Legend

Journeys

In “I Have No Choice But To Keep Looking,” which follows the survivors of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami as they search for the lost bodies of their loved ones, Jen Percy details the many possible journeys a corpse can take once it’s lost at sea. The body could sink downwards where it enters the water, staying in place, or it could travel, caught in a current or tide. If the body finds itself tangled up in fishing trawl, it might end up in Hawai’i. Percy writes of half-eaten corpses, of scuba divers found belly-up like insects, of how the right set of clothes could preserve a body’s bones in its human shape long after the flesh has decomposed. In short, no one really knows what will happen to a body lost at sea, or what form it will take. Its fate depends upon a number of factors, not least of which are chance and luck, just as the body’s relegation to the sea in the first place depends upon such factors. The journey can’t be mapped until afterwards, if it can be mapped at all. By then, it proves of little use to the body, but of utmost importance to whoever remains to read it.

For our ninth issue, we asked contributors to map journeys. What we found was not so much a map of a theme—some legend or key as to what constitutes a journey; a definition that reached the definitive—as much as the summons for immersion, for diving deep. Who knew it wasn’t the destination, but the journey? In this issue, you will find road trips and marathons, wayfarers and weigh stations, distances traveled that seem impossible and others that seem deceptively easy. There are journeys within journeys, such as E.M. Tran’s “Soft Earth” in which a recent Vietnamese refugee travels across late-night D.C., searching in vain for the man supposed to drive him home. Journeys motivated by a need for escape, by love or lust or whimsy or all of the above, as in Katya Apekina’s “Lewis and Clark” and Jenny Xie’s “Tessa Comes to Be Alone.” There are anti-journeys, characters stuck in their respective limbos, such as a castle on the edge of Switzerland in Terese Svoboda’s “Five Beards Not Counting the Goats’” or a women’s shelter in Shamala Gallagher’s “Safe House.”

Alongside these are the texts that disassemble journeys, pieces whose oblique, discursive, abstract, and durational forms draw attention to ways in which journeys are constructed. Berry Grass’s “902 Sunset Strip” embeds a personal narrative of identity and intimacy within the rigidity of an architectural survey form, pushing against and ultimately expanding the little, bureaucratic rectangles that stand to constrain it. Marco Wilkinson’s “A Gardener’s Education (Plant Body)” is an ivy-covered wall of paragraphs and lines that, like the plant life that inspires the form, want to follow clear vectors towards sources of light—autobiographical lucidity—but end up tangling with and creeping away from one another, creating a reading experience as forked and circuitous as Wilkinson’s personal narrative. These pieces demonstrate the variability and improbability of a journey by drawing attention to the reader’s own complicated journey through text, image, and other modalities.

Given the metatextuality of these pieces, it’s hard not to use the theme of this issue, our ninth now, as an opportunity and lens to inspect the ongoingness of publishing a periodical. The homophonic ring of the two words “journey” and “journal” is no coincidence; both are rooted in a daily labor. Despite this, the more quotidian details necessary to arrive at your destination are often excised to make the journey seem more dramatic or epic. Truth be told, a journey can be a slog, in our case months of planning and logistics that make editing and publishing such exciting work possible. This is why it’s fitting that this issue is the first to feature the work of our contributing editors, Andrew Sargus Klein and Nic Leigh. Not only have they brought energy and acumen that have both expanded and honed the journal’s mission, but they’ve worked assiduously through the less glamorous duties that come with the position. They’ve made the daily labor of the journal less laborious in all senses, and for that we thank them.

We hope you enjoy the journey.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Katya Apekina’s “Lewis and Clark” is a modern-day road trip, in which the narrator and her companion head west while consulting Lewis and Clark: An Adventure for the Ages and bickering over who is Lewis and who Clark. The story responds to “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track, Across the Western Portion of North America.” Lewis copied the map from one of Clark’s original drawings before it was engraved by a man named Samuel Harrison. The map is known for being the first accurate depiction of the sources of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. The map was published in 1814, five years after Meriwether Lewis committed suicide. “We’re both Lewis,” one of Apekina’s characters tells another. —TMyL

Katya Apekina’s “Lewis and Clark” is a modern-day road trip, in which the narrator and her companion head west while consulting Lewis and Clark: An Adventure for the Ages and bickering over who is Lewis and who Clark. The story responds to “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track, Across the Western Portion of North America.” Lewis copied the map from one of Clark’s original drawings before it was engraved by a man named Samuel Harrison. The map is known for being the first accurate depiction of the sources of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. The map was published in 1814, five years after Meriwether Lewis committed suicide. “We’re both Lewis,” one of Apekina’s characters tells another. —TMyL

Caroline Crew’s “Union” responds to a “Map of the Submarine Telegraph Between America & Europe,” a visualization of the first transatlantic telegraph, as designed by Cyrus West Field. The telegraph ran along a submarine plateau between Newfoundland and Ireland. The map, alongside a record of Field’s achievement, appears in Henry Howe’s “Adventures and achievements of Americans: a series of narratives illustrating their heroism, self-reliance, genius and enterprise.” Consider Crew’s essay a necessary chaser to that title. —TMyL

Shamala Gallagher’s “Safe House” is an essay about journeys to and from a shelter from domestic violence, “a house I can’t really tell you about.” Because the house’s location must remain anonymous, the essay is paired with an anti-map, in this case a drawing from the author.

Shamala Gallagher’s “Safe House” is an essay about journeys to and from a shelter from domestic violence, “a house I can’t really tell you about.” Because the house’s location must remain anonymous, the essay is paired with an anti-map, in this case a drawing from the author.

Gallagher gave the following statement about the drawing: “Recently I found this ‘map’ in a stack of old papers. I have a box in which I mean to organize my important papers, but mostly I throw them into the box, ignoring the dividers, and shut it. This drawing was in there, and I don’t remember when I drew it, but because it’s intentionally stained with wine, I probably made it in San Francisco, copying my then-roommate Alida Payson, an artist, whose teacher asked her: Why are you painting with non-perishable paints? Your work is all about decay. That was ten years ago—or maybe I made it in the first house I lived in in Athens, Georgia—but in homage, then, to Alida. The only thing that is clear is that I made it before I quit drinking, and during a time when I was wary of home, of family, and I thought my only allegiance was to wildness. I don’t feel any less wild now, but I’m sober, and my baby, in the other room, is waking, so I have to go.” —TMyL

Colby Gillette’s “Chez Pas: Backcountry Cairn” is a map of the many aspects—“landscape, fauna, conversation, dreams, weather, meals, mistakes, etc.”—of une grande randonnée Gillette took through La Creuse, a department in Central France. La Creuse lies along what has been termed the empty diagonal, a band of depopulated departments spanning the entire country from its northeast border to Belgium to its southwest one with Spain. This wasn’t always so; populations along this axis have been shrinking since the industrial revolution, which began an extended and ongoing rural emigration that has shrunk the number of Creusois from its height of 287,075 in 1851 to a number that today hovers below 120,000. In Victor Levasseur’s national atlas of 1852, La Creuse is presented as a thriving agriculture region known for its livestock and game, Aubusson rugs, and, unwittingly, leeches collected from the marshes outside La Souterraine that would be sent to Paris for medical use. Today, even leech populations are scarce in the region. The reason, again, is industrialization: a mix of pesticides and the draining of these wetlands. —NG

Colby Gillette’s “Chez Pas: Backcountry Cairn” is a map of the many aspects—“landscape, fauna, conversation, dreams, weather, meals, mistakes, etc.”—of une grande randonnée Gillette took through La Creuse, a department in Central France. La Creuse lies along what has been termed the empty diagonal, a band of depopulated departments spanning the entire country from its northeast border to Belgium to its southwest one with Spain. This wasn’t always so; populations along this axis have been shrinking since the industrial revolution, which began an extended and ongoing rural emigration that has shrunk the number of Creusois from its height of 287,075 in 1851 to a number that today hovers below 120,000. In Victor Levasseur’s national atlas of 1852, La Creuse is presented as a thriving agriculture region known for its livestock and game, Aubusson rugs, and, unwittingly, leeches collected from the marshes outside La Souterraine that would be sent to Paris for medical use. Today, even leech populations are scarce in the region. The reason, again, is industrialization: a mix of pesticides and the draining of these wetlands. —NG

Berry Grass’ “Architectural Survey Form: 902 Sunset Strip” entrusts memoir with bureaucracy by mapping the interior progression of the property in question: 902 Sunset Strip. Its historic use is “horror and refuge” — “Desire disturbs the air in the house, thickens the place like roux, and dad would swat and swat as if clearing smoke.”

Berry Grass’ “Architectural Survey Form: 902 Sunset Strip” entrusts memoir with bureaucracy by mapping the interior progression of the property in question: 902 Sunset Strip. Its historic use is “horror and refuge” — “Desire disturbs the air in the house, thickens the place like roux, and dad would swat and swat as if clearing smoke.”

Its current owners are unknown. This is a paper trail, an accounting, an archive of a mother’s interior decoration. There’s more work to be done. —ASK

Devin Gael Kelly’s “The Map of Love Is Just a Returning” maps a 24-hour race near Brooklet, Georgia. His father, prodigious runner no longer, begins the recovery process after hip replacement surgery. The body is a fragile and impossible thing.

Kelly considers the variables of love; determines the moment of pain in which he becomes the roots and the rabbits running through them; and is unafraid: “Because there is pain in love, I believe we can become love, too.” —ASK

Gabriel Palacios’ “From The Spanish Trail Motel” responds to a map entitled Provincia de la nueva Andaluzia de San Juan Baptista de Sonora. In an article entitled “Who Named Arizona?”, Donald T. Garate notes the map’s intricacy, how it’s “marked by carefully drawn symbols” and is “painstakingly drawn to a clearly delineated scale.” “The elaborate symbol showing the four cardinal directions and the frame drawn around the map’s title,” Garate writes, “must have taken an extensive amount of time with quill pen and ink.” The map is also, as Palacios notes, “almost certainly falsified.” Its cartographer, Gabriel Prudhom Butron y Mujica, also happens to be Palacios’ 8th great-grandfather. “These misdirections,” Palacios writes, “these fundamental wrongnesses of my colonial ancestral inheritance, are at the heart of these poems.” —TMyL

Gabriel Palacios’ “From The Spanish Trail Motel” responds to a map entitled Provincia de la nueva Andaluzia de San Juan Baptista de Sonora. In an article entitled “Who Named Arizona?”, Donald T. Garate notes the map’s intricacy, how it’s “marked by carefully drawn symbols” and is “painstakingly drawn to a clearly delineated scale.” “The elaborate symbol showing the four cardinal directions and the frame drawn around the map’s title,” Garate writes, “must have taken an extensive amount of time with quill pen and ink.” The map is also, as Palacios notes, “almost certainly falsified.” Its cartographer, Gabriel Prudhom Butron y Mujica, also happens to be Palacios’ 8th great-grandfather. “These misdirections,” Palacios writes, “these fundamental wrongnesses of my colonial ancestral inheritance, are at the heart of these poems.” —TMyL

Russell Persson’s “These Threads Who Lead to Bramble” maps the author’s own travels made a quarter of a century ago in an attempt to access memory, only to find no distinction there between the accurate and the imprecise. Persson’s sketchy and colorless maps are nondescript, like recall itself; the piece is a shrub of what’s left, an act of self-preservation. —NL

Russell Persson’s “These Threads Who Lead to Bramble” maps the author’s own travels made a quarter of a century ago in an attempt to access memory, only to find no distinction there between the accurate and the imprecise. Persson’s sketchy and colorless maps are nondescript, like recall itself; the piece is a shrub of what’s left, an act of self-preservation. —NL

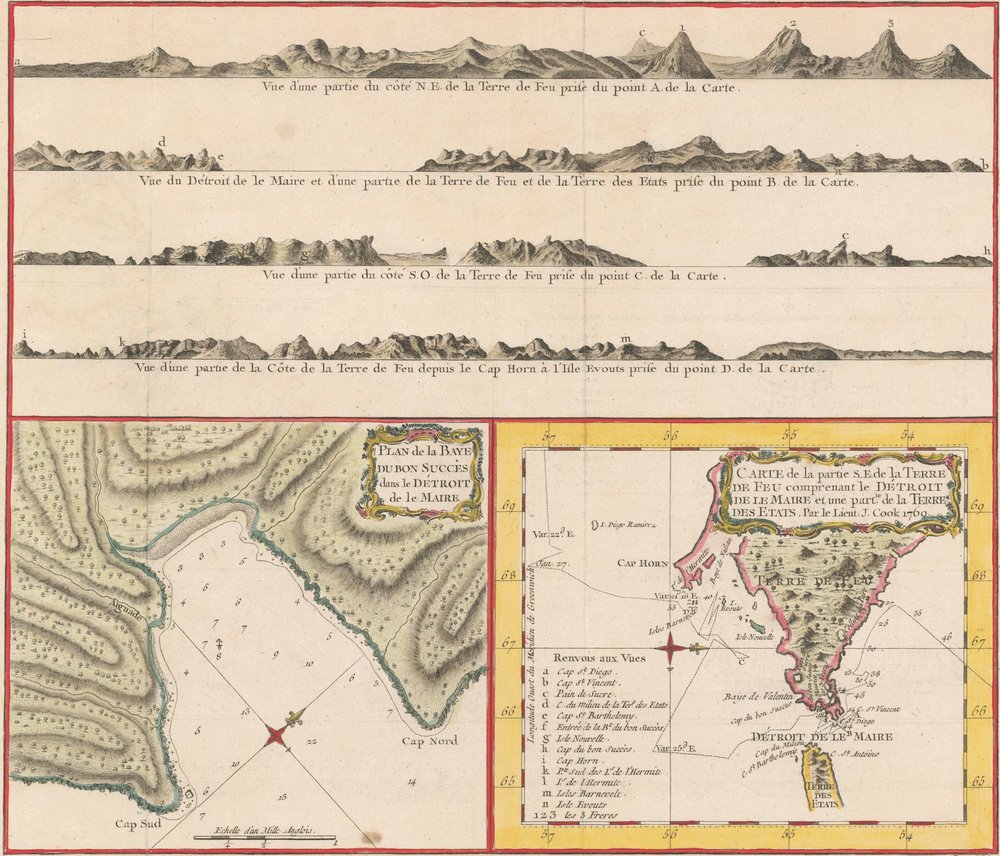

Ed Steck’s “I Take the Glowing Path” maps his own swamp wanderings onto copperplate maps drawn by eighteenth-century cartographer Rigobert Bonne that depict Lieutenant James Cook’s passage by Cape Horn and the Bay of Success. On August 26, 1768, the Endeavor sailed from Plymouth, England, commanded by Cook. The ninety-four-person crew, which included botanists, astronomers, sailors, artists, and servants as well as various livestock and two greyhounds,

was headed to the “newly discovered” island of Tahiti in an attempt to observe the transit of Venus across the sun. The trip was sponsored by Britain’s Royal Society, who hoped to use data collected by the crew to calculate the distance from Earth to the sun.

was headed to the “newly discovered” island of Tahiti in an attempt to observe the transit of Venus across the sun. The trip was sponsored by Britain’s Royal Society, who hoped to use data collected by the crew to calculate the distance from Earth to the sun.

Cook opted to take the route around Cape Horn to reach the Pacific. In early 1769, he anchored in what he called the Bay of Success, in the Strait of Le Maire. Joseph Banks, botanist and natural scientist aboard the Endeavor, led a fateful expedition inland to gather plant specimens, which stranded his group in cruel weather. Two men died. Afterwards, the expedition continued in a southwesterly direction, eventually passing Cape Horn with little danger.

Bonne, the Royal Cartographer of France, pays detailed attention to shifting perspectives in his maps. Topography looks different yet the same. Explorations are at once precise and mathematical as well as unpredictable, uncertain. In response, Steck’s piece considers logic problems around networks in nature, how numbers guide but also fail travelers, unseen elevations, changing climates, gaps of sight—all the fickle effects of external navigation on internal navigation. —NL

Terese Svoboda’s “Five Beards Not Counting the Goats’” is a journey waylaid, so it makes sense that it would be set in and among limbo: in a castle “looking across at what was probably the border of Switzerland” whose patrons speak a “German-Italian-English” pidgin. And while this castle has found its use in the modern day—making a neat profit off of American students abroad—its story is not unlike that of a ruinous, perhaps apocryphal castle known as Teufelsburg (“Devil’s Castle”) in the Swiss canton of Bern. As local legend has it, the Teufelsburg and the surrounding forest was the property of a mysterious noblewoman who lived there alone until she sold it to the town of Solothurn. One enthusiastic researcher, writing for the October 1913 edition of Pionier, the mouthpiece newspaper of the Bern school association, tracks this legend to a letter for the sale of property in the name of Elisabeth Gemmi, the financially-strained widow of the knight (ritters) Hermann von Bechburg, and then traces the building’s history through its days as a Medieval refuge. The same text also enjoys mythbusting the castle’s suggestive name, claiming it’s a mutation of one of the fortification’s previous owners, an 8th century Herzog named Thuitbold, it being common for “b” to shift to “f” as High German moved from Old to Middle to Early New. —NG

Terese Svoboda’s “Five Beards Not Counting the Goats’” is a journey waylaid, so it makes sense that it would be set in and among limbo: in a castle “looking across at what was probably the border of Switzerland” whose patrons speak a “German-Italian-English” pidgin. And while this castle has found its use in the modern day—making a neat profit off of American students abroad—its story is not unlike that of a ruinous, perhaps apocryphal castle known as Teufelsburg (“Devil’s Castle”) in the Swiss canton of Bern. As local legend has it, the Teufelsburg and the surrounding forest was the property of a mysterious noblewoman who lived there alone until she sold it to the town of Solothurn. One enthusiastic researcher, writing for the October 1913 edition of Pionier, the mouthpiece newspaper of the Bern school association, tracks this legend to a letter for the sale of property in the name of Elisabeth Gemmi, the financially-strained widow of the knight (ritters) Hermann von Bechburg, and then traces the building’s history through its days as a Medieval refuge. The same text also enjoys mythbusting the castle’s suggestive name, claiming it’s a mutation of one of the fortification’s previous owners, an 8th century Herzog named Thuitbold, it being common for “b” to shift to “f” as High German moved from Old to Middle to Early New. —NG

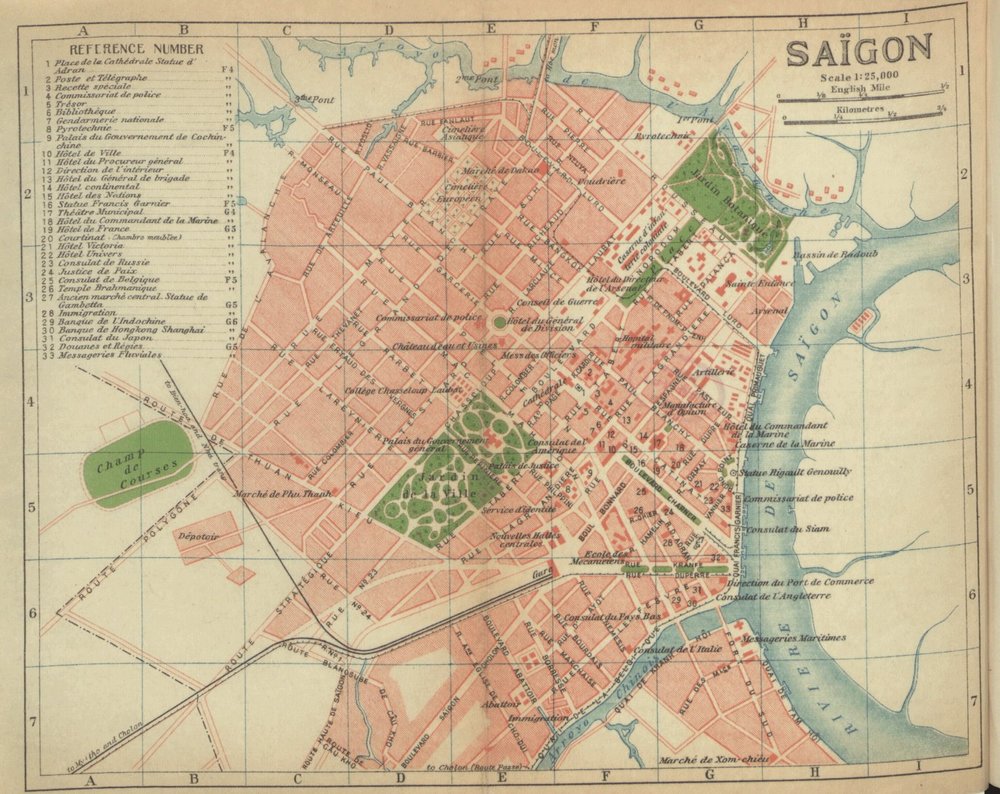

E.M. Tran’s “Soft Earth” responds to a map of Saigon while under French colonial rule. Cuong, Tran’s protagonist, is a refugee of the Vietnam War who finds himself navigating the unknown streets of Washington D.C., late at night. As Cuong remembers his life and his eventual flight from Saigon, the memory of the one city overlays and overlaps onto the other. The map of Saigon is a map of a fraught past. The French script that identifies street and place names speaks to the idea of replacement, both in the sense of a city that has replaced another and in the uncertainty of Cuong’s present moment, of his new and unforgiving place. —TMyL

E.M. Tran’s “Soft Earth” responds to a map of Saigon while under French colonial rule. Cuong, Tran’s protagonist, is a refugee of the Vietnam War who finds himself navigating the unknown streets of Washington D.C., late at night. As Cuong remembers his life and his eventual flight from Saigon, the memory of the one city overlays and overlaps onto the other. The map of Saigon is a map of a fraught past. The French script that identifies street and place names speaks to the idea of replacement, both in the sense of a city that has replaced another and in the uncertainty of Cuong’s present moment, of his new and unforgiving place. —TMyL

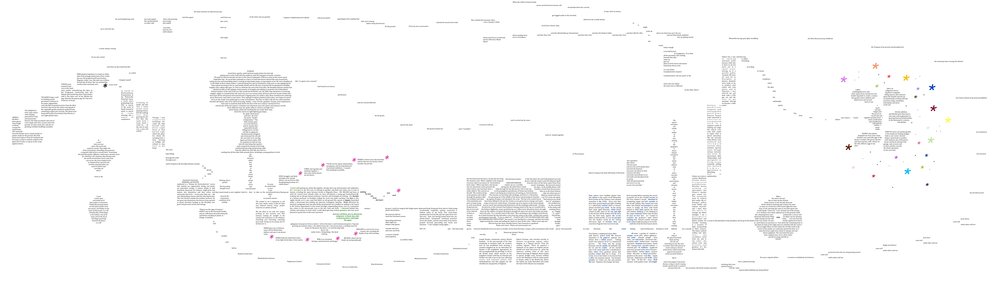

In Marco Wilkinson’s “A Gardener’s Education (Plant Body)”, the author creates his own map. Wilkinson had the following to say about the composition of his visual essay:

“At some point, I saw that the 8.5" x 11" frame of the page (and the page layout on my computer screen) was one of the instrumental factors shaping what I was writing. It was setting up expectations without my even realizing it. First in a piece called "Succession" (published online by Seneca Review) and now in this piece, I wanted to see what would happen if I let go of that framing constraint. This piece, ‘A Gardener’s Education (Plant Body),’ measures out to be about 9 feet by 3 feet. It has a nearly identical counterpart, an ‘Animal Body’ version that folds back into tidy paragraphs inside the frame. Commas and punctuation do the work of emphasis and rest, but seem a poor substitute for the gargantuan visual rhythm waiting beyond the nearly invisible received frame of 8.5" x 11".” —TMyL

L. Ann Wheeler’s “Three Migrations” asks, What is more than erasure? Migration patterns of animals can be mapped and arced, but also they are changing, subject to human interference—like study. To that end, Wheeler takes the cool, functional descriptions in Paul Mirocha’s world migrations map, a world streaked by the common barn swallow, and, narrowing even more selectively, morphs them into something else entirely. —NL

L. Ann Wheeler’s “Three Migrations” asks, What is more than erasure? Migration patterns of animals can be mapped and arced, but also they are changing, subject to human interference—like study. To that end, Wheeler takes the cool, functional descriptions in Paul Mirocha’s world migrations map, a world streaked by the common barn swallow, and, narrowing even more selectively, morphs them into something else entirely. —NL

Jenny Xie’s “Tessa Comes to Be Alone” responds to a 1914 map that measures isochronic distances from London. An isochronic map connects a series of points that occur or arrive at the same time, relative to a single point on the map. And so here, a red swatch indicates a five days’ journey to London, a pink swatch indicates ten, and so on and so forth. Isochronic maps are important measures of the history of travel—of how distances change over time, of how the impossible can come to feel deliciously possible, a matter of great concern to Xie’s protagonist Tessa. —TMyL

Jenny Xie’s “Tessa Comes to Be Alone” responds to a 1914 map that measures isochronic distances from London. An isochronic map connects a series of points that occur or arrive at the same time, relative to a single point on the map. And so here, a red swatch indicates a five days’ journey to London, a pink swatch indicates ten, and so on and so forth. Isochronic maps are important measures of the history of travel—of how distances change over time, of how the impossible can come to feel deliciously possible, a matter of great concern to Xie’s protagonist Tessa. —TMyL

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.