101 Oak Street

35°12'9.13"N

83°49'23.12"W

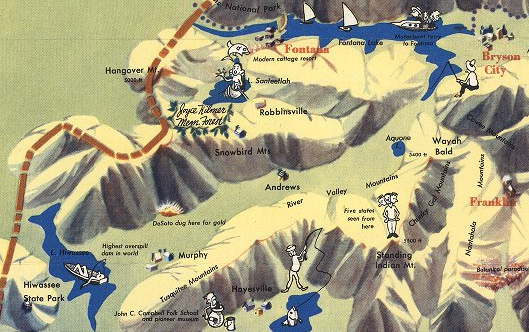

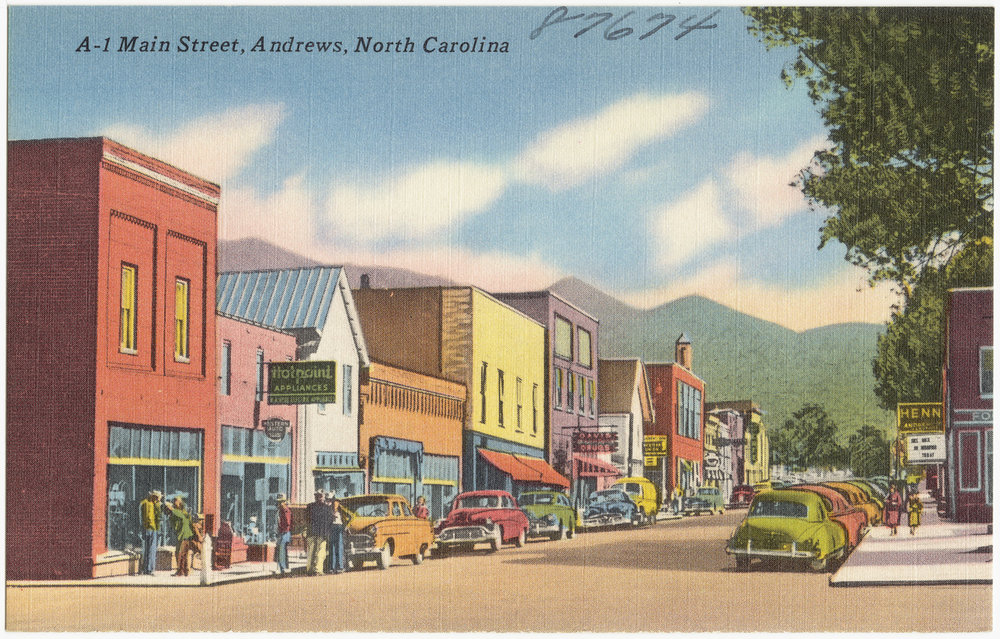

Once upon a time, there was a defense lawyer who was a member of the little church my family attended—a man who became a frequent visitor to our home. The defense lawyer was a few years younger than my parents—a big guy, but not fat, not skinny, not muscular. Just big, imposing, and strong. To be in a room with the defense lawyer was to experience the absolute fullness of his presence, which was embodied by the sonorous, rhythmic beat of his voice. The defense lawyer had survived polio as a child, and now with one bad leg limped with gusto through life, the motion of which caused his bangs to flop against his forehead. I’d known him most of my life and admired his sense of humor, which was brash and irreverent and cocky. He was the kind of guy who knew how to interact with kids, who paid them the kind of attention they loved, meaning that he knew how to be warmly adversarial. He seemed to legitimately enjoy making fun of me, and because he was smart and funny and ruthless, he made making fun of me fun for me. He got a kick out of reminding me about the time, for instance, that he flicked me, hard, on the knuckles. This had happened one evening when he’d stopped by, as he often did, for Friday night supper: I’d been banging on the piano and my mother, who had been in the kitchen preparing our food, yelled at me to stop, but like all juvenile dingbats who’d rather continue doing what they wanted to do instead of obeying their parents, I kept playing, who knows why, maybe because once I started a song, even as one as poorly composed as mine most likely was, I had a very strong compulsion to finish it, and so the defense lawyer, who was sitting on a nearby couch, reached over and flicked one of my hands, right on the knuckle. It surprised me, and it stung. It really hurt, actually, and this was part of the surprise: that a simple flick—like some kind of jujitsu technique the defense lawyer had, over the years, come to master—could inflict real pain. For a second, maybe a little while longer than a second, I resented him, in the way that I resented all adults who weren’t my parents when they attempted to discipline me, but the defense lawyer just laughed when I said “Hey, what’d you do that for?” and threatened to flick me again if I continued to disobey my mother’s instructions.  Pouting, I slunk away, which made him laugh. Of course, I couldn’t hate him forever, partly because he was a great storyteller who told stories about what it was like to grow up in Michigan, a repertoire that included a story about how the boy’s dean—now a retired pastor who led lively song services at our church—had cried when he’d found the defense lawyer and his friends playing cards on the Sabbath, and partly because it was the defense lawyer who would soon introduce me to the son of a woman the defense lawyer happened to be dating, a boy who would become, as the defense lawyer had predicted, my best friend. I’d heard about this boy long before I met him. The defense lawyer had assured me that we would get along great; after all, as he put it, we both “played with dolls.” This was, as you might imagine, an assertion with which I took issue. The G. I. Joe figures I collected were not “dolls.” They were “action figures.” The defense lawyer disagreed. “So tell me,” he’d say, “These little men you play with. They’re not real, are they? They’re little replicas of people, right? Isn’t that what a doll is? So by definition, you’d have to admit that your little man there could be classified as a doll, right?” (The defense lawyer said, “Right?” a lot. It was a thing he did almost every time he made any kind of claim, which had the effect of making him seem both hesitant and assertive.) One Saturday, the defense lawyer brought his girlfriend and his girlfriend’s kids to church. My best-friend-to-be showed up for Sabbath School—which was exactly like Sunday School only it happened on Saturdays—and in the room where my age group met, on a shelf in a closet, there was a box, a yellow cardboard container that, as far as I can remember, was used to collect money for some cause or other, probably something to do with evangelistic efforts or disaster relief or a mission field. My friend-to-be pointed at the box and immediately laughed and said, “Who is that gayblade?” I’d never heard anyone use the word “gayblade,” had no idea what it meant, only that it was most certainly derogatory and therefore did not belong in a Sabbath School classroom, where we would soon sing songs about loving Jesus and going to Heaven and hear stories about boys and girls doing good deeds or learning their lessons forevermore. I liked this boy immediately, which meant, of course, that the defense lawyer’s prophecy had come true. The boy and I became instant friends, playing with our action figures and drawing comic books and riding our bikes through town and getting called “skaters” because of our quasi-angular haircuts. I started to visit the boy’s house—a little white farmhouse with a green roof, whose address was 101 Oak Street. There was something quintessentially wholesome—if not downright American—even then, about a street named “Oak,” something classical about the designation “101,” a number that the defense lawyer’s girlfriend had chosen herself. Because once upon a time, the house had no number. It had no mailbox, which was fine, because the family lived within walking distance of the post office. Still, my friend’s mother must have decided that houses were incomplete without a numeral signifying their place on the street, so she selected the digits from metal rungs at the Builder’s Supply where, incidentally, she worked as a secretary, and nailed them to the front wall of the white, green-roofed structure where she and her kids lived, a house from whose windows you could see distant, pale blue mountains. I loved this house from the moment I met it, partly because it wasn’t mine and almost all houses that weren’t mine were somehow mysterious and exotic, especially those that were in actual neighborhoods, unlike mine, which sat at the bottom of a mountain on a little hill above two streams, and partly because it was the house where my friend lived: a goofy, bespectacled kid with a penchant for Chef-Boy-R-Dee and toaster waffles and Intellevision and the Chicago Cubs. I loved it because it sat exactly one block away from Main Street in my hometown—a sad little grid of decaying brick buildings—which meant that my friend and his sister—a brunette who, though she was younger, was taller and who also enjoyed mocking the residents of our town using our own versions of their countrified twang—could exit their house and within minutes be inside the Piggly Wiggly, where a vast array of treats—chewing gum, candy, MAD magazines—awaited us. And so, in no long time at all, the house at 101 Oak Street became my favorite destination, even if visiting it involved a ride on my bike that my mother wasn’t crazy about, since doing so involved the navigation of windy back roads and crossing the four lane highway that ribboned through the heart of our valley, and drivers could be crazy plus my mom knew my friend’s mother and the defense lawyer weren’t always around, and that the boy and I and his sister would often have free reign of the house, and the idea of three kids playing without any “supervision” unnerved her. What she didn’t know—and what my friend’s mother and the defense lawyer kept absolutely secret—was that when the couple would say they had to run an errand, they would steal away for hours at a time to the man’s cabin at the top of a nearby ridge—another exotic home that was, I knew, full of objects that invited introspection and pulsed with mystery: toothy geodes—like the cracked open eggs of dragons—from the American southwest; a drawing, hung on the kitchen wall, of Jesus, whose closed eyes popped open if you stared long enough; a secret wall safe behind a tapestry; a wall-hung sword; a dead flying squirrel (which lived in the freezer); and the defense lawyer’s record collection, which included the melancholy compositions of new age harpist Andreas Vollenwieder and the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album (my friend and I would look for Aliester Crowley on the cover because we’d both read a book called Rock’s Hidden Persuader, which had exposed various bands’ attempts at so-called “back-masking,” and the idea of musicians inserting secret backwards messages into their songs fascinated us). There, at this cabin, the defense lawyer and his girlfriend would smoke pot and have sex, and though neither of these activities seem especially scandalous to me now, back then the notion that the defense lawyer and my friend’s mother had escaped so that they could fuck and do drugs would’ve absolutely blown our sweet little minds. We were good kids, after all, and my friend was far better than I ever wanted to be, meaning that he was more conscientious, and nearly impossible to tempt, and exceptionally stubborn in his refusal to break rules—especially those set by his mother. Aside from showing me a Playboy that had been stashed—presumably by the defense lawyer, but who knows—in his mother’s closet, I remember my friend acting as our collective conscience, saying, if I suggested we should treat ourselves to another Little Debbie, that, “No, mom wouldn’t want that,” a phrase that, as soon as he uttered it, indicated that whatever plan I had to break whatever rule I’d proposed we break was now as good as dead. And so, and in these ways, 101 Oak Street became my second home. It was the place where we ate grilled cheese sandwiches in the wooden booth of a breakfast nook and listened to a silver boom box that played cassettes of Hall & Oates and Michael Jackson and the Beatles and 10,000 Maniacs, stuff my parents would have never played because they didn’t listen to rock, only gospel and easy listening. A place where my friend and I held our breath whenever the defense lawyer’s boxer—who spent most of her time in this house—emitted her silent but deadly farts. Where, because I could never master the track pad, I ended up spending hours watching my friend play Intellevision, navigating the mazes of Dungeons and Dragons and shooting arrows at snakes, which, once hit, dispersed into digital mist. Where we watched the defense lawyer’s boxer nurse a litter of puppies and where the defense lawyer knelt down and, taking one of the dog’s wrinkly teats—it looked like a miniature sausage link—between his fingers, he squeezed, thereby lasering a thread of dog milk into his open mouth, for no other reason than to gross us out. Where the house’s single toilet had a wooden lid and on the bathroom wall a photo of 19th century lumberjacks circling a giant redwood with axes and a caption that said, “Small strokes fell great oaks.” Where we watched Cubs games on WGN and laughed at the voice of Harry Caray. Where, outside in the street, we played keep away from the boxer, whose frothing saliva would be-slime the ball we threw. Where we watched MTV and made fun of any singer who took themselves too seriously, especially Bruce Springsteen. Where I’d stand on Saturday mornings, waiting for my friend to get dressed in the light of Transformers or He-Man, the forbidden shows of Saturday morning, shows I had never before seen, not on Saturday, a day that the majority of American kids, I knew, spent glazed by the lurid glow of Hanna-Barbera cartoons, slurping milk sugared by the same rainbow-colored cereals that were advertised during the toon’s commercial breaks.

Pouting, I slunk away, which made him laugh. Of course, I couldn’t hate him forever, partly because he was a great storyteller who told stories about what it was like to grow up in Michigan, a repertoire that included a story about how the boy’s dean—now a retired pastor who led lively song services at our church—had cried when he’d found the defense lawyer and his friends playing cards on the Sabbath, and partly because it was the defense lawyer who would soon introduce me to the son of a woman the defense lawyer happened to be dating, a boy who would become, as the defense lawyer had predicted, my best friend. I’d heard about this boy long before I met him. The defense lawyer had assured me that we would get along great; after all, as he put it, we both “played with dolls.” This was, as you might imagine, an assertion with which I took issue. The G. I. Joe figures I collected were not “dolls.” They were “action figures.” The defense lawyer disagreed. “So tell me,” he’d say, “These little men you play with. They’re not real, are they? They’re little replicas of people, right? Isn’t that what a doll is? So by definition, you’d have to admit that your little man there could be classified as a doll, right?” (The defense lawyer said, “Right?” a lot. It was a thing he did almost every time he made any kind of claim, which had the effect of making him seem both hesitant and assertive.) One Saturday, the defense lawyer brought his girlfriend and his girlfriend’s kids to church. My best-friend-to-be showed up for Sabbath School—which was exactly like Sunday School only it happened on Saturdays—and in the room where my age group met, on a shelf in a closet, there was a box, a yellow cardboard container that, as far as I can remember, was used to collect money for some cause or other, probably something to do with evangelistic efforts or disaster relief or a mission field. My friend-to-be pointed at the box and immediately laughed and said, “Who is that gayblade?” I’d never heard anyone use the word “gayblade,” had no idea what it meant, only that it was most certainly derogatory and therefore did not belong in a Sabbath School classroom, where we would soon sing songs about loving Jesus and going to Heaven and hear stories about boys and girls doing good deeds or learning their lessons forevermore. I liked this boy immediately, which meant, of course, that the defense lawyer’s prophecy had come true. The boy and I became instant friends, playing with our action figures and drawing comic books and riding our bikes through town and getting called “skaters” because of our quasi-angular haircuts. I started to visit the boy’s house—a little white farmhouse with a green roof, whose address was 101 Oak Street. There was something quintessentially wholesome—if not downright American—even then, about a street named “Oak,” something classical about the designation “101,” a number that the defense lawyer’s girlfriend had chosen herself. Because once upon a time, the house had no number. It had no mailbox, which was fine, because the family lived within walking distance of the post office. Still, my friend’s mother must have decided that houses were incomplete without a numeral signifying their place on the street, so she selected the digits from metal rungs at the Builder’s Supply where, incidentally, she worked as a secretary, and nailed them to the front wall of the white, green-roofed structure where she and her kids lived, a house from whose windows you could see distant, pale blue mountains. I loved this house from the moment I met it, partly because it wasn’t mine and almost all houses that weren’t mine were somehow mysterious and exotic, especially those that were in actual neighborhoods, unlike mine, which sat at the bottom of a mountain on a little hill above two streams, and partly because it was the house where my friend lived: a goofy, bespectacled kid with a penchant for Chef-Boy-R-Dee and toaster waffles and Intellevision and the Chicago Cubs. I loved it because it sat exactly one block away from Main Street in my hometown—a sad little grid of decaying brick buildings—which meant that my friend and his sister—a brunette who, though she was younger, was taller and who also enjoyed mocking the residents of our town using our own versions of their countrified twang—could exit their house and within minutes be inside the Piggly Wiggly, where a vast array of treats—chewing gum, candy, MAD magazines—awaited us. And so, in no long time at all, the house at 101 Oak Street became my favorite destination, even if visiting it involved a ride on my bike that my mother wasn’t crazy about, since doing so involved the navigation of windy back roads and crossing the four lane highway that ribboned through the heart of our valley, and drivers could be crazy plus my mom knew my friend’s mother and the defense lawyer weren’t always around, and that the boy and I and his sister would often have free reign of the house, and the idea of three kids playing without any “supervision” unnerved her. What she didn’t know—and what my friend’s mother and the defense lawyer kept absolutely secret—was that when the couple would say they had to run an errand, they would steal away for hours at a time to the man’s cabin at the top of a nearby ridge—another exotic home that was, I knew, full of objects that invited introspection and pulsed with mystery: toothy geodes—like the cracked open eggs of dragons—from the American southwest; a drawing, hung on the kitchen wall, of Jesus, whose closed eyes popped open if you stared long enough; a secret wall safe behind a tapestry; a wall-hung sword; a dead flying squirrel (which lived in the freezer); and the defense lawyer’s record collection, which included the melancholy compositions of new age harpist Andreas Vollenwieder and the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album (my friend and I would look for Aliester Crowley on the cover because we’d both read a book called Rock’s Hidden Persuader, which had exposed various bands’ attempts at so-called “back-masking,” and the idea of musicians inserting secret backwards messages into their songs fascinated us). There, at this cabin, the defense lawyer and his girlfriend would smoke pot and have sex, and though neither of these activities seem especially scandalous to me now, back then the notion that the defense lawyer and my friend’s mother had escaped so that they could fuck and do drugs would’ve absolutely blown our sweet little minds. We were good kids, after all, and my friend was far better than I ever wanted to be, meaning that he was more conscientious, and nearly impossible to tempt, and exceptionally stubborn in his refusal to break rules—especially those set by his mother. Aside from showing me a Playboy that had been stashed—presumably by the defense lawyer, but who knows—in his mother’s closet, I remember my friend acting as our collective conscience, saying, if I suggested we should treat ourselves to another Little Debbie, that, “No, mom wouldn’t want that,” a phrase that, as soon as he uttered it, indicated that whatever plan I had to break whatever rule I’d proposed we break was now as good as dead. And so, and in these ways, 101 Oak Street became my second home. It was the place where we ate grilled cheese sandwiches in the wooden booth of a breakfast nook and listened to a silver boom box that played cassettes of Hall & Oates and Michael Jackson and the Beatles and 10,000 Maniacs, stuff my parents would have never played because they didn’t listen to rock, only gospel and easy listening. A place where my friend and I held our breath whenever the defense lawyer’s boxer—who spent most of her time in this house—emitted her silent but deadly farts. Where, because I could never master the track pad, I ended up spending hours watching my friend play Intellevision, navigating the mazes of Dungeons and Dragons and shooting arrows at snakes, which, once hit, dispersed into digital mist. Where we watched the defense lawyer’s boxer nurse a litter of puppies and where the defense lawyer knelt down and, taking one of the dog’s wrinkly teats—it looked like a miniature sausage link—between his fingers, he squeezed, thereby lasering a thread of dog milk into his open mouth, for no other reason than to gross us out. Where the house’s single toilet had a wooden lid and on the bathroom wall a photo of 19th century lumberjacks circling a giant redwood with axes and a caption that said, “Small strokes fell great oaks.” Where we watched Cubs games on WGN and laughed at the voice of Harry Caray. Where, outside in the street, we played keep away from the boxer, whose frothing saliva would be-slime the ball we threw. Where we watched MTV and made fun of any singer who took themselves too seriously, especially Bruce Springsteen. Where I’d stand on Saturday mornings, waiting for my friend to get dressed in the light of Transformers or He-Man, the forbidden shows of Saturday morning, shows I had never before seen, not on Saturday, a day that the majority of American kids, I knew, spent glazed by the lurid glow of Hanna-Barbera cartoons, slurping milk sugared by the same rainbow-colored cereals that were advertised during the toon’s commercial breaks.  Then: to church, where, on the rare occasion we’d be allowed to sit together, we’d crack each other up with the sketches we drew onto the backs of a church bulletin, each taking turns to create an outlandish toon-scape, a veritable Bosch-ian garden of absurdist delight. Or this: us at a sleepover, laughing hysterically at the fart noises we made by squishing our cupped palms underneath our armpits or blowing on the flesh of our forearms, while outside my friend’s window, his mother and the defense lawyer giggled at the thought of us giving ourselves over, so purely, to laughter. Or this, much later, after we’d gone off to college: my friend’s mom and the defense lawyer finally, after eight years of dating, getting married, selling the white farmhouse with the green roof, and moving to Collegedale, Tennessee, home of Southern Missionary College and the Little Debbie factory. And finally: six months after the wedding, a separation, instigated by the defense lawyer, who simply decided to up and leave, and who subsequently filed for divorce. A few years passed, I graduated from boarding school, went to college, graduated, returned home, and needed a job, so I agreed to work for a time for the defense lawyer, who needed someone to fill in so that I could take the place of his secretary on maternity leave, a vivacious blond who dialed phones faster than anyone I’d witnessed previously, and who, before she left, taught me how to type complaints and emergency custody orders that the defense lawyer dictated onto little cassettes. It was around this time that the defense lawyer began corresponding with a woman in California, a woman who was very pretty but, in my estimation, not very bright, and who, in the end, became enamored with the defense lawyer, who asked for her hand in marriage. The two were married very quickly and the woman from California moved into the cabin, whose interior she subsequently and single-handedly transformed, a process that involved the removal of the wall-hung sword and the magic Jesus poster and the glittering toothy geodes, replacing all this with decorative plates and hand-sewn quilts and a portrait of a guardian angel protecting two children as they crossed a rickety bridge in the night. Despite this massively thorough overhaul, the defense lawyer and his new wife did not live in the cabin much longer; eventually, they migrated to the Pacific Northwest, where the defense lawyer became a prosecutor, and then, after a time, a judge. I still talk to my friend—he lives in Finland now, with two kids and a wife who’s pursuing a postdoc in linguistics—but it’s been a long time—over a decade—since I’ve spoken to the defense lawyer. Even so, I have, upon returning to my hometown, visited 101 Oak Street, and am sad to report that the little white farmhouse with a green roof no longer lives at such location. In fact, the house itself is completely gone, as if it somehow vanished, or got up and walked away. Furthermore, absolutely no evidence—no ditch or foundation of any kind—exits to suggest that anything or any human had ever lived there, or that anything I claimed to have experienced in such a house had been anything but a dream: only a green field remains, flush with swishing grass. Which means, of course, that the only people who can still see the house are the ones who have seen it before, and the ones who can see it the best—with the most clarity, and with the pang that accompanies the recollection of a home that has disappeared—no longer live here, and are not likely ever to return.

Then: to church, where, on the rare occasion we’d be allowed to sit together, we’d crack each other up with the sketches we drew onto the backs of a church bulletin, each taking turns to create an outlandish toon-scape, a veritable Bosch-ian garden of absurdist delight. Or this: us at a sleepover, laughing hysterically at the fart noises we made by squishing our cupped palms underneath our armpits or blowing on the flesh of our forearms, while outside my friend’s window, his mother and the defense lawyer giggled at the thought of us giving ourselves over, so purely, to laughter. Or this, much later, after we’d gone off to college: my friend’s mom and the defense lawyer finally, after eight years of dating, getting married, selling the white farmhouse with the green roof, and moving to Collegedale, Tennessee, home of Southern Missionary College and the Little Debbie factory. And finally: six months after the wedding, a separation, instigated by the defense lawyer, who simply decided to up and leave, and who subsequently filed for divorce. A few years passed, I graduated from boarding school, went to college, graduated, returned home, and needed a job, so I agreed to work for a time for the defense lawyer, who needed someone to fill in so that I could take the place of his secretary on maternity leave, a vivacious blond who dialed phones faster than anyone I’d witnessed previously, and who, before she left, taught me how to type complaints and emergency custody orders that the defense lawyer dictated onto little cassettes. It was around this time that the defense lawyer began corresponding with a woman in California, a woman who was very pretty but, in my estimation, not very bright, and who, in the end, became enamored with the defense lawyer, who asked for her hand in marriage. The two were married very quickly and the woman from California moved into the cabin, whose interior she subsequently and single-handedly transformed, a process that involved the removal of the wall-hung sword and the magic Jesus poster and the glittering toothy geodes, replacing all this with decorative plates and hand-sewn quilts and a portrait of a guardian angel protecting two children as they crossed a rickety bridge in the night. Despite this massively thorough overhaul, the defense lawyer and his new wife did not live in the cabin much longer; eventually, they migrated to the Pacific Northwest, where the defense lawyer became a prosecutor, and then, after a time, a judge. I still talk to my friend—he lives in Finland now, with two kids and a wife who’s pursuing a postdoc in linguistics—but it’s been a long time—over a decade—since I’ve spoken to the defense lawyer. Even so, I have, upon returning to my hometown, visited 101 Oak Street, and am sad to report that the little white farmhouse with a green roof no longer lives at such location. In fact, the house itself is completely gone, as if it somehow vanished, or got up and walked away. Furthermore, absolutely no evidence—no ditch or foundation of any kind—exits to suggest that anything or any human had ever lived there, or that anything I claimed to have experienced in such a house had been anything but a dream: only a green field remains, flush with swishing grass. Which means, of course, that the only people who can still see the house are the ones who have seen it before, and the ones who can see it the best—with the most clarity, and with the pang that accompanies the recollection of a home that has disappeared—no longer live here, and are not likely ever to return.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Matthew Vollmer’s next book, Permanent Exhibit, is due from BOA Editions, LTD. in 2018. He teaches at Virginia Tech.

35°13'3.93”N

83°49'40.84"W

The house I grew up in, the house I see in my mind whenever I read a story in which a house appears.