—for J

What would you say, dear Reader, if I admit to you that even I do not know which one I am?

Which is a somewhat innocuous word, I suppose, but for me, it’s a word I can only associate with a sentence in which the word is bookended, one on each side, a beginning which is also an end.

Which one is which?

A woman I knew once, who knew me until she didn’t (a sentence I often utter), giggled the first and only time I introduced her to my twin, clapping her hands together as if we were a magic trick: Oh, my two little bookends! She cooed as we spoke, our voices unrecognizable from one another, a truth even I cannot deny.

Every time I hear myself played back, all I hear is her.

This is the part of the story where I offer you a confession.

I have never made this confession before, by which I mean to say that when pressed, I have withheld the truth, redirected the conversation, or lied outright.

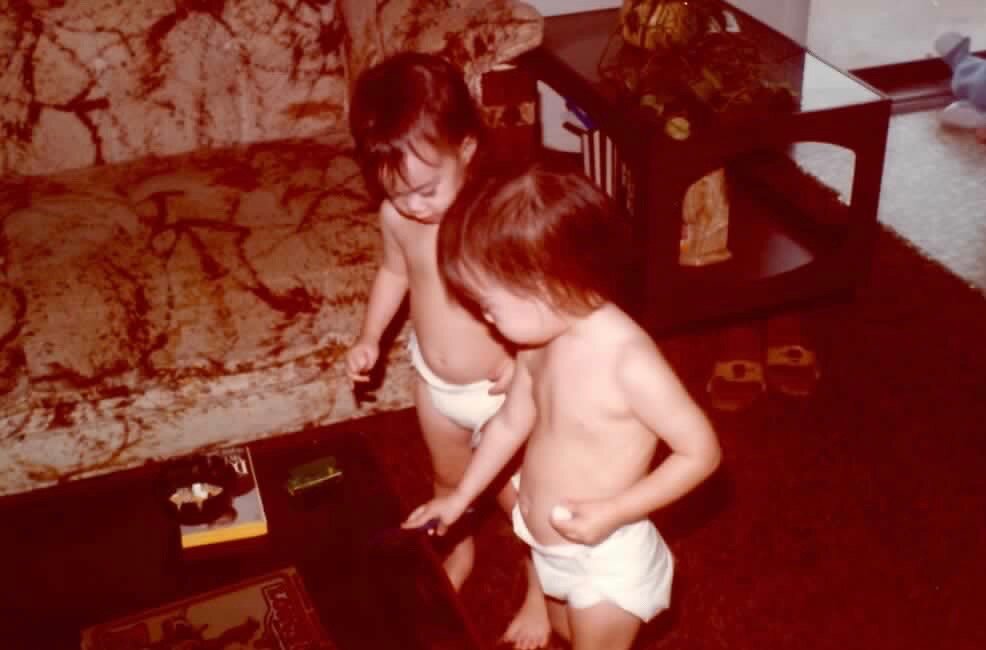

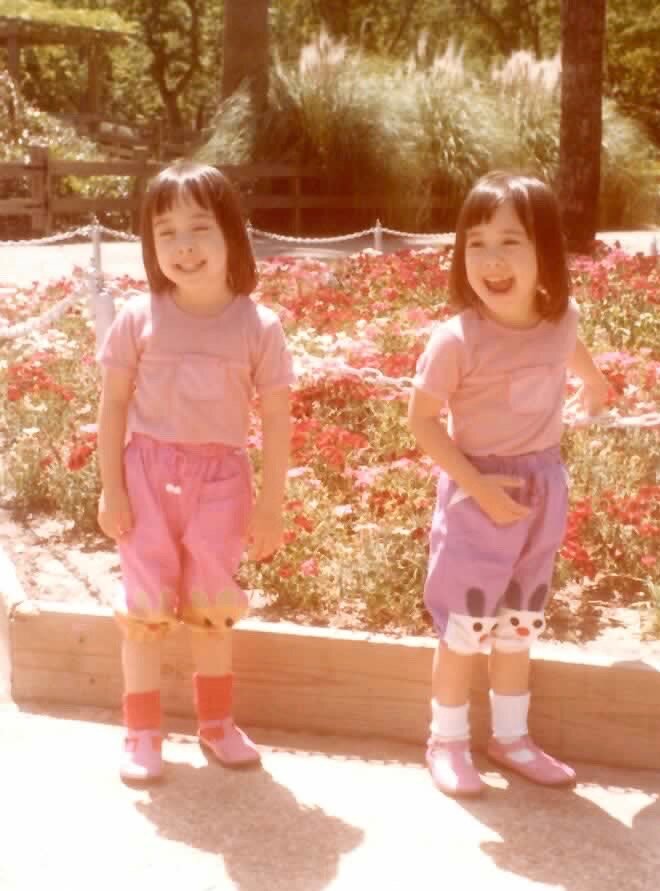

A you and a me sit on a sofa or flop our bellies on a bed with an old photo album or a shoebox of drugstore prints between us. We fall into the doubles of doubles of doubles—our two faces alongside, in front of, behind, diagonal, and so on. When I say doubles, when I say our two faces, I mean to say her face and my face, our doubled diapers, her grin paired with my scowl, and so on. And vice versa.

A photo sandwiched here and there will hold just a single face, but it is a rare occurrence, a posed strip of the same image a result of force, the requisite yearly Picture Day.

The you in this story wants to be the one to get it right, the one to know without hesitation which one is the me whose bellied skin face down on the mattress grazes your own.

The me in this story wants to convince the you I have no doubt which face to prick with my finger in recognition of my own.

Perhaps the reason I am finally ready to confess is because of the filmmaker Jonathan Caouette, a new you in the story, a new sofa, a new belly, a person I’ve encountered who opens up what a twin can be, both single and joined, separate and united.

This second person has never thought to ask which one is which.

It has never occurred to me there could be a you in this recurring scenario for whom that question was unnecessary.

It has never occurred to me I could feel safe to admit I don’t always know where she ended and I began.

I’d learned tricks over the years for how to tell it straight: my twin’s eyes a little farther apart than mine. Her freckle above the lip on its mirroring side. But the biggest trick, one even my twin admitted to using, is how often I am the one wearing the goofy grin, playing to the camera’s eye as if it were a mother or a father or a twin I could be safe with. The openness of the grins strike me. They have a sense of freedom I never embodied when there wasn’t a lens standing between me and whoever it was holding the camera.

But, not always.

Sometimes all I had to rely on was the color of the identical outfits we wore—sometimes it is only the memory of which color I was given to wear that determines one body versus another, this face versus that one.

But sometimes my memory escapes me. Sometimes the she in the photo feels like me. Sometimes the me in the photo feels like she.

And, so, here is my confession: Sometimes, dear Reader, dear Holder of the Photo between us, I become whoever it is you think I am.

Which is another way of saying I always already feel as though I were a haunting, an apparition, a doubling and a disappearing all at once.

dead ringer (n.)

a person or a thing that seems exactly like someone or something else.

dead-center (adj., adv.)

“in the exact middle,” 1874, the noun phrase (1836) in reference to lathes or other rotating machinery, meaning the point which does not revolve; see dead (adj.).

dead (adj.)

Middle English, ded, from Old English dead “having ceased to live,” also “torpid, dull;” of water, “still, standing.”

Meaning “insensible, void of perception” is from early 13c. Of places, “inactive, dull,” from 1580s. Of sound, “muffled,” 1520s. Used from 16c as “utter, absolute, quite” (as in dead drunk, 1590s); from 1590s as “quite, certain, sure, unerring;” by 1881 as “direct, straight.”

Dead on is from 1889, from marksmanship. Dead duck “person defeated or soon to be, useless person,” is by 1844, originally in U.S. politics.

ringer (n.)

early 15c., “one who rings” (a bell), agent noun from ring (v. 1). In quotes (and by extension, horseshoes) from 1863, from ring (v. 2). Especially in be a dead ringer for “resemble closely,” 1891, from ringer, a fast horse entered fraudulently in a race in place of a slow one (the verb to ring in this sense is attested from 1812), possibly from British ring in “substitute, exchange,” via ring the changes, “substitute counterfeit money for good,” a pun on ring the changes in the sense of play the regular series of variations in a peal of bells (1610s).

ringer (n.)

a ringer is a contestant who lies about his experience.

||

Dead Ringers: a 1988 Canadian-American psychological body horror film starring Jeremy Irons in a dual role as identical twin gynecologists. The film is loosely based on the lives of real-life twin doctors Stewart and Cyril Marcus, who died together under mysterious circumstances in 1975. The twins were found dead in their apartment on the Upper East Side, most likely by cause of barbiturate addiction. Cyril was found lying face down on a bed, wearing only undershorts. His brother was found lying face up on the floor, nude.

Initially, Irons had two separate dressing rooms and two separate wardrobes which he would use depending on which character he was playing at the time. Soon he realized that “the whole point of the story is you should sometimes be confused as to which is which,” after which he moved to a single dressing room and mixed the wardrobes together, and found an “internal way” to play each character differently, using the Alexander technique to give them “different energy points,” which gave them slightly different appearances. During filming, Irons kept track of whether he was playing Elliott or Beverly by always playing one with his weight on the balls of his feet and the other with his weight on his heels.

Initially, Irons had two separate dressing rooms and two separate wardrobes which he would use depending on which character he was playing at the time. Soon he realized that “the whole point of the story is you should sometimes be confused as to which is which,” after which he moved to a single dressing room and mixed the wardrobes together, and found an “internal way” to play each character differently, using the Alexander technique to give them “different energy points,” which gave them slightly different appearances. During filming, Irons kept track of whether he was playing Elliott or Beverly by always playing one with his weight on the balls of his feet and the other with his weight on his heels.

The Bionic Woman, “Deadly Ringer”: Jaime Sommers is knocked out while doing some needlework at home and wakes up in a cell at a state penitentiary, having switched places with her double, Lisa Galloway. Meanwhile, Lisa has begun to impersonate Jaime at her place of work, teaching at Ventura Air Force base. Lisa and her benefactor Dr. Courtney mistakenly think Jaime’s super strength is derived from a substance invented by Rudy Wells called adrenalizine and Lisa has been charged with stealing more of it. In prison, Jaime is about to be forced to undergo plastic surgery against her will to restore Galloway’s old face. Lisa is enjoying Jaime’s life so much she doesn’t want to leave it behind after she steals the adrenalizine. Lisa keeps some for herself to have access to Jaime’s super strength. Jaime has escaped from prison but finds nobody believes her when she tells them who she is.

||

Dear Reader,

The story I am about to tell you I have told before.

It’s a story I must continue to tell until the need to tell it has left me, until the reason I continue to utter it becomes clear to me.

The story, it continues to change, revolve, elongate, and quicken, depending on which teller I am at the time, which listener.

The story, it is a shape shifting in the grass, a shadow lingering in a murky pond.

This story includes Jonathan, the new you, but I imagine that this twin can feel this way to me, precisely (read: deadly) because he is not my twin (read: ringer), my double, my lookalike, my mirror. Or, perhaps, it makes more sense to say that because our mirroring is only clear between the two of us, a reflection that arises out of our insides rather than the resemblance of our outsides, the doubling is no longer a trauma, but an insight and a joy, a connection and a relief.

The first time I felt a kind of synchronicity, a twinning, a seeing, was almost fifteen years ago, but it would not happen in person. It would happen when I witnessed what he made, Tarnation, a film with many mirrors and many doubles and many selves. The film would depict a world very different from the one I had lived in up to that point, but somewhere inside of me I had an intuition that if I shared with him what I made, or the stories that made up the totality of me, particularly the me whose skin tingled with reckoning and recognition when I consumed that thing he made, that he would see me, and he would understand.

At the same time, quite coincidentally, I happened to watch Dead Ringers for the first time, the only film about identical twins in which I could see something of my own experience.

Almost fifteen years later, he would encourage me to consume another fictional artifact, one I would interpret very differently from many who had consumed it before, a two-part episode from The Bionic Woman, one which didn’t even depict twins, but two women made to be doubles, also played by one actor.

It leads me to wonder, will there ever come a time where we’ll watch a film of twins in which twins actually play themselves? In which even the film itself isn’t, in its own way, revealing what it means for one person to pose as two?

||

I haven’t gotten to the story yet.

Forgive me, dear Reader, if I take my time. Let me try again.

Perhaps the easiest way to tell something is to tell it through.

One day, I was lying on my belly on a mattress on the top floor of a duplex.

It was days before I would travel to New York City in order to witness another work of art by Jonathan, days before I would plant some seeds in that city in an attempt to possibly move there.

Although I had been writing for almost fifteen years by then, I still didn’t have a website.

I thought, on this day, as the heat sweltered outside my window, and the bottom of my shirt folded itself into a ball where it rose just above my belly like the newly-pressed flowers my mother used to sandwich in between the pages of her old copy of Webster’s Dictionary, that perhaps I should look into building a website if I wanted to figure out a way to build a life for myself in New York.

It was an innocuous thought, a passing moment that fluttered in my mind long enough that I took a break from checking my email to see what I needed to do to register my domain name.

One moment, my body, a neutral container of glorious ennui.

The next, my body a frenzied spin.

I searched my first and last name.

Then my first, middle, and last.

Both were already taken by someone else. Not just any someone.

Finally, once I knew that what caused my skin to quiver was linked to my mirror twin who had sought to undo me, I searched for the working title of the memoir under contract at the time.

I hit enter.

After I learned that my twin stole three of my domain names, I longed for the carefree and casual way in which I’d tapped my pinky finger the first time. I would never feel that sense of freedom again.

It sounds like a bad movie, but that doesn’t make it fictitious.

||

My twin racing to get to the phone when my college boyfriend rings me at home, so that she can flirt with him a few minutes before I realize he’s called.

My twin discovering my crushes (at least the boy ones) so that she can seduce them, and then reject them as soon as they reciprocate their interest.

My twin tickling that same college boyfriend’s supposed six pack while her boyfriend and I talk behind them, on our way to dinner.

My twin sister stole three domain names that either held my given name or the name of something I had created. She will never admit the real reason why.

What did it mean for her to steal my name? What did it mean for her to touch everything I hoped would only be mine? How could I believe that anyone would choose me over her if our faces made them question whether the you they thought they wanted was another you, instead?

||

My hands started to shake. My tears spilled over the balloons of my red and puffy eyes.

I dialed the number of the first woman I ever loved, the woman whom I hoped would immediately rescue me from the feeling of being emptied out by the only person in the world who shares my face.

But, she had to tend to the person that was the priority in her life. I was used to being second.

She did, however, offer me something in her absence. She told me to do what I had always done in the face of danger, pain, grief, and joy: Make something.

I leaned my SLR against a stack of books facing a full-length mirror against the wall. I made up my face. I smeared it. I sang. I stared at the mirror until I could see through it, until I could barely see at all. I tried to make sense of who I could be with this two-face, how I could insist on my own existence no matter how much my twin tried to bank on the currency of my face (read: ring in). I’d spent the past twenty years as a writer and as an artist, and suddenly she was attempting to fuse with me to such an extent that the line between she and I would blur like the ocean when it washes away a toe-carved line in the sand.

I would speak to a lawyer. I would weep for the self I was before this moment, the one who believed in a selfhood that would remain untouched by her twin. I would weep for the self that believed that those who loved you or read your work or knew what you had suffered being a twin brought up in a traumatic and unstable childhood would get it enough not to accept her friend request or fall for her need to be seen, even if it was through me that she would ask for that sight. I would weep for the I who could no longer trust the body that was made of the same blood as her own, that swam in the same pre-verbal and pre-birth fluid. That body felt like water, a water I could no longer see as safe. No matter the dopamine rush, no matter the primal connection, no matter the love I felt unlike any other I would ever feel or conceive of, I would have to trick myself into distrusting it. Even when I didn’t. Especially when I didn’t.

||

It seems right that the first time I would come upon Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation, a piece of art that would make me feel seen in a way nothing has before or since would not only be linked to the same summer I would watch Dead Ringers, but also that I would come to discover that my twin’s stealing my domain names happened just days before I would make his acquaintance, even if briefly, even if seemingly ephemeral at the time.

One twin impersonates another so that he can make love to his lover.

Eliot: Bev, you haven’t done anything until I’ve done it, too. You haven’t fucked Claire Niveau until you’ve told me about it.

Bev: Then I haven’t fucked Claire Niveau!

||

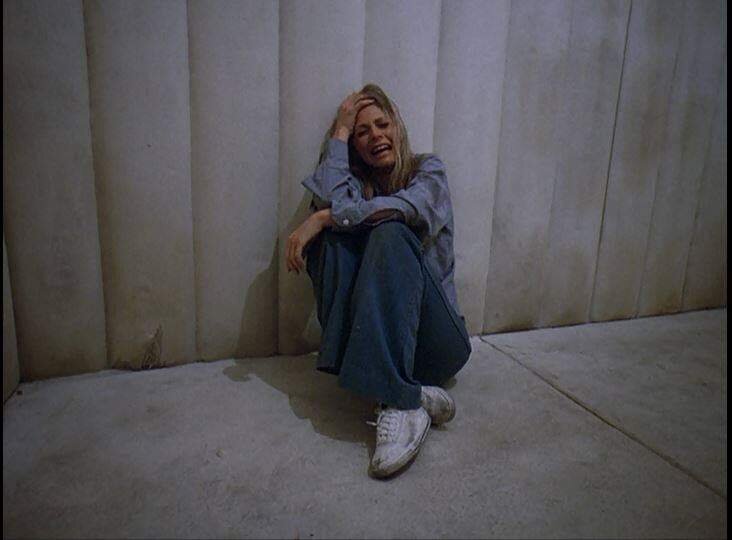

It feels silly, but I’ll admit it: When I read the words on the embroidery Jaime stitches before she’s gassed and replaced with Lisa in the state penitentiary—To Your Own Self Be True—my eyes tear up. It’s a not altogether different tear that escapes when I remember clicking on the link that enables a person to find out who’s registered the domain name you want, and I see her name, clear as the faces we share in our family snapshots.

Is this what my twin looks like, I wonder, when I watch Lisa and her self-satisfied grin as she wears her double’s clothes, stops answering to her own name, and poses for a photo with her double’s parents?

Is this what she looks like when she writes work derivative of work I’ve not only written but, in some instances, pulled to protect her feelings?

Is this what she looks like when she uses my currency (her word, not mine) in order to get closer to the community I’ve been building since I was 18, a community she used to tease me for caring about?

Is this what she looks like when she tells people she imagines I might know that I’m crazy, a pathological liar, and not to be trusted?

The impression of glee that falls across Lisa’s face and carves itself into the glassy screen of my laptop is one my mind peels off of her skin and affixes to my twin’s.

But, it is not an impression of glee I recognize in myself.

It is hysteria. It is the white padded room. It is Jaime lying on the ground, hearing the word Lisa echo over and over in her ears. It is the wall covered with prints of Lisa’s face. It is Jaime crying and moaning as she rips them off the wall. It is the lack of clarity behind whether or not the prints are actually on the wall or in her imagination.

It is hysteria. It is the white padded room. It is Jaime lying on the ground, hearing the word Lisa echo over and over in her ears. It is the wall covered with prints of Lisa’s face. It is Jaime crying and moaning as she rips them off the wall. It is the lack of clarity behind whether or not the prints are actually on the wall or in her imagination.

What if, in all this time, the me I always imagined I was in the photos with the goofy grin, was you?

What if, in all this time, the you I always imagined in the photos with the forlorn face blinking herself out of the frame, was me, afraid that the more real I became, the more you could take it from me?

What if, in all this time, the me I always imagined to be writing is, in fact, you?

||

If you can manifest your own family, is it possible to manifest your own twin?

Joined, but separate, fused, but wholly individual?

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Addie Tsai holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College and a PhD in Dance from Texas Woman's University. Her queer Asian Young Adult novel, Dear Twin, is forthcoming from Metonymy Press in November 2019. She is Nonfiction Editor at The Grief Diaries, Senior Associate Editor at The Flexible Persona, Associate Fiction Editor at Anomaly, and Senior Editor of Culture and Interviews at Raising Mothers.

8117 Pelican Harbour Dr

Lake Worth, FL 33467

What may have seemed a simple house in a gated community to some was like a palace to me. It was the house I was invited to on a whim with a man and a five-year-old child whose love and comfort I craved. I found, instead, the kinship and love of that man’s queer sister, a woman who often felt like a mother to me, just as I was discovering my own queerness, my own capacity to love bodies I’d resisted acknowledging within myself for a decade. I will never forget the post-beach custards we would get almost daily at the local outdoor stand barefoot and wet after snorkeling near the shore and hunting for seashells, the rows and rows of palm trees, or the hours we spent in the covered pool out back, watching that glorious five-year-old learn swan dives and the butterfly with a fearlessness I would never know as a child, or even now.