for the present and the past, what’s of value and what’s trash. “Simile, maddening, keeps detectorists hunting,” Schiller writes. “For in it, somewhere, out of view, an authenticity itches and shines.”

In other words, can one thing really stand in for another? Adam Tipps Weinstein’s “The Strange Ratio of Treasure Island” posits a map that corresponds exactly with its territory. Ruth Madievsky’s “Birthright” and Tamas Dobozy’s “Neglected Lands” trace the contours of statelessness, the treasure lost when one cannot return home. Displaced, they conduct the search for home’s treasure the only way one can: by imagining a cartography. Matthew Vollmer’s “101 Oak Street” takes this one step further by leaving the treasure and removing the map.

And what would an issue on treasure be without a treasure hunt itself? We asked Albert Goldbarth, the famously analog poet and essayist, to hide a poem within our digital issue. The result is, in his words, “a sonnet-y type thing” concealed throughout the issue, waiting for our readers to search and assemble. In this case, Territory has become the map. We hope you enjoy the hunt.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Tamas Dobozy’s “Neglected Lands” imagines a series of “hand-drawn maps in a hundred different styles--topographical; collages cut from photographs; watercolors from the perspective of a sidewalk; prose descriptions.” Together they evoke, in the author’s words, “the benefits of statelessness.”

Tamas Dobozy’s “Neglected Lands” imagines a series of “hand-drawn maps in a hundred different styles--topographical; collages cut from photographs; watercolors from the perspective of a sidewalk; prose descriptions.” Together they evoke, in the author’s words, “the benefits of statelessness.”

The story is paired with a map made using similar methods. The map’s artist, Tim Stuemke, had this to say about his work: “The collage is an abstract response to the thought of barriers to a destination, and the choices we make along the way in that journey. The blocks created by the maps are a confining element. While the open field and text denote a possible way forward. But of course no place is ever what it seems.”

×

Albert Goldbarth’s “15th / 21st” is not a map or a response to a map, in the traditional sense, but it certainly is a treasure. Albert is a writer who is difficult to track down, and so too is his poem. Hidden throughout the farthest corners of this, Territory’s fifth issue, are the fourteen lines of Albert’s sonnet where they await discovery. These lines are hard to find, but don’t worry; Albert’s trusty assistant, Otto, is here to help.

Geetha Iyer’s “Least Concern” maps where the home ranges of frogs and people overlap. While the essay considers the mental maps of the green and black poison frog, Dendrobates auratus, it is paired with a map (Pasukonis, A. et al, 2014) depicting the navigation abilities of a related species, the brilliant-thighed poison frog, Allobates femoralis.

Geetha Iyer’s “Least Concern” maps where the home ranges of frogs and people overlap. While the essay considers the mental maps of the green and black poison frog, Dendrobates auratus, it is paired with a map (Pasukonis, A. et al, 2014) depicting the navigation abilities of a related species, the brilliant-thighed poison frog, Allobates femoralis.

The author had the following to say about the essay’s origins: “‘Least Concern’ began at the back of my house on Ancon Hill in Panama, stumbled into scientific publications online, traveled via flash drive to the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology in Oregon, and returned semi-formed to Panama just in time for the 2017 wet season, when the poison frogs come out. It is possible to follow the path of a green and black poison frog with a very long length of marked twine and GIS mapper, but it is also possible to sit in one place and just watch the frog think about where it wants to go next. Or sit in Oregon and wonder where the frogs you left behind will go next. Or read scientists’ accounts from the 1940’s through to present day of frogs of yore figuring out their next steps. Both the frog and the human observer have a sense of imagination, and it’s surely possible that sometimes their sense of destination overlaps.”

A complete list of references, including species range maps, territory maps, and mental maps:

Barrio-Amorós. 2010, March 16. A suggestion about common nomenclature for dendrobatids. From: dendrobates.org. Accessed 5 July 2016.

Dunn, E.R. 1941. Notes on Dendrobates auratus. Copeia 1941.2: 88–93.

Eaton, T.H., Jr. Notes on the life history of Dendrobates auratus. Copeia 1941:2: 93–95.

Feller, A.E. and Hedges, S.B. 1998. Molecular evidence for the early history of living amphibians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 9.3: 509–516. DOI: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0500

Grant, T. et al. 2006. Phylogenetic Systematics of Dart-Poison Frogs and their Relatives (Amphibia: Athensphatanura: Dendrobatidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History: 1–262. DOI: 10.1206/0003-0090(2006)299[1:PSODFA]2.0.CO;2

Gray, H.M., Summers, K. and Ibáñez D., R. 2009. Kin discrimination in cannibalistic tadpoles of the Green Poison Frog, Dendrobates auratus (Anura, Dendrobatidae). Phyllomedusa 8.1: 41–50. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v8i1p41-50

Liu, Y., Day, L.B., Summers, K., and Burmeister, S.S. 2016. Learning to learn: advanced behavioural flexibility in a poison frog. Animal Behavior 111: 167–172. DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.10.018

Longcore, J.E., Pessier, A.P., and Nichols, D.K. 1999. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis gen. et sp. nov., a chytrid pathogenic to amphibians. Mycologia 91.2: 219–227.

Oliver, J.E. and Shaw, C.E. 1953. The amphibians and reptiles of the Hawaiian islands. Zoologica 38.2: 65–95.

Ostrowski, T. n.d. Dendrobates auratus (Girard, 1855). From: dendrobates.org. Accessed 5 July 2016.

Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. amphibianrescue.org. Accessed 1 June 2016.

Pašukonis, A. et al. 2014. Poison frogs rely on experience to find the way home in the rainforest. Biology Letters 10. 11: 20140642. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0642

Pašukonis, A. et al. 2016. The significance of spatial memory for water finding in a tadpole-transporting frog. Animal Behaviour 116: 89–98. DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.02.023

Patrick, L.D. and Sasa, M. 2009. Phenotypic and molecular variation in the green and black poison-dart frog Dendrobates auratusi (Anura: Dendrobatidae) from Costa Rica.

Santos, J.C., Tarvin, R.D., and O’Connell, L.A. 2016. A review of chemical defense in poison frogs (Dendrobatidae): Ecology, pharmatokinetics, and autoresistance. Chemical Signals in Vertebrates 13: 305–337. Springer International Publishing. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-22026-0_21

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. n.d. Dendrobates auratus Girard 1855.From: Amphibians of Panama. Accessed: 5 July 2016.

Solís, F. et al. 2008. Dendrobates auratus. From: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T55174A11250892.en. Accessed 20 June 2016.

Stynoski, J., Schulte, L.M., and Rojas, B. 2015. Quick guide: Poison frogs. Current Biology 25:21: R1026–R1028. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.044

Summers, K. 1989. Sexual selection and intra-female competition in the green poison-dart frog, Dendrobates auratus. Animal Behavior 37.5: 797–805. DOI: 10.1016/0003-3472(89)90064-X

Summers, K. 1990. Paternal care and the cost of polygyny in the green dart-poison frog, D. auratus. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 27: 307–313. DOI: 10.1007/BF00164001

Summers, K. 2014. Sexual conflict and deception in poison frogs. Current Zoology 60.1: 37–42. DOI: 10.1093/czoolo/60.1.37

Summers, K. and Clough, M.E. 2001. The evolution of coloration and toxicity in the poison frog family (Dendrobatidae). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98.11: 6227–6232. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.101134898

Summers, K. and McKeon, C.S. 2004. The evolutionary ecology of phytotelmata use in neotropical poison frogs. Miscellaneous publications / University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, 193: 55–73.

Toft, C.A. 1981. Feeding ecology of Panamanian litter anurans: Patterns in diet and foraging mode. Journal of Herpetology 15.2: 139–144.

Waldman, B. 1991. Kin recognition in amphibians. Kin recognition, 162–219.

Wells, K.D. 1978. Courtship and parental behavior in a Panamanian poison-arrow frog (Dendrobates auratus). Herpetologica 34.2: 148–155.

Wells, K.D. 2007. The Ecology and Behavior of Amphibians. University of Chicago Press.

×

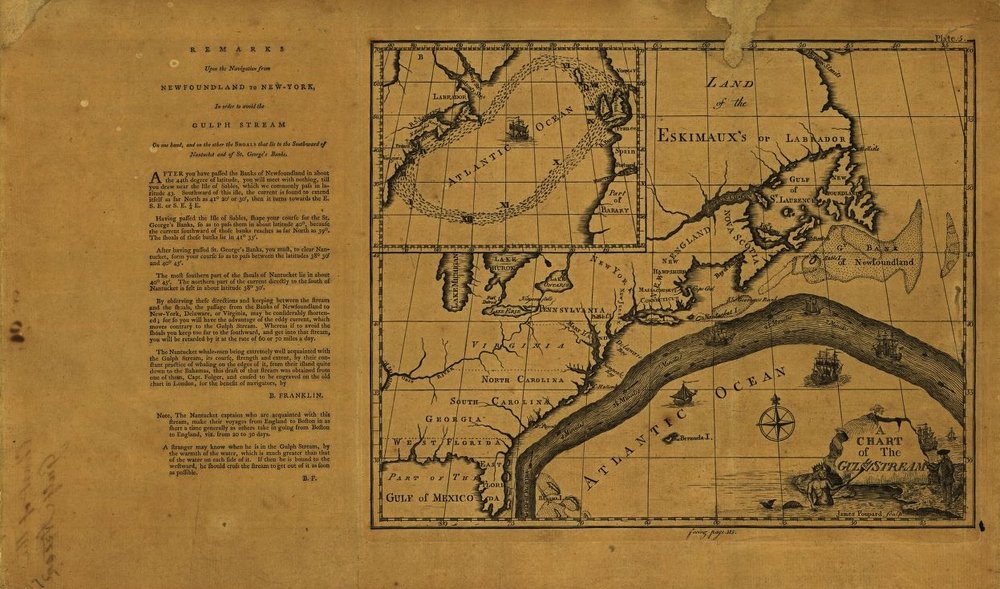

Chris Knapp’s “Salvage” takes place within the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream was first mapped by Ben Franklin who, among his other accomplishments, published “A Chart of the Gulf Stream” in a 1786 issue of Transactions of American Philosophy with the subheading, “Remarks Upon the Navigation from Newfoundland to New York.” A note at the bottom of the chart supplies a warning to those who find themselves in the same situation as Knapp’s characters: “A stranger may know when he is in the Gulf Stream, by the warmth of the water, which is much greater than that of the water on either side of it. If then he is bound to the westward, he should cross the stream to get out of it as soon as possible.”

Chris Knapp’s “Salvage” takes place within the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream was first mapped by Ben Franklin who, among his other accomplishments, published “A Chart of the Gulf Stream” in a 1786 issue of Transactions of American Philosophy with the subheading, “Remarks Upon the Navigation from Newfoundland to New York.” A note at the bottom of the chart supplies a warning to those who find themselves in the same situation as Knapp’s characters: “A stranger may know when he is in the Gulf Stream, by the warmth of the water, which is much greater than that of the water on either side of it. If then he is bound to the westward, he should cross the stream to get out of it as soon as possible.”

×

Ruth Madievsky’s “Birthright” is a response to the many maps of Moldova in the private collection of Bernhard Paul Moll (1697-1780), an ambassador to the Archduchy of Austria who used the wealth that position afforded to collect maps. The oldest map in this collection, Johann Hoffmann’s (1668), captures an era when Moldova was split into smaller regions including Podolia and Bessarabia, hence the camel-drawn carriages.

Ruth Madievsky’s “Birthright” is a response to the many maps of Moldova in the private collection of Bernhard Paul Moll (1697-1780), an ambassador to the Archduchy of Austria who used the wealth that position afforded to collect maps. The oldest map in this collection, Johann Hoffmann’s (1668), captures an era when Moldova was split into smaller regions including Podolia and Bessarabia, hence the camel-drawn carriages.

Johann van der Bruggen’s 1737 map of a complete “Moldavia” (pictured) embellishes its geography with an illustration of a person sitting among horses, holding a scroll that reads “Admiratur equos,” a reference to Book XIV of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, about “Picus, the son of Saturn...a king in the regions of Ausonia, an admirer of horses useful in warfare.” Picus was an especially attractive man, but much to the dismay of Circe, a goddess of magic, he was faithful to his wife, Canens. When Circe attempted to seduce him, Picus “roughly repel[led] her and her entreaties” and so Circe transformed Picus into a woodpecker.

×

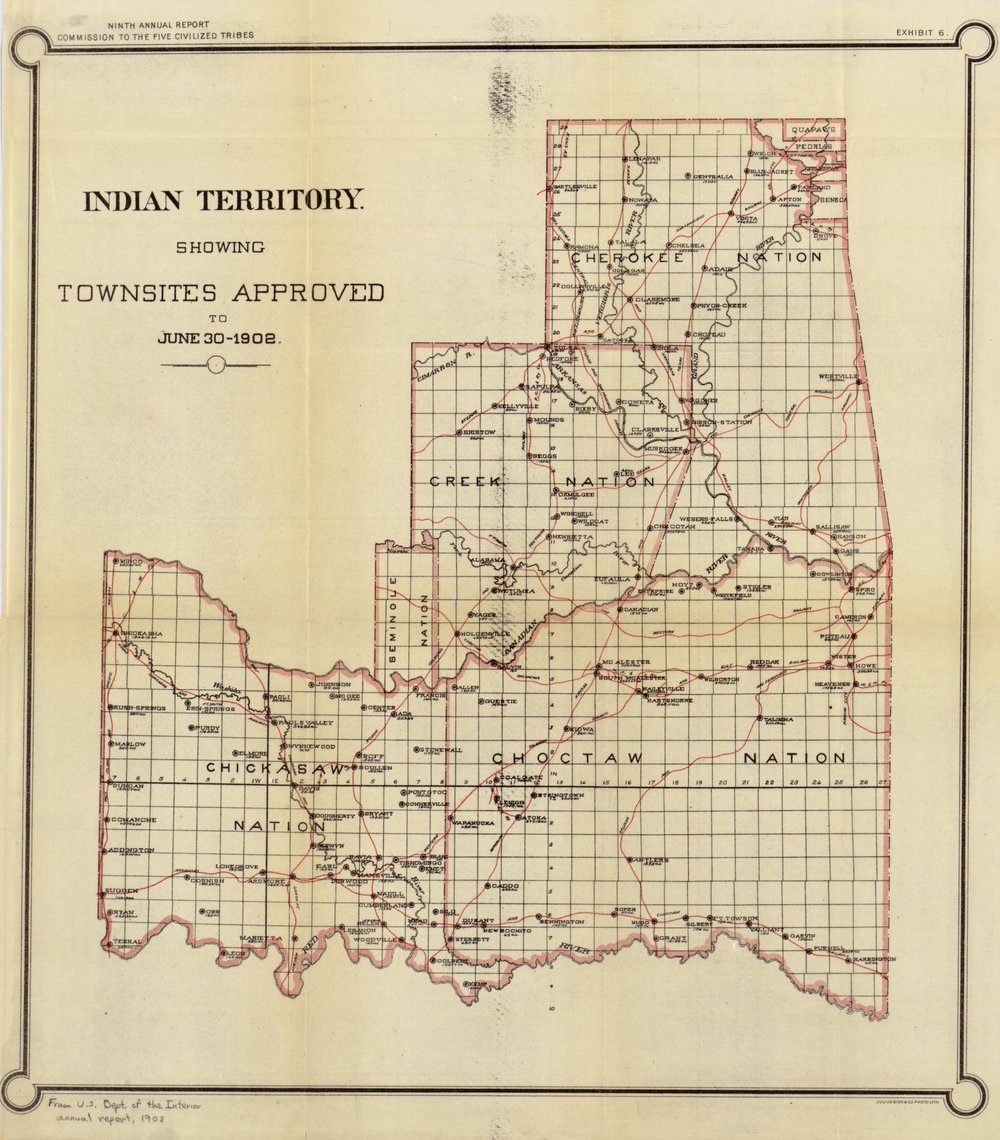

Lucy Schiller’s “Sweep” maps the treasure hunting of a group of metal detectorists in southeastern Oklahoma. This part of Oklahoma, home to the Choctaw Nation, is depicted in a 1902 map commissioned by the U.S. Department of the Interior entitled “Indian Territory showing townsites approved.” Contemporary maps in Oklahoma are entitled “Maps showing progress of allotment in Creek Nation” and “Indian Territory showing railroad systems.” The proprietary language within these titles is a result of the Oklahoma land rush of 1889, in which nearly two million acres of Tribal land were opened up to white settlement. On April 22nd, a cannon boomed from Fort Reno to mark the legal time of entry and thousands of settlers poured in. The term Sooner applies to those settlers who seized land and property before it was legally permissible, a strategy which might find some echoes in Schiller’s subject matter.

Lucy Schiller’s “Sweep” maps the treasure hunting of a group of metal detectorists in southeastern Oklahoma. This part of Oklahoma, home to the Choctaw Nation, is depicted in a 1902 map commissioned by the U.S. Department of the Interior entitled “Indian Territory showing townsites approved.” Contemporary maps in Oklahoma are entitled “Maps showing progress of allotment in Creek Nation” and “Indian Territory showing railroad systems.” The proprietary language within these titles is a result of the Oklahoma land rush of 1889, in which nearly two million acres of Tribal land were opened up to white settlement. On April 22nd, a cannon boomed from Fort Reno to mark the legal time of entry and thousands of settlers poured in. The term Sooner applies to those settlers who seized land and property before it was legally permissible, a strategy which might find some echoes in Schiller’s subject matter.

×

Michael Sheehan’s “The Making of Our Unfinished Movie” tells two parallel stories: the unexpected discoveries made by two brothers filming a movie in the Sonoran Desert and the conquistador Hernán Cortés’s arrival in Tenochtitlan. The “Map of Tenochtitlan,” a woodcut published in Nuremberg, most likely stems from a drawing done by one of Cortés’s men, who in turn may have based his drawing off an indigenous map of the city. The map is oriented south-north and displays the causeways and islands that linked the city within Lake Texcoco. On the far left, in a separate illustration of the Caribbean islands, one may spot Cuba’s tip. This map, made in 1524, was the only known image of Tenochtitlan in Europe at the time. Cortés arrived in the city in 1519 and, by 1521, he had destroyed it.

Michael Sheehan’s “The Making of Our Unfinished Movie” tells two parallel stories: the unexpected discoveries made by two brothers filming a movie in the Sonoran Desert and the conquistador Hernán Cortés’s arrival in Tenochtitlan. The “Map of Tenochtitlan,” a woodcut published in Nuremberg, most likely stems from a drawing done by one of Cortés’s men, who in turn may have based his drawing off an indigenous map of the city. The map is oriented south-north and displays the causeways and islands that linked the city within Lake Texcoco. On the far left, in a separate illustration of the Caribbean islands, one may spot Cuba’s tip. This map, made in 1524, was the only known image of Tenochtitlan in Europe at the time. Cortés arrived in the city in 1519 and, by 1521, he had destroyed it.

×

Beth Steidle’s “The Newfoundland Exam” combines text and image to create a visual essay in the form of a multiple-choice test. The images are of the sea floor surrounding Newfoundland and the map accompanying the piece was published in 1760 and repetitively titled, “A New Map of the Most Frequented Part of New Found Land.” A subheader declares: “The Inland Parts of This Island Are Unknown.” Since the map foregoes the less frequented parts, it does not depict L'Anse aux Meadows, a Viking settlement on the northern tip of the island dating from 1006 and the only site of authenticated Norse settlement in North America. To the north of Newfoundland, of course, is the province of Labrador.

Beth Steidle’s “The Newfoundland Exam” combines text and image to create a visual essay in the form of a multiple-choice test. The images are of the sea floor surrounding Newfoundland and the map accompanying the piece was published in 1760 and repetitively titled, “A New Map of the Most Frequented Part of New Found Land.” A subheader declares: “The Inland Parts of This Island Are Unknown.” Since the map foregoes the less frequented parts, it does not depict L'Anse aux Meadows, a Viking settlement on the northern tip of the island dating from 1006 and the only site of authenticated Norse settlement in North America. To the north of Newfoundland, of course, is the province of Labrador.

×

Joni Tevis’s “Should You Venture Here Alone” responds to a treasure map made by the Gleem Toothpaste company as part of a promotional contest advertised in a 1958 issue of Life. Close readers of the map may notice that contest entries are to be mailed to an address in Cincinnati, Ohio, which would indicate that Gleem’s parent company was Procter & Gamble, headquartered there. If you’ve never heard of Gleem, that’s because Procter & Gamble folded it into another toothpaste brand they owned, Crest, renaming Gleem “Crest Fresh and White.” An online article entitled “Whatever Happened to Gleem?” theorizes that Gleem declined in popularity because it continued to refer to its product as toothpaste, while its competitors opted for shorter, catchier terms such as “gel” or “paste.” Whether Joni Tevis’s presence at the Colgate Writers’ Conference had anything to do with the engendering of her essay is a question better left for the author.

Joni Tevis’s “Should You Venture Here Alone” responds to a treasure map made by the Gleem Toothpaste company as part of a promotional contest advertised in a 1958 issue of Life. Close readers of the map may notice that contest entries are to be mailed to an address in Cincinnati, Ohio, which would indicate that Gleem’s parent company was Procter & Gamble, headquartered there. If you’ve never heard of Gleem, that’s because Procter & Gamble folded it into another toothpaste brand they owned, Crest, renaming Gleem “Crest Fresh and White.” An online article entitled “Whatever Happened to Gleem?” theorizes that Gleem declined in popularity because it continued to refer to its product as toothpaste, while its competitors opted for shorter, catchier terms such as “gel” or “paste.” Whether Joni Tevis’s presence at the Colgate Writers’ Conference had anything to do with the engendering of her essay is a question better left for the author.

×

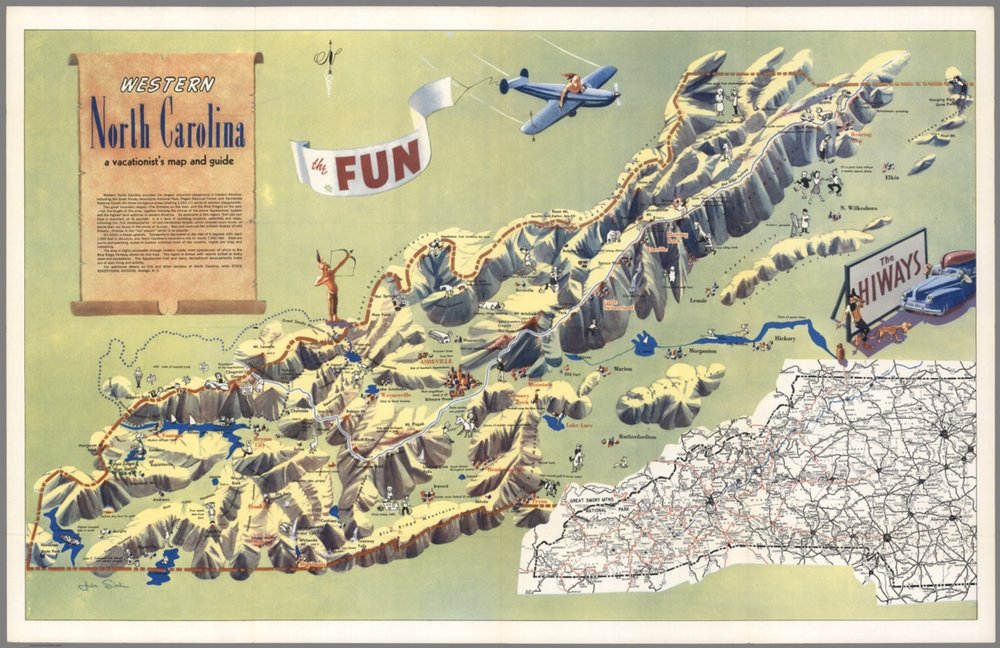

Matthew Vollmer’s “101 Oak Street” maps the site of a beloved childhood house in Andrews, North Carolina, as the essay’s full title, “from the Lost Treasures of Cherokee County: 101 Oak Street,” suggests. Detailed maps of Andrews, NC proved difficult to find (as one editor discovered after a call to the Andrews’ town hall), which might justify the aptitude of the essay’s title.

Matthew Vollmer’s “101 Oak Street” maps the site of a beloved childhood house in Andrews, North Carolina, as the essay’s full title, “from the Lost Treasures of Cherokee County: 101 Oak Street,” suggests. Detailed maps of Andrews, NC proved difficult to find (as one editor discovered after a call to the Andrews’ town hall), which might justify the aptitude of the essay’s title.

In its place, “Western North Carolina: A Vacationist’s Map and Guide” serves as a counterpoint to Vollmer’s essay. If the essay brings a local’s sense of time to the town and its treasures, “A Vacationist’s Map,” as can be surmised from its title and cartoon airplane banner screaming “FUN,” is intended for tourists. Near Andrews’ marker on the map are two details: one, referring to Lake Hiwassee, advertises the “highest overspill dam in the world” and the second, at the foot of the Snowbird Mountains, says simply: “DeSoto dug here for gold.” There’s no word on whether he found it.

×

Adam Tipps Weinstein’s “The Strange Ratio of Treasure Island” maps “the perfect correspondence of landscape and information” seen in Ruth Taylor’s 1939 map, “A Cartograph of Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay.” The map was commissioned for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939 and 1940, which celebrated the openings of both the Golden Gate and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Treasure Island, a manmade, artificial island, was commissioned and built for the Exposition as well. One may find, in its legend, both the utopian and the banal: the Court of Honor and Tower of the Sun is a stone’s throw away from the Food and Beverages Bldng. Though the map’s sea monster is dubious, whales are known to stray from their Mexico-to-Alaska migrations to feed in the San Francisco Bay, the most famous of which, Humphrey the Whale (a humpback), deviated twice, first in 1985 then in 1990.

Adam Tipps Weinstein’s “The Strange Ratio of Treasure Island” maps “the perfect correspondence of landscape and information” seen in Ruth Taylor’s 1939 map, “A Cartograph of Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay.” The map was commissioned for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939 and 1940, which celebrated the openings of both the Golden Gate and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Treasure Island, a manmade, artificial island, was commissioned and built for the Exposition as well. One may find, in its legend, both the utopian and the banal: the Court of Honor and Tower of the Sun is a stone’s throw away from the Food and Beverages Bldng. Though the map’s sea monster is dubious, whales are known to stray from their Mexico-to-Alaska migrations to feed in the San Francisco Bay, the most famous of which, Humphrey the Whale (a humpback), deviated twice, first in 1985 then in 1990.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.