Legend

Twins

Roughly 1 in every 30 births is a pair of twins. Uncommon but not rare, there is an ambivalence to twins. They are outliers but not the other, representatives of a fraught dualism. More than a binary, twins are both one and two, a paradox that often signals a breakdown of reason or an intrusion from an otherworldly force, one that follows its own mercurial rules. In other words, twins are tricksters, agents of ambiguity if not outright chaos, and how we receive this is, fittingly, a mirror of our own preoccupations.

All too often, this means twins are represented as a disturbing glitch in the matrix, something to reject or hide from lest we find ourselves embroiled in their game. Think of the ominous harbinger of the Grady twins in The Shining, beckoning Danny to play with them forever and ever and ever and Danny, hiding his face in his hands. Twins often appear like this, fateful and knowing, here to right a wrong, call in a debt, or otherwise restore balance. Dostoyevsky’s dvoynik arrives in a snowstorm shortly after the strike of midnight, a charming operator who manages to succeed where “our hero” the feckless bureaucrat fails. When The Tethered from Jordan Peele’s Us emerge from their underground, they reveal civilized order is not possible without a complementary chaos, but this isn’t the source of harmony so much as horror. There is a sense that twins shouldn’t exist but here they are, standing right before us.

But fearful rejection is only one way of relating to twins and twins are not only one. There are the wholesome hijinks of The Parent Trap and The Adventures of Mary Kate and Ashley; the infuriation and excitement that Geminis bring into our lives; the wonder and spectacle and pathos reserved for Chang and Eng, the infamous Siamese twins; the beer commercial horniness directed at supermodels like Yvette and Yvonne—the list goes on, and these representations and our reactions to them belie the impossibility of knowing this entity that seems to already know us, often better than we do. This inexorable duality is what draws Territory to Twins. The map is not the territory, but if the territory is only knowable via its many maps, then the difference between the two starts to dissolve. For our eleventh issue, we wanted to explore this tension between doubling and distortion, like and unlike, and the troubling of clean borders.

Hannah Hindley and Maddie Norris do this in their essay “Castor/Pollux” by writing letters to one another that each respond to the same uncaptioned photograph and, of course, their ongoing correspondence. The essay is at once a work of ekphrasis and an examination of self through another. “I watch you do the things that I do, too,” Hindley writes. “We are mirrors after all,” Norris answers back. In Addie Tsai’s “To Your Own [Dead Ringer] Be True,” the line between one and another is blurred even further, Tsai losing her identity to her identical twin: “What would you say, Dear Reader, if I admit to you that even I do not know which one I am?” We are always moving around the edges of the self, it seems, lingering in the knowledge that to look for a reflection is also to look for a distortion. Or, as the speaker puts it in Hilary Plum’s poem “If You Can’t Think One Without the Other, You Can’t Thing One”: “In the mirror was not myself / but a movement along the brink of what I was.”

Other works in the issue play with twin forms. Alex Checkovich’s essay “One Foot in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley” is simultaneously an Oulipean homage and a takeover of Annie Dillard’s “On Foot in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley.” In Shira Dentz’s “Come, Be One With Me,” text folds in on and replicates itself, mirroring the polyhedric shape the work is based on. Oana Avasilichioaei’s piece is a diptych of text and image about a diptych of national identities, Canadian and Romanian. Each line of Jessica Newman’s lyric essay “Another” corresponds to a star in the Gemini constellation and, like the constellation itself, the lines evoke both a great distance and a private intimacy.

In putting together an issue on Twins we are attempting what anthropologist Philip Peek terms a “centrality of liminality” but we are also allowing ourselves to fail at such a unification, letting our intention to map a territory spar with its trickster twin. As Geminis and their inexplicably loyal friends will tell you, things are more fun that way.

-Nick Greer & Thomas Mira y Lopez

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

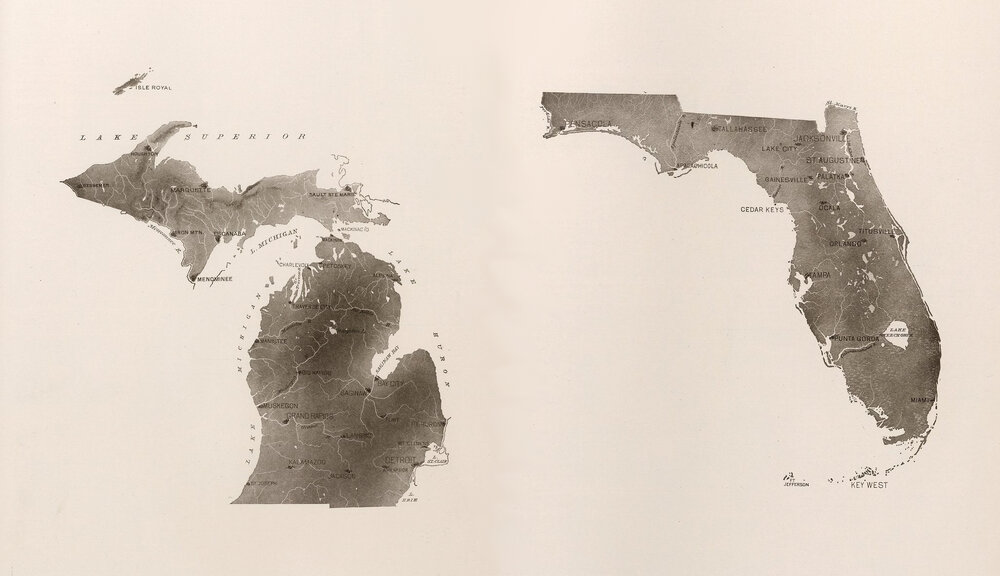

Erik Anderson’s “Dispatches from an Epidemic” is a conjoinment of two relief maps, one depicting Florida and the other Michigan, published by Rand McNally in 1912. The two maps are unmoored, yet also form inversions of one another, not unlike the two voices in Anderson’s piece who speak through and past one another in their attempts to hold onto what’s slipped away. Seen side by side, the maps appear devoid of a wider context—they are here, yet they’re also anywhere—much like the ubiquity of an epidemic.

Erik Anderson’s “Dispatches from an Epidemic” is a conjoinment of two relief maps, one depicting Florida and the other Michigan, published by Rand McNally in 1912. The two maps are unmoored, yet also form inversions of one another, not unlike the two voices in Anderson’s piece who speak through and past one another in their attempts to hold onto what’s slipped away. Seen side by side, the maps appear devoid of a wider context—they are here, yet they’re also anywhere—much like the ubiquity of an epidemic.

||

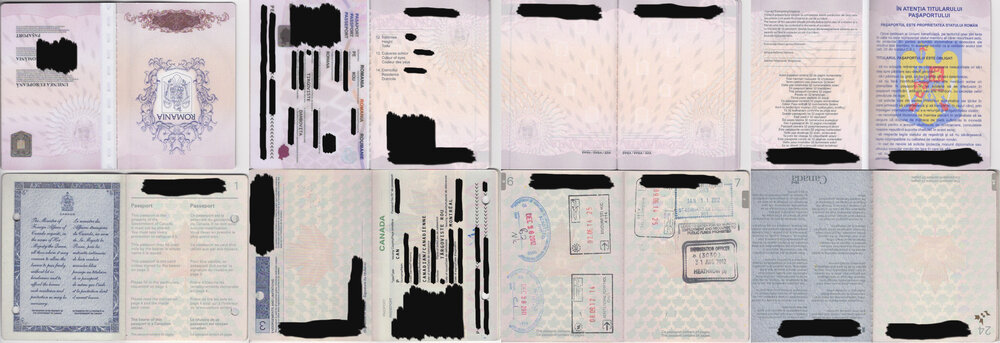

Oana Avasilichioaei's "Citizen Access/Excess" is a diptych of text and image about a diptych of national identities, Canadian and Romanian. The image half of the piece treats these nation’s passports as palimpsests, redacting certain text via blackout. Though dual citizenship suggests an equality or reciprocity, as Oana’s piece observes, they “can never quite be equal.” Romanians in Canada have historically immigrated in waves of political and economic refugees, whereas Canadians in Romania tend to be tourists or expats, beneficiaries of “a high standard of living [and] a comfortable middle-class.” One of Canada’s most celebrated poets of the 20th century, a Romanian immigrant, Irving Layton (née Israel Pincu Lazarovitch), made his mark by writing against Canada’s bourgeoisie and his iconoclasm didn’t soften with age. Accepting the Premio Capri in 1991, Layton rails against “professionalized poets” in his speech, claiming film has eclipsed poetry, but does permit himself a compromised romanticism when he quips that “poetry is your passport out of the hell of consumerism.”

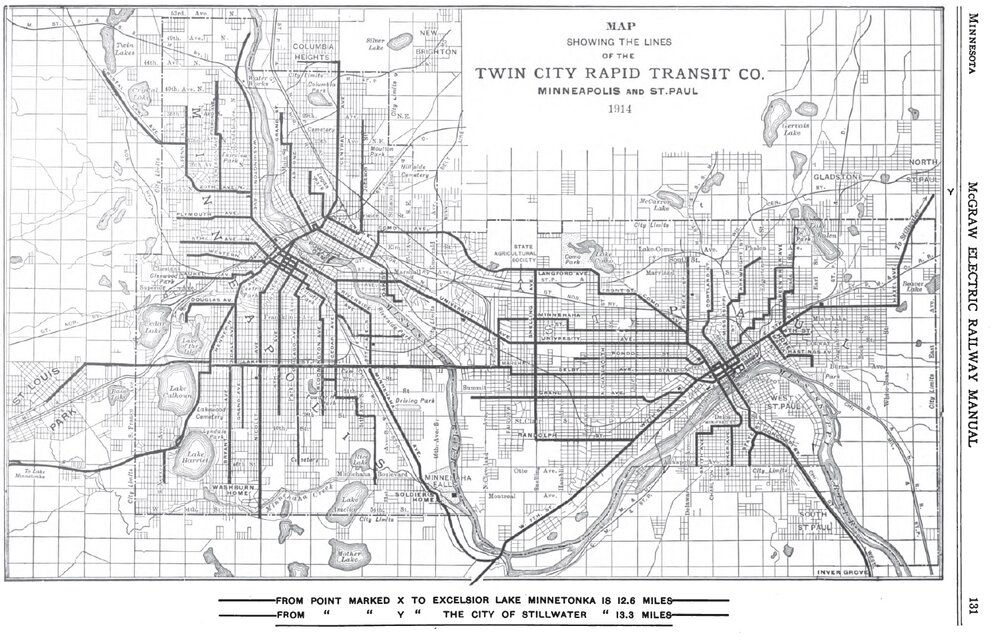

Ryan Ridge & Mel Bosworth’s “May Days” is a collaborative travelogue of bad trips taken in twin cities, whether in name or conurbation or both: The Twin Cities, Twin Falls, Twin Lakes. Though perhaps the most famous twin cities, Minneapolis & St. Paul weren’t the original Twin Cities. This nickname was for Minneapolis & St. Anthony's Falls, a mill settlement on the east side of the Mississippi River that was absorbed into Minneapolis after they were connected by bridge. For a time, the St. Anthony’s Falls area was such an industrial powerhouse, first in lumber then flour, that Minneapolis was known as Mill City before St. Paul’s population doubled from 1915 to 1950, spurred in part by the relocation of Ford’s Minneapolis plant to St. Paul, where it was named the Twin Cities Assembly Plant. This move was motivated by a desire for cheap hydroelectric power, but the scale of Ford’s operations necessitated a dam larger than the existing Meeker Island Lock and Dam upstream, resulting in that dam’s demolition and the construction of Ford Dam (known officially as Lock and Dam No. 1). Though Ford Dam is still in operation, the assembly plant closed in 2011, and the land is currently being converted into a mixed-use real estate development, barring the completion of environmental clean-up efforts. This thoroughness wasn’t afforded to the Meeker Island Lock and Dam, remnants of which can be seen when the Mississippi is low.

Ryan Ridge & Mel Bosworth’s “May Days” is a collaborative travelogue of bad trips taken in twin cities, whether in name or conurbation or both: The Twin Cities, Twin Falls, Twin Lakes. Though perhaps the most famous twin cities, Minneapolis & St. Paul weren’t the original Twin Cities. This nickname was for Minneapolis & St. Anthony's Falls, a mill settlement on the east side of the Mississippi River that was absorbed into Minneapolis after they were connected by bridge. For a time, the St. Anthony’s Falls area was such an industrial powerhouse, first in lumber then flour, that Minneapolis was known as Mill City before St. Paul’s population doubled from 1915 to 1950, spurred in part by the relocation of Ford’s Minneapolis plant to St. Paul, where it was named the Twin Cities Assembly Plant. This move was motivated by a desire for cheap hydroelectric power, but the scale of Ford’s operations necessitated a dam larger than the existing Meeker Island Lock and Dam upstream, resulting in that dam’s demolition and the construction of Ford Dam (known officially as Lock and Dam No. 1). Though Ford Dam is still in operation, the assembly plant closed in 2011, and the land is currently being converted into a mixed-use real estate development, barring the completion of environmental clean-up efforts. This thoroughness wasn’t afforded to the Meeker Island Lock and Dam, remnants of which can be seen when the Mississippi is low.

||

Sammi Bryan’s “Three Bipolar Elegies” tell the story of two sisters sharing the same body and mind. Their bipolarity goes beyond the psychological and the anthropological, the sisters conjoined in a chimera of human psyches and animal morphologies. Physical conjoinment is rare, especially in the absence of human intervention, but there are records of conjoined twins of many species found in natural habitats: snakes, fawns, leopards, and even dolphins. The pair of conjoined bats featured alongside these elegies is one of three such pairs, this one found in 2001 in Brazil beneath a mango tree, dead but its placenta and umbilical still attached, suggesting the bats were stillborn. X-rays revealed that the bats have two separate spinal columns that fuse in the lumbar region, and an ultrasound showed the bats have two separate hearts, but researchers have opted not to proceed with more invasive sampling. Though the researchers admire how “rare and precious” the bats are, the decision is as practical as it is reverent. Using a more destructive sampling technique is a “one-shot deal” and so the bats will be preserved until newer, better technologies are developed.

Sammi Bryan’s “Three Bipolar Elegies” tell the story of two sisters sharing the same body and mind. Their bipolarity goes beyond the psychological and the anthropological, the sisters conjoined in a chimera of human psyches and animal morphologies. Physical conjoinment is rare, especially in the absence of human intervention, but there are records of conjoined twins of many species found in natural habitats: snakes, fawns, leopards, and even dolphins. The pair of conjoined bats featured alongside these elegies is one of three such pairs, this one found in 2001 in Brazil beneath a mango tree, dead but its placenta and umbilical still attached, suggesting the bats were stillborn. X-rays revealed that the bats have two separate spinal columns that fuse in the lumbar region, and an ultrasound showed the bats have two separate hearts, but researchers have opted not to proceed with more invasive sampling. Though the researchers admire how “rare and precious” the bats are, the decision is as practical as it is reverent. Using a more destructive sampling technique is a “one-shot deal” and so the bats will be preserved until newer, better technologies are developed.

||

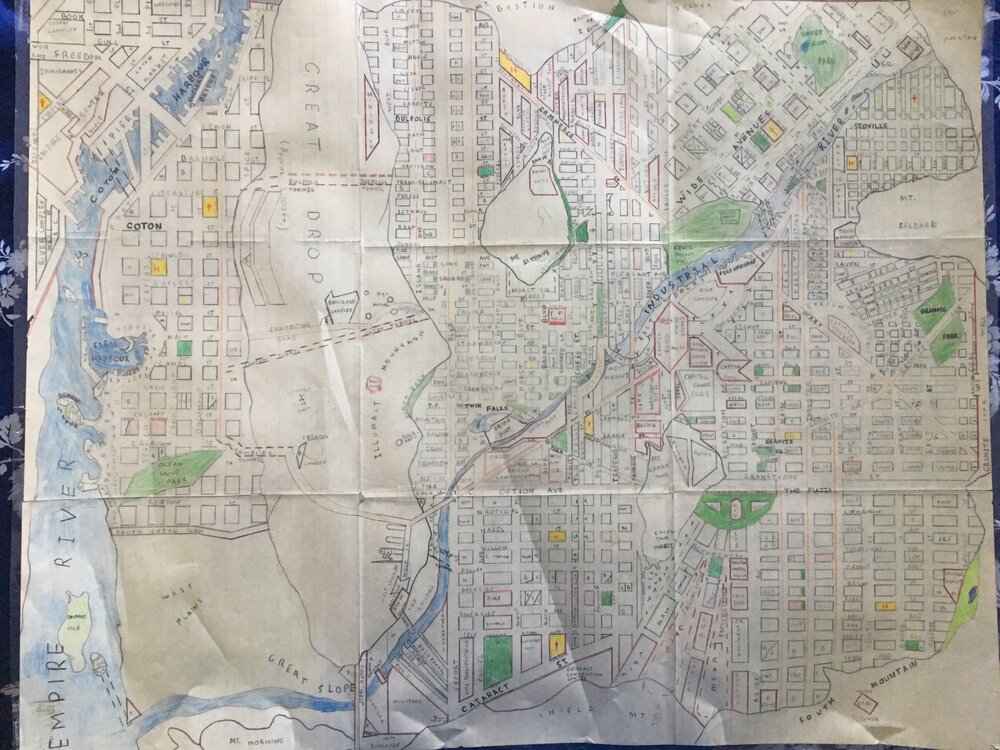

This map is a work of folk art, drafted by my 12- or 13-year-old self in the late 1980s. It depicts “Invinciville,” a city resting inside a crater surrounded by mountains. The map comprises 9 taped-together sheets of laminated loose-leaf paper. Total dimensions: 24" by 36." Medium: colored-pencil. Scale: unknown. I’ve always had in my mind the itchy notion that I ought to do something with Invinciville, the earnest naïve creation that still—embarrassingly, tellingly—must rank as one of my proudest achievements. I just needed the right medium, the right opportunity. Then this issue's TWINS! came along. Did “I”—this same person—really create that artifact? I had to map out this “prose palimpsest” in order to find out.

A complete list of references, in order of appearance:

Annie Dillard, “On Foot in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley,” from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (Harper’s, 1974)

The Anthology of American Folk Music (Folkways 6CD, 1952)

D.W. Meinig, “The Beholding Eye: Ten Versions of the Same Scene,” from The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes (Oxford, 1979)

The Waterboys, This Is the Sea (Island, 1995)

Guy Davenport, “Olson,” from The Geography of the Imagination (Godine, 1981)

Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (FSG, 1978)

Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse,” from The Abundance

Mary Ruefle, “Poetry and the Moon,” from Madness, Rack, and Honey (Wave, 2012);

John Fahey’s quote on the Anthology

John C. Sherman, “In Memoriam: G. Donald Hudson, 1897-1989,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81 (1991)

Royal Trux, Twin Infinitives (Drag City, 1990)

Captain Beefheart, Lick My Decals Off, Baby (Straight, 1970)

Cecil Taylor, It Is in the Brewing Luminous (HatOLOGY, 1980)

Harrison Birtwistle, The Mask of Orpheus (NMC 3CD, 1996)

Anne Orozio’s review of Shadowtime

Brian Ferneyhough, Shadowtime (NMC 2CD, 2012)

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968)

Barbara Ehrenreich, “Welcome to Cancer Land,” Harper’s, November, 2001

Charles E. Rosenberg, “Contested Boundaries: Psychiatry, Disease, and Diagnosis,” from Our Present Complaint: American Medicine, Then and Now (Johns Hopkins, 2007)

Georges Perec, A Void (Gilbert Adair, trans. of La Disparition [1969]; Godine, 1995)

Harry Mathews and Alastair Brotchie, eds., OULIPO Compendium (Make Now, 2005)

Denis Wood, The Power of Maps (Guillford, 1992)

Wikipedia, “Shenandoah Valley” and “Roanoke Valley.”

||

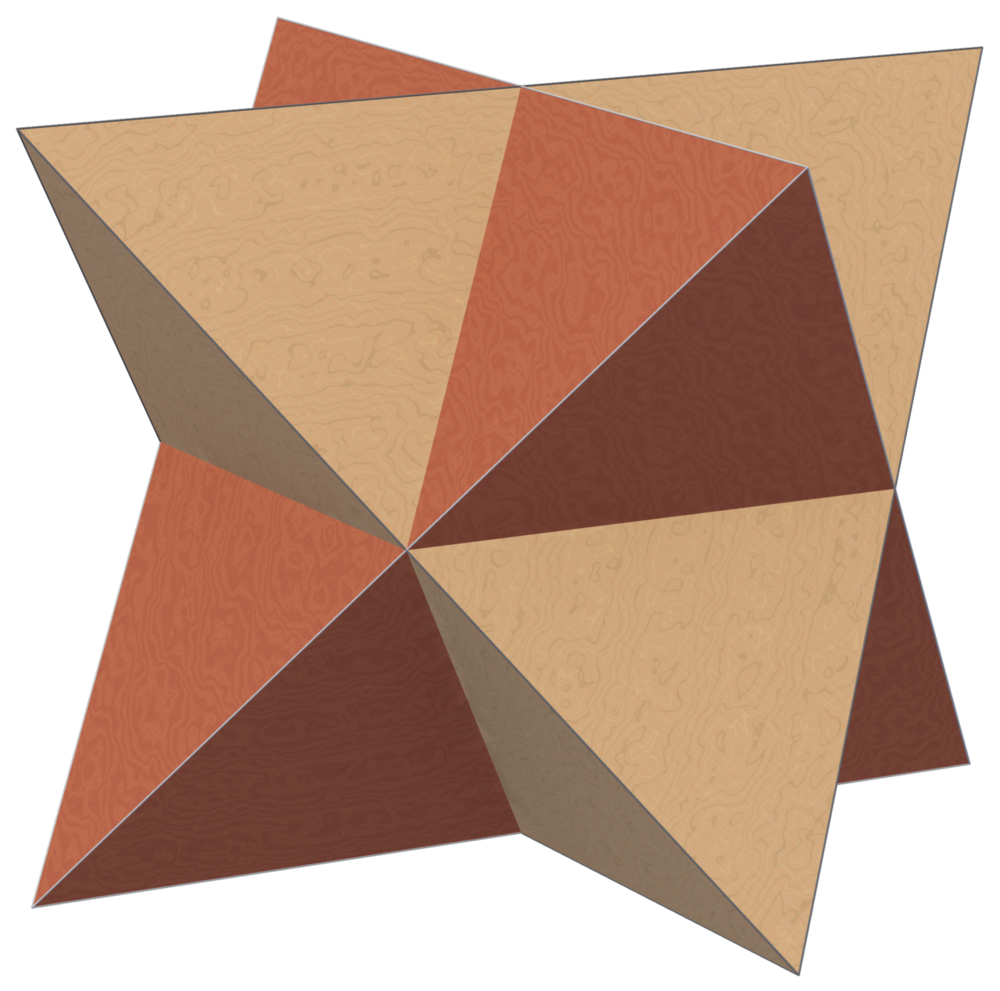

Shira Dentz’s “Come, be one with me” is a lyric representation of a dual compound tetrahedron: twin triangular pyramids interlocking. Imagine a map of a child’s psyche—each pyramid is a reflection/shadow of the other; buried, eclipsed, broken in merged parts. Only by looking at noncontiguous pieces (fragments) and reassembling them in the mind’s eye can wholeness be achieved. The tetrahedron invites this cohesion, and the accompanying textual architecture is part of its language—words, lines, and sections echo, twine, and separate.

Shira Dentz’s “Come, be one with me” is a lyric representation of a dual compound tetrahedron: twin triangular pyramids interlocking. Imagine a map of a child’s psyche—each pyramid is a reflection/shadow of the other; buried, eclipsed, broken in merged parts. Only by looking at noncontiguous pieces (fragments) and reassembling them in the mind’s eye can wholeness be achieved. The tetrahedron invites this cohesion, and the accompanying textual architecture is part of its language—words, lines, and sections echo, twine, and separate.

||

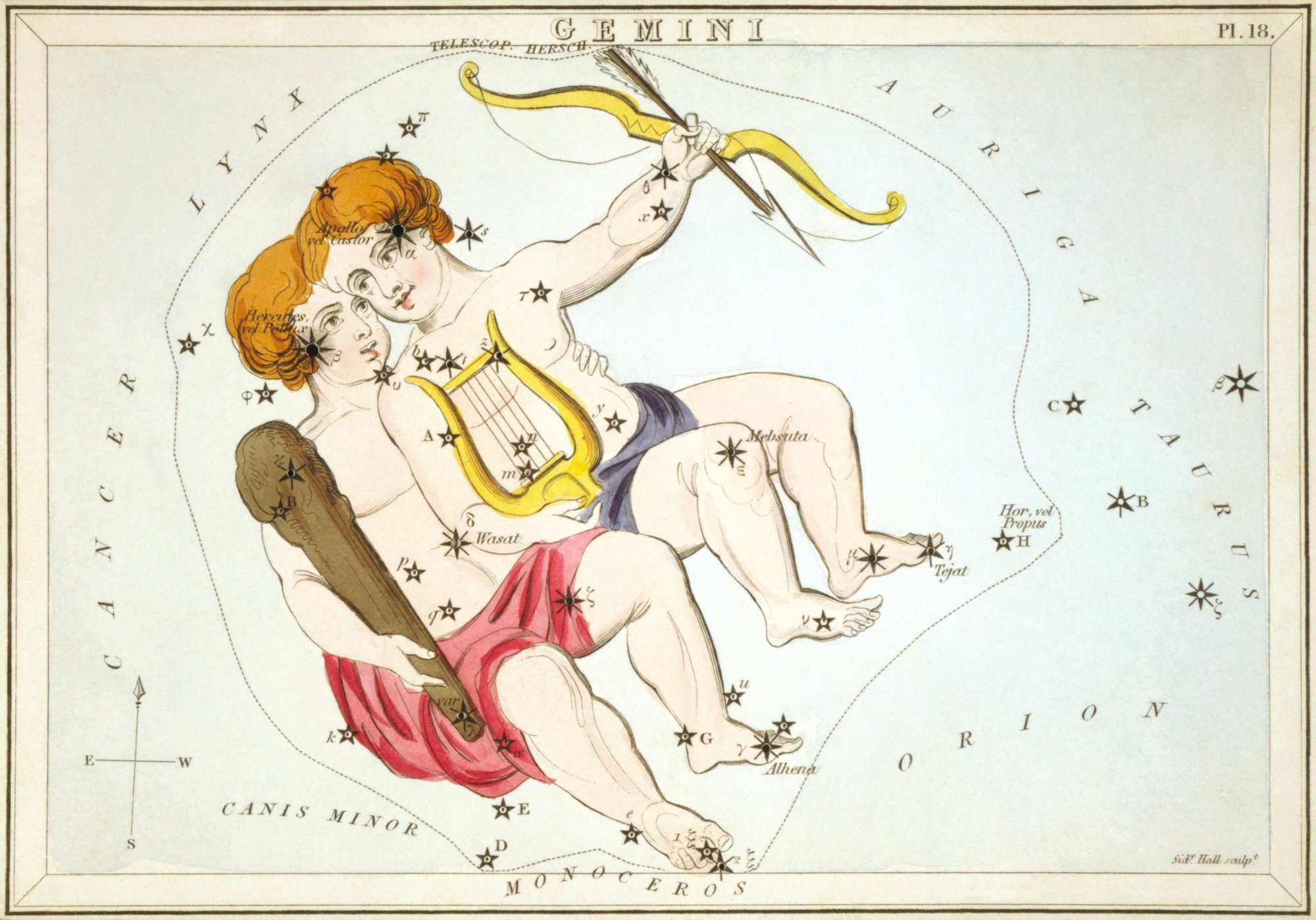

Hannah Hindley & Maddie Norris’ “Castor/Pollux” is twinned with a map of the Gemini constellation, engraved by the British cartographer, Sidney Hall. The image is one of thirty-two cards that Hall engraved, based off illustrations from Alexander Jamieson’s A Celestial Atlas and published in 1824 as Urania’s Mirror. Each of Hall’s cards had holes punched in them to mark the constellation’s stars; if then held to the light, the card would reveal its constellation. The trick was widely praised, although one critic noted that, since candlelight served as the primary form of light at the time of publication, many cards burned.

Hannah Hindley & Maddie Norris’ “Castor/Pollux” is twinned with a map of the Gemini constellation, engraved by the British cartographer, Sidney Hall. The image is one of thirty-two cards that Hall engraved, based off illustrations from Alexander Jamieson’s A Celestial Atlas and published in 1824 as Urania’s Mirror. Each of Hall’s cards had holes punched in them to mark the constellation’s stars; if then held to the light, the card would reveal its constellation. The trick was widely praised, although one critic noted that, since candlelight served as the primary form of light at the time of publication, many cards burned.

||

Jessica Newman’s “Another” is also based off a map of the Castor and Pollux twins, with each line in Newman’s essay corresponding to a different star in the constellation. This map was designed by Johann Bayer and published posthumously in 1655. Bayer was a German lawyer and uronographer, the term for a celestial cartographer, and achieved distinction for compiling an atlas that covered the entire celestial field. Bayer also invented what became known as the Bayer Designation, a new way of identifying stars. In the Bayer designation, each star was catalogued first with a Greek or Latin letter, based on the magnitude of its brightness.

Jessica Newman’s “Another” is also based off a map of the Castor and Pollux twins, with each line in Newman’s essay corresponding to a different star in the constellation. This map was designed by Johann Bayer and published posthumously in 1655. Bayer was a German lawyer and uronographer, the term for a celestial cartographer, and achieved distinction for compiling an atlas that covered the entire celestial field. Bayer also invented what became known as the Bayer Designation, a new way of identifying stars. In the Bayer designation, each star was catalogued first with a Greek or Latin letter, based on the magnitude of its brightness.

||

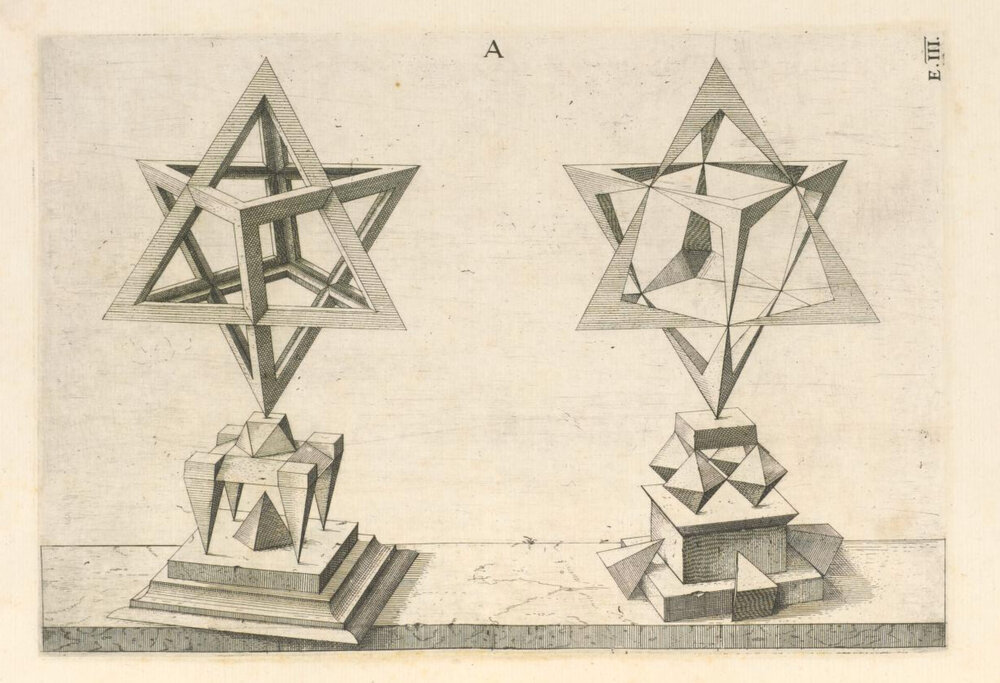

Hilary Plum’s “If you can’t think one without other, you can’t think one” is an ekphrastic twin of Shira Dentz’s piece, both responding to images of dual tetrahedrons. This particular tetrahedron appears in “Perspective of the Regular Bodies,” a “lavish compendium” featuring the work of Jost Amman, a sixteenth century Swiss wood engraver and goldsmith. Amman, his encyclopedia entry states, was “correct and spirited” in his drawing and “minute and accurate” in his drawing. But he “executed too much” to move into the upper echelons of art. A reminder, perhaps, to all of us to take it slow.

Hilary Plum’s “If you can’t think one without other, you can’t think one” is an ekphrastic twin of Shira Dentz’s piece, both responding to images of dual tetrahedrons. This particular tetrahedron appears in “Perspective of the Regular Bodies,” a “lavish compendium” featuring the work of Jost Amman, a sixteenth century Swiss wood engraver and goldsmith. Amman, his encyclopedia entry states, was “correct and spirited” in his drawing and “minute and accurate” in his drawing. But he “executed too much” to move into the upper echelons of art. A reminder, perhaps, to all of us to take it slow.

||

Addie Tsai’s “To Your Own [Dead Ringer] Be True” is paired with a still from the title sequence of the 1988 film Dead Ringers, which features illustrations from Medieval medical treatises on childbirth and twins. While Tsai’s essay contains all the information you need to know about the film and more, one might add that one of this film’s original working titles was “Twins,” until director David Cronenberg was informed of a potential copyright issue with the Danny Devito-Arnold Schwarzenegger classic scheduled for the same year and the name was changed.

Addie Tsai’s “To Your Own [Dead Ringer] Be True” is paired with a still from the title sequence of the 1988 film Dead Ringers, which features illustrations from Medieval medical treatises on childbirth and twins. While Tsai’s essay contains all the information you need to know about the film and more, one might add that one of this film’s original working titles was “Twins,” until director David Cronenberg was informed of a potential copyright issue with the Danny Devito-Arnold Schwarzenegger classic scheduled for the same year and the name was changed.

||

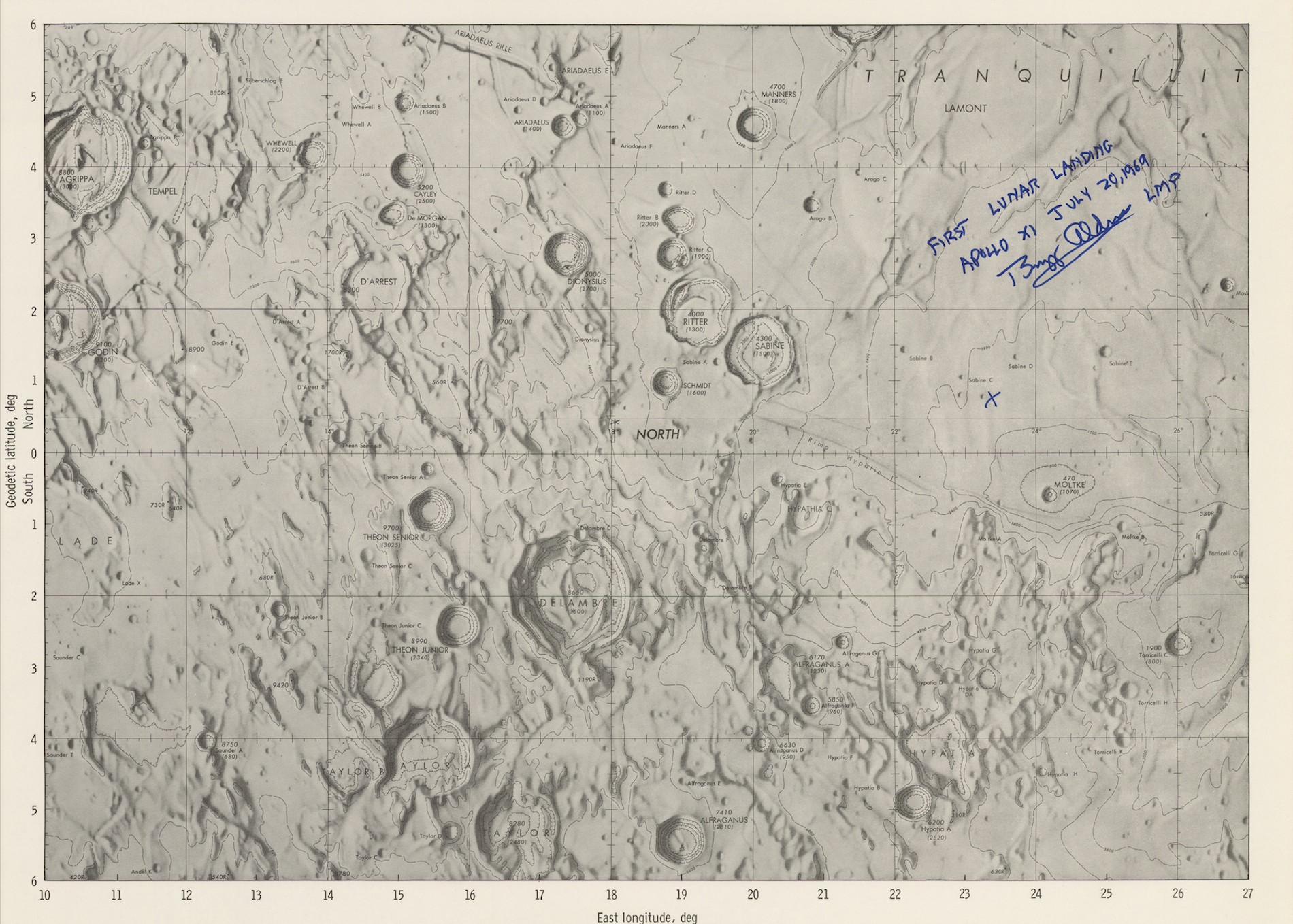

Cori Winrock’s “Variants on the Moon” contains, at its outset, a map depicting Apollo XI’s lunar landing on July 20, 1969. The map depicts the section in which Apollo XI landed and is signed by Buzz Aldrin. In 2002, the 72-year-old Aldrin gained further fame for punching the conspiracy theorist Bart Sibrel in the jaw, after Sibrel cornered Aldrin and attempted to have him swear on a Bible that the lunar landing was not faked. A dedicated numerologist might point to the doubling between Apollo’s eleventh mission and this our eleventh issue. A dedicated conspiracy theorist might point out that Aldrin never did swear on that Bible.

Cori Winrock’s “Variants on the Moon” contains, at its outset, a map depicting Apollo XI’s lunar landing on July 20, 1969. The map depicts the section in which Apollo XI landed and is signed by Buzz Aldrin. In 2002, the 72-year-old Aldrin gained further fame for punching the conspiracy theorist Bart Sibrel in the jaw, after Sibrel cornered Aldrin and attempted to have him swear on a Bible that the lunar landing was not faked. A dedicated numerologist might point to the doubling between Apollo’s eleventh mission and this our eleventh issue. A dedicated conspiracy theorist might point out that Aldrin never did swear on that Bible.

Attribution for quotations (contained within plus signs) and other source materials:

E.B. White, The New Yorker, “Notes and Comments” July 18, 1969

Gertrude Stein, The World is Round

T. Adler Books, The Moon, 1968-1972

Emily Dickinson Archive (FAQ)

Alice Fulton, “Maidenhead,” stanzas 1,4,8

Margaret Wise Brown, Goodnight Moon

Douglas Lantry, Journal of Design History, “Dress for Egress: Smithsonian Apollo Spacesuit Collection,” 2001

Nicholas de Monchaux, Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo

Apollo seamstresses, Moonwalk One, The Director’s Cut

David Kestenbaum, NPR: The Magic Show, Act Two: “The Lady Vanishes,” June 30, 2017

Daneen Waldrop, Emily Dickinson and the Labor of Clothing

Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons

University of Rochester Golisano Children’s Hospital, Visiting the NICU

Liz Stinson, Wired online, “X-Rays Reveal the Insane Innards of Space Suits”

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Jorie Graham, “To a Friend Going Blind”

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.