According to a metal detecting forum, they hunt at Amusement Parks, Carnival Sites, Old Drive-In Theaters, Old Home Sites, Children’s Summer Camps, Fishing Camps, Hunting Camps, Under Grandstands and Bleachers, Under Ski Lifts, Old Campgrounds, Roadside Produce Stands, and Around Any Resort Area.

“The past” is composed of two parts, time and place. So are the maps detectorists use to determine where they’ll hunt, where treasure sits. On one map, leafy green, there’s a homestead; on another, it’s gone to make way for a railroad. This is where they’ll go with their Garrett AT Pro on the weekend.

Ray Sanchez’s Fed Ex route takes him into the country, the real country, he says, of rural Arkansas. He’s a thin man. He tells me that, as he drives, he scans the sides of the asphalt for jonquils because they tell him where old houses used to be. Someone’s hands planting the bulbs a century and a half ago. Cutting them in the spring. He keeps a map close by the wheel so that he can circle approximately where he sees the yellow flashes. Some years it’s all yellow outside, the map highlighted like a field, some years the flowers don’t surface and he wonders why, and if this is the year they stop for good, and how he’ll find the past in the future.

×

The first metal detector was invented by Trouvé, a man whose name translates to “found.”

×

There is an easy point to be made about metal detecting bringing the detectorist in touch with the past. Metal detectorists make this point all the time. Personally, I call nowhere home; that is, my family moved repeatedly during my childhood and adolescence, and so I’ve thought that perhaps the reason I feel pulled towards metal detecting is not for the purported wealth and mystery shining below my feet, but the allure of the past made specific, holdable for once. Before meeting the detectorists, I did all the research I could: lurked on their message boards, watched YouTube videos of men swinging in wet sand and over chert hills, memorized the nine-point code of ethics (“Will use thoughtfulness, consideration, and courtesy at all times.” “WILL NOT destroy property, buildings, or what is left of ghost towns and deserted structures.”) They spoke, again and again, of a “window into the past” via the object they might uncover. But a window is a sheet, or two sheets, of glass. As much as we cannot rely on words to convey the totality of experience, though we necessarily continue to ask them to do so, we cannot rely on transparency to show us a time and a place we never knew. More accurate would be those bad frescoes at certain Italian restaurants, say, in the strip malls near my first home in San Diego. Those kinds of frescoes emulate windows, although they are usually painted somewhere on the beige walls where such expansive windows would never go. They show us not a real place or time but an imagined one: between the two glinting painted-bay windows we see, in the distance on the wall, an unmistakably Tuscan countryside’s tall cypress trees, or maybe another restaurant, imaginary, across an imaginary cobblestoned street, with imaginary yellow-and-white striped chairs sitting out front that this restaurant, the one in which we are currently sitting and eating, does not claim to own. A map of what we wish was there, otherwise known as a painting.

×

In Oklahoma, near a town called Antlers, at a treasure-seeking convention's annual rendezvous, I prepared to metal detect for the first time alongside Ray and fifty other men and one woman, believers in the power of the artifact to transport, the rightfulness of ownership, the obviousness of treasure’s allure. This was a “planted” hunt, meaning Keith, the Vice President, had spent the day seeding the ground with coins he’d purchased online. Now it was nine p.m.; someone’s glowing RV by the river and the moon provided the only light. The point was not to discover “actual” treasure, but to amass as much as quickly as possible. The best metal detectorists in the country were here, swinging, showing off. Many were retirees, many in particular were retired cops and sheriffs. A few of them worked for themselves. One wrote guides to ghost towns. Some worked for “the city”—Tucson, Little Rock, Plainfield. Metal detectorists hunt in Churchyards, Schoolyards, Playgrounds, Fairgrounds, Picnic Areas, Old Military Bases/Training Grounds, Swimming Areas such as Lakes and Rivers, Seaside Beaches, and Sand, Dirt or Grassy Parking Areas. Here, in Oklahoma, they were preparing to hunt among pines ringing a field with an old sand volleyball court at its center. Here, the hills crumpled up into mountains and the roads were slick in places with armadillo and deer and possum blood, the carcasses bloated on the asphalt shoulders. Here we stood in the old campground, the Kiamichi River moving in the dark somewhere beyond where we stood holding our metal detectors in the air. If we put them to the ground they would cry out about power lines, pull tabs, crushed cans, and maybe the treasure Keith had planted. Keith had not yet put his lips to the bullhorn. He had not yet gotten on his ATV and thrown metal into the air with wanton abandon, treasure that landed in the pine needles, joining the buried coins in invisibility. “Pitch black” here had a different meaning; pitch, dark, was once sapped from the pines here, and turned to turpentine. Under the layers of bark, the sap moved, now, untapped. Money coursing beneath a thin surface.

×

On metal detectors’ reading screens, gold and pull tabs look exactly alike—the same portion of the screen throbs with activity, and a rich beep sounds. “What’s a pull tab?” I asked as we waited to start, and the men looked at me with real pity. “Those little metal bits that pry open sodapop cans,” someone said. The tabs we wheedled back and forth as kids, muttering the alphabet, and when the tab came off on the letter P we’d know Payton was our future husband, and we’d toss the pull tab somewhere to get slowly covered not in dirt, really, but in a dense mixture called soil, which is a combination of dirt, hair, dead skin, bones, pebbles, dog shit, our shit, bug shit, bugs, fragments and flakes of larger things we never think to imagine. Metal detectorists talk about how their machines “discriminate” between things, beeping one way to sound for nickel, beeping another way to sound for copper. But between gold and tin there is no discrimination.

Pull tabs are what detectorists find more frequently than any other thing. Even the cans that they were once attached to are, by comparison, rare. Some men hang their framed collections of pull tabs in what they themselves call their man-caves. Like glittering aquifers, pull tabs run under most of the ground of the U.S., now, under the map, the evidence of old refreshment, the root of diabetes, small, shiny, slippery, fish-like trash.

Detectorists often compare their hobby to fishing. Like fishing, they say, you need patience. Swinging the machine over a field for ten hours has, they say, a similarly meditative quality to standing in a river and casting, waiting. But the objects detectorists catch and reel in are not alive, though they often claim they are, that a man can feel the past simply by holding the discovery in his hand. A Spanish reale, an Indian head penny, a class ring. They are objects once owned by other people.

Other similes: detectorists—and the majority are men—look like those yellow-vested pesticide applicators on the side of the highway. They sound, en masse, and I have really only watched them en masse, like an orchestra pit tuning up, but an orchestra of solely electronic instruments. They sound like a group of geriatrics with simultaneously malfunctioning hearing aids, shrieking at different piercing pitches (a simile which, actually, holds real truth to it, because many of these men at the campground were elderly, and could not hear the shrill noises of their detectors, and swung their machines with an impotent intent, kneeling to dig with seemingly random bursts of certainty). It was the possibility of gold in trash, the potential treasure every time they dropped to their knee, as if proposing every two minutes (each man wore a knee pad for this purpose on his “drop knee,” which allowed him to kneel repeatedly to dig), that kept them going. Simile, maddening, keeps detectorists hunting. For in it, somewhere, out of view, an authenticity itches and shines.

One man, speaking for all, remembered aloud, in the pines, the first gold coin he found: “It was yellow. I was on my knees in an old picnic grove. I turned around and looked to see if anyone was watching.”

×

Earlier that day, a contingent of gold prospectors from Texas headed down to the Kiamichi River, which choked with some sort of mallow.

I watched with the snakes between us, from a short bluff above the bank. Were they contemporary miners, these men? Scavengers? Raiders? The prospectors seemed different from the detectorists, their greed more bald, more blazing. They seemed less interested in the past, though some of them occasionally used “historical” methods of panning when they got tired of vacuuming the river.

Beyond me, behind me, a group of men moved their instruments across the ground. They didn’t know what they were searching for. That was the difference. When they found it, though, they existed alongside a woman from 1923 who, shaking a picnic blanket out, accidentally flung her wedding ring off into a pile of leaves, folded the blanket up, placed it in the back of the car, and motored off with her family before realizing the thing was gone. There is no map for these types of discoveries, though sometimes detectorists input the GPS coordinates of their finds into a database, as if there could be a meaningful or predictable pattern to the times and places we lose things.

×

The rule here was finders keepers. A man named Tim cited a recent example of Boy Scouts cleaning up a vacant city lot somewhere in Texas. The boys found a box full of gold coins—I didn’t interrupt to mention how unlikely this seemed—and the city laid claim. The past owner of the lot said no, it belonged to him. “We feel the Boy Scouts deserve it,” said Tim, who used to be a Boy Scout. “They found it. There’s always going to be someone else claiming your treasure.”

×

“You see that shirt?” Mark, in a lawn chair, staring at someone’s back (“Texas Will Again Lift Its Head and Be Among the Nations: Secession!”), muttered that morning. “I’m from Missouri. I’m just like, ‘Whoa. You really think that? Secession?’ I build waterfalls. I put clear crystals in the waterfalls. Why do I do it? I always wanted to do it, so I just did it. Election years seem like they’re slower than other years. People hold onto their money. They get, like, scared or something. They don’t make time for extravagance, for landscapes.” Mark had the wildly mystified eyes of an old Adam Sandler character. “I feel like I’m missing something,” he said, his tanned turtle’s neck holding his lovely spooked face, his hand bearing a titanium wedding ring and tracing in the air the shape of far-off water, “If the river drops and I’m not out there.” The Missouri River, right outside the door of his house back in St. Charles, Missouri. I pictured it long and gray, visible from his dark kitchen window. Between building waterfalls he goes down to the river three times a week to search not with his detector but with his eyes and hands, for arrowheads, bones, pottery, anything old that the water, moving, dropping, rushing, and the gravel, turning, grating, bumping, pushes up. Back to his eyes; they were an odd blue, with wet lashes, as if he was leaking, and they stared out towards the fire, attracted to light. They did not look at me. “I have a big room, a plate of mammoth teeth. I like old bottles. I have a Hiram Bigelow’s Kickapoo Indian Cough Cure. I have a Great Doctor Kilmer’s Swamp Rust Kidney Liver Bladder Cure. You can tell how old bottles are by where the seam stops. I have bone awls. The Mississippian Period is my favorite. I have a bird-head rooster-head rattle. I shake it and it rattles. I have three Clovis points. I have lots of Daltons. I have mammoth teeth, camel teeth, and a giant sloth leg bone. I have twenty-three hundred arrowheads from creeks, rivers, and caves. Thirty-six years I’ve been collecting. I have a human head effigy gorget. I have a clay earspool from right where the Missouri and the Mississippi come together.”

Months later, I would sit behind Mark as he steered a tin-roofed boat down the Missouri River, in the direction of this confluence. We anchored in the brackish shallows off the edge of an island, or gravel bar, really, that is sometimes underwater, and which Mark made me promise never to name. He carried me to shore on his back.

×

It was Jo Ann’s metal detector that I held in the pitch dark. The only woman besides me in the group—detectors in the air, waiting to sound, to rustle in the needles, to grapple for the thin cold dime, or ring, or whatever treasures Keith had thrown to the ground—Jo Ann dropped a penny in front of us in the pitch black and told me to practice. I lowered my detector and swung it over the spot I thought the coin landed. A beep, low, then a beep, high. Reaching for it for minutes, aching for the cold little thing, sifting pine needles blindly through my hands, I found I couldn’t find it. It was embarrassing. It should have been there, right in front of me. The men warbled softly around us, waiting to start the hunt. Keith’s ATV revved up. When I stood, penniless, Jo Ann’s head turned to me with the peering intent of a lover. The smell of pines was strong, encouraged by the warm night air. “Lucy,” she asked. “Have you found Jesus?”

×

Treasure is everywhere, running under our feet amidst slippery pull tabs severed from their original soda cans. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Americans search for it, however they define it, and they do have startlingly varied definitions of worth. Some Iowans collect geodes, many Midwesterners collect arrowheads, Southerners and Northerners both dig for Civil War bullets and buttons, everyone loves crockery, and most certainly everyone wants gold. In moments of economic distress, we hunt further and harder for what we believe is there, somewhere, outwards away from us. Like religion, treasure hunting follows, often, on the heels of desperation—though for spiritual or economic needs I’m not sure. Just after the Revolutionary War, in a region of upstate New York known as the “Burned Over District” for how thoroughly it had been ignited by various religious movements and leaders, exhausted people formed “money-digging companies” and a young Joseph Smith spoke of how, in the summer, chests of money “bloomed” to the surface of the soil. Divining, a new word, found water, gold, angels in the dirt. Coin collecting became popular only during the Great Depression—it let us amass valuables, certainly, but also evidence of another time’s flushness, pieces of metal that jangled, once, in some other person’s pocket. Humans used to hide money in pots and bury the pots under trees, one of the many retired deputies told me. “We didn’t trust banks. So pot hunters came around”—people who searched under trees, in back gardens, in the places outside that we learned to hide our things of value.

×

Not far away from here, a little less than a hundred years before, some men also hunted. Except instead of planting coins and rummaging through the needles to find them in the dark, or waiting for Keith to bellow DETECTORS DOWN!, commencing a hunt for a set of skeleton keys that would unlock little treasure chests he bought in the Wal-Mart toy aisle, six men formed the Pocolo Mining Company in 1933 in order to raid what would become the “King Tut’s Tomb of North America”: the Mississippian Culture’s burial mounds at Spiro, just two hours away from Antlers. The resultant local antiquities trade, which funneled items into the Smithsonian and museums across the country, operated out of Antlers.

Did the detectorists know about these six men, who during the Depression leased the pre-Columbian mounds from a poor African-Choctaw family? For decades before, men that the locals called “pot hunters” had been visiting the mounds at night, digging quickly, snatching shards, pipes, items chilled for centuries in the earth. These six in particular, the Pocolo Mining Company, had connections with relic dealers. They had cased the land like Larry did for me, hand to brow: “How can you tell there’s an Indian site there? Because there’s something different. You see where that little knoll was? You know there’s a tent or a midden there, and if there was a midden, which was where they buried a lot of their stuff, you go over there and you kick the top of the ground and you see flint where they went ahead and chipped arrowheads.” Thoreau talked this way. So did Jimmy Carter, who wrote a loophole into the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 so that hunters could continue to collect arrowheads off the surface of the soil.

Within minutes of beginning to dig, the six men found “hundreds of…skeletons, lying in pockets sometimes three and four deep.” There too: pipes from five to thirty-one inches long, and copper needles, and ear spools, and feathers, and maces, and baskets, and cloth, and beads, and arrowheads, and conch shells. They flooded the market.

×

There are dangers to reading maps on top of each other. Doing so is claiming the realities of the older map have vanished, that you need a legend, a newer map, to see what was there before. In reality, things live on. George Stewart’s Names on the Land reminds us that “since names—corrupted, transferred, re-made—outlive men and nations and languages, it may even be that we still speak daily some name which first meant ‘Saber-tooth Cave’ or ‘Where-we-killed-the-ground-sloth.’”

The Mississippian Culture made the mounds, the Caddo Indians were their descendants. Only later, centuries later, did the Choctaw move here, forced to Oklahoma along a route I criss-crossed in my car, imagining people walking the highway. But that contemporary paved line is too straight. It is not a reflection of the Trail of Tears. It is not even like it.

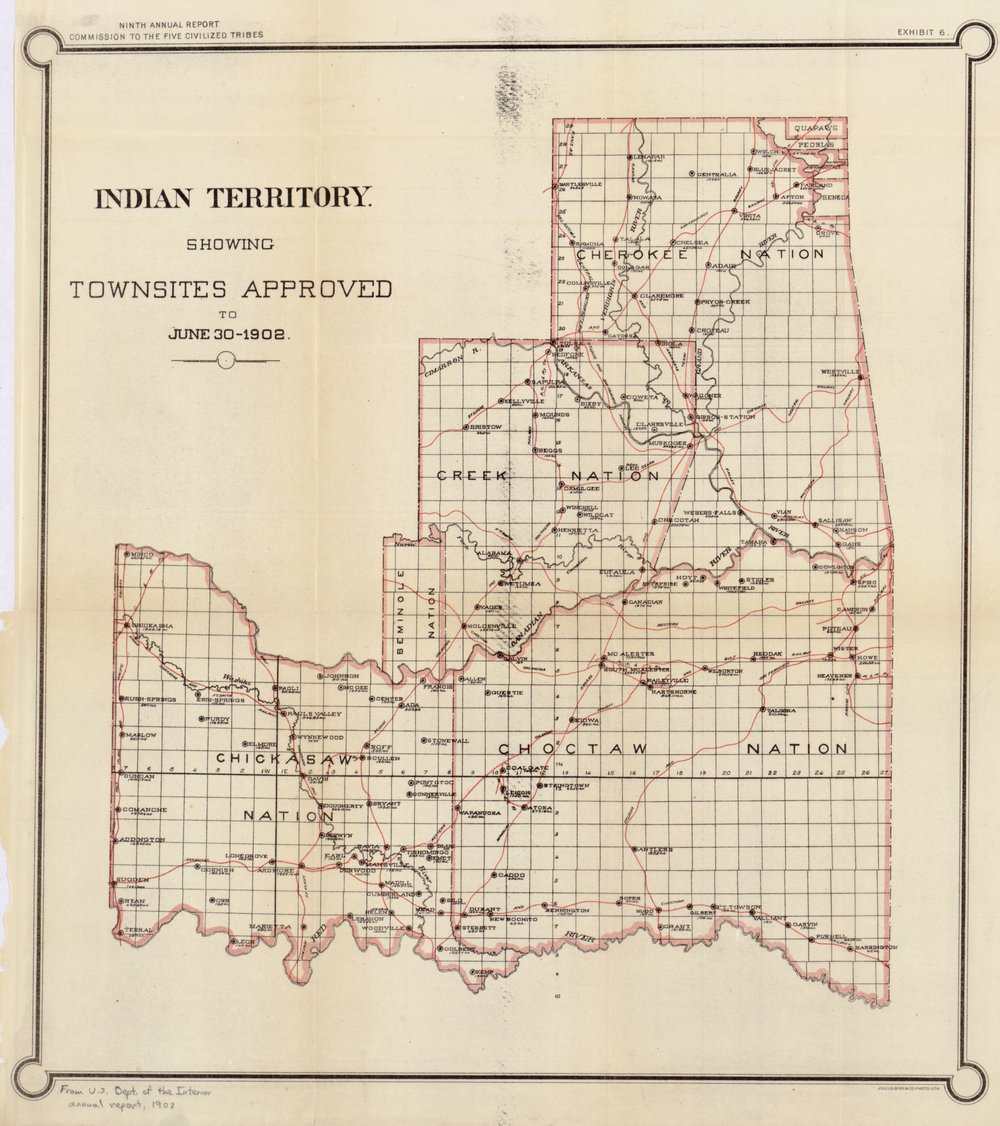

Oklahoma became a state in 1907. On the map from 1902, Antlers sits relatively alone on the grid, with an allotment of 182.5 acres for its township. The mapping came on the heels of the Dawes Act, which abolished tribal land titles, paving the way for statehood.

Oklahoma became a state in 1907. On the map from 1902, Antlers sits relatively alone on the grid, with an allotment of 182.5 acres for its township. The mapping came on the heels of the Dawes Act, which abolished tribal land titles, paving the way for statehood.

×

“No one understood what was coming from here. When you dig up stuff you erase its context completely. All these museums are full of stuff from Spiro that they have no idea how to classify,” Dennis Peterson said. He is the sole staff member at the site, which has been gutted by the state budget. He can no longer walk outside to show people the mounds; they must walk themselves. He must stay behind the desk selling t-shirts and postcards. In the Spiro Mounds newsletter, he asked for readers’ prayers.

Over 25,000 prehistoric sites are known of in Oklahoma at this time spanning over 20,000 prehistoric years of occupation but the only prehistoric, Native American, archeological site in Oklahoma that people can visit is the Spiro Mounds. Unlike the forts, the land run, even the removal period, there is a significant lack of movies and popular books about our earliest history, which means that most people have little, no, or a wrong vision of what most of our past is like. While museums and private collections have artifacts on shelves like stone tools and pottery, they are seldom seen by visitors as representing people, instead seen as curious to be collected like one would collect coins. (Spiro Mounds Newsletter, 2016)

The looting of the Spiro Mounds prompted Oklahoma’s passing of the Antiquity Protection Law in 1935, one of the first such laws in the country. But by then, said Dennis, “commercial diggers and buyers [had] distributed the artifacts in massive amounts. People were buying up stuff from other sites, they were making their own artifacts…caveat emptor was very much in place.” At academic conferences today, men will approach Dennis and show him the trunks of their cars, filled with engraved conch shells for which they paid thousands of dollars. They are usually fake.

Dennis extended his hand to me and in it was a key, silver, small, to the Spiro Mound Archaeological Site’s lone golf cart. “It’s better,” he said, “than walking.” I had not met the metal detectorists yet in Antlers. They would all, each of them, tell me about how frustrating it is to find artifacts and donate them to museums, then never see them displayed. “It’s not even worth it,” they would tell me.

At Spiro, I was the only one, and I was in the golf cart.

×

They have found, they told me, a woman’s ring studded with emeralds, a woman’s diamond ring, a woman’s gold ring, a class ring, a gold coin (they always remember the first one), a very fancy cellular phone (the girl who lost it thought the detectorist wanted “ransom money”), two skeletons dressed in armor and chain mail (Spanish soldiers, donated to the Oklahoma Historical Society), quarters (in the ground in front of a laundromat), a cache of old coins sprayed out in the soil, broken Mason jar nearby, as if someone stole and then dropped it, clay marbles, clay earspools, pottery shards, arrowheads, mammoth teeth, a diamond ring, and many things they cannot tell me, except then they did begin to tell me.

They are using modern technology, they said, infrared and the Internet, and they had connections with the right buyers who—once the men find their various treasures, and the treasures are all over, of all kinds, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, British, Native—will find dark little channels in which to sell them. Or not. Many men just keep their finds, for fear of getting caught, or because they can’t figure out who to sell them to, or because they don’t want to. If they feel like it, they will donate to museums, though this is somewhat rare. Their finds are framed; they hang in man caves, or sit behind glass in living rooms, or hide in shoeboxes in their closets. They all had collections, some that they like to show off, some that they don’t.

×

They hunt Construction Sites, Abandoned Gas Stations, Old Neighborhood Boulevards, Old Inns and Bed & Breakfasts, Ghost Towns, Outdoor Flea Markets, Tent Revival Meeting Areas, Under Bridges, Walking Paths/Hiking Trails, Orchards, Stone Walls/Fences, Railroad Tracks/Stations/Stops, Rodeo Arenas, Mining Camps, Taverns, Highway Lookout Sites, College/University Campuses, Old Dance Sites, and Lover’s Lanes.

×

The men plus Jo Ann gathered here in Antlers and have gathered here for eighteen years every fall, for these “planted” hunts in which they might win a new detector, microwave, whatever.

×

When Keith shouted through the bullhorn that we could start, I lowered Jo Ann’s detector and stood next to her, sweeping the ground I couldn’t see, hearing the pine needles yield, feeling the movements of the men around us as they swung rapidly and then kneeled to rummage blindly for the treasure. The machine stuttered occasionally, yelped. We hunted for an hour this way, the ground, our backs, struck only by the moon. It smelled of sweat. The men began to jingle as they walked and swung. You could imagine turpentine in the pines if you wanted to. The treasure, we all knew, was here. I found nothing.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Lucy Schiller is an essayist whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Essay Review, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in Iowa City and is at work on a book about treasure hunting in the American West.

32.930238, -117.260277

The first metal detectorists I saw were men searching the beach of my childhood home in Southern California. They were looking for recently lost valuables, though I had no idea of that, as a kid. I remember it being foggy, and that they would walk the beach for hours, searching, and that some relative of mine called them vultures. I liked them more than the surfers, who I once saw (maybe I'm misremembering) surf down the sloped body of a beaching whale near death. I wanted a metal detector.