Legend

Underworlds

The appeal of an underworld is its subtext. Here lies the almost boundless potential for value: tap into the right spot and you uncover a hidden network, a system of meanings to inform the plot above.

Take the movie The Core (2003), for example. It’s the usual stuff. The earth has stopped spinning so the US government must assemble a ragtag crew of terranauts, as they’re called, to drill beneath the earth’s crust where they will detonate a series of nuclear missiles and restart the earth’s rotation, thus saving the planet. Their drill is named Virgil (get it?), an object that’s part-worm, part-spaceship, and entirely penile. It’s captained by Hilary Swank, a headstrong astronaut. The crew’s leader is Aaron Eckhart, a geology professor and lantern jaw. DJ Qualls plays a hacker (handle: Rat) who sells his services for “an unlimited supply of Xena tapes and hot pockets.” The Core is not a good movie.

One of the arguments for watching a crappy movie like The Core is that although it seems unworthy of our attention, it actually points to a larger, latent state of mind. A subtext. It’s that old, writing cliché about the iceberg, about how much a subject sticks out of the water and how much lurks underneath. The argument goes that, buried in The Core, we might our contemporary society’s fears and mores, preoccupations which a large and powerful industry has calculated and sold back to us, thus both enforcing and reinforcing the values that have led us to the movie in the first place.

So, what does The Core tell us about us? There are several scenes of global disaster (pigeons turn into homing missiles, pacemakers stop working, the Golden Gate Bridge buckles and snaps), yet hardly an explosion and never an intentional act of terror. Could this be because, just two years after 9/11, the filmmakers thought it more palatable to show us a natural disaster scrubbed clean of complex human agency? Or consider the moment the earth’s center stops spinning because a secret weapon built by the U.S. military as an act of deterrence—it’s named D.E.S.T.I.N.I.—has led to terrible, unforeseen consequences. You might say this is just dumb movie physics. But is it perhaps instead a subtle condemnation of contemporary U.S. interventionist policy, The Core released just a prescient eight days after the invasion of Iraq? Does reading into something so shallow inevitably lead us into diving in too deep, especially knowing that the only way to get through The Core is to be a little bit high?

There is no one way to understand the meaning of an underworld. It might mirror our world, like Italo Calvino’s Eusapia, or reorder it, like Dante’s concentric circles. It shows a past or a future, a hell or a home, an archaeology or a teleology. Sometimes, an underworld’s allure is its trap: it promises us a new world, but reveals only what we already tend to think. We mistake confirmation bias for uncovered knowledge, the miracle that we are seeing it at all undone by our only seeing it from one perspective. We remain trenched, entrenched.

Other times, an underworld presents us with a problem—a D.E.S.T.I.N.I.—we can no longer disregard. A story begins when what we’ve been ignoring for so long makes itself as inevitable and as obvious as the moment in The Core when, in the obligatory meta-wink before a bumpy ride, a character says, “Hang on. This isn’t going to be subtle.”

The best part about the film is Stanley Tucci. Isn’t this the case for all Stanley Tucci movies? He plays a preening celebrity scientist documenting the voyage for posterity. He’s also the only real character present, besides maybe Swank, if we’re going by the maxim that to be real a character must change with pressure over time. In his final scene, Tucci sits trapped in a compartment of Virgil with a nuclear bomb that’s about to blow. He’s an ambiguous character. You know this because he smokes and has a weak chin. D.E.S.T.I.N.I., it turns out, is largely his fault.

As he sits, Stanley Tucci narrates his final moments into a tape recorder. “For here, in the great unknowable,” he declares, “Man can come to know the most important thing of all—himself. He can understand…” He stops. Then he trails off. He puts down the tape recorder. The cigarette droops from his mouth. He shakes his head and then (just imagine the stage direction) remarks with wry realization: “What the fuck am I doing?” He laughs and laughs some more, in hysterics at the meaninglessness of his act. The camera pans out to the countdown; it’s at 3, 2, 1, 0. Then there’s some cheesy special effects.

The irony is that at the very moment Tucci drops the pomposity of “knowing himself” in “the unknowable,” he does actually come to know himself. He delivers his last line—and last laugh—in a voice he’s never used before. At the same time, this voice sounds much more natural. He loses his shell and, hang on, finds his core.

The result will be a lot more subtle, but that’s what we hope these contributors to Underworlds will do for you: be the voice that was always down there, waiting below, the voice you’ve never heard before, the one that asks, when the seconds are counting down and the cheap CGI is waiting to kick in, just what the fuck we are doing.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to contruct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

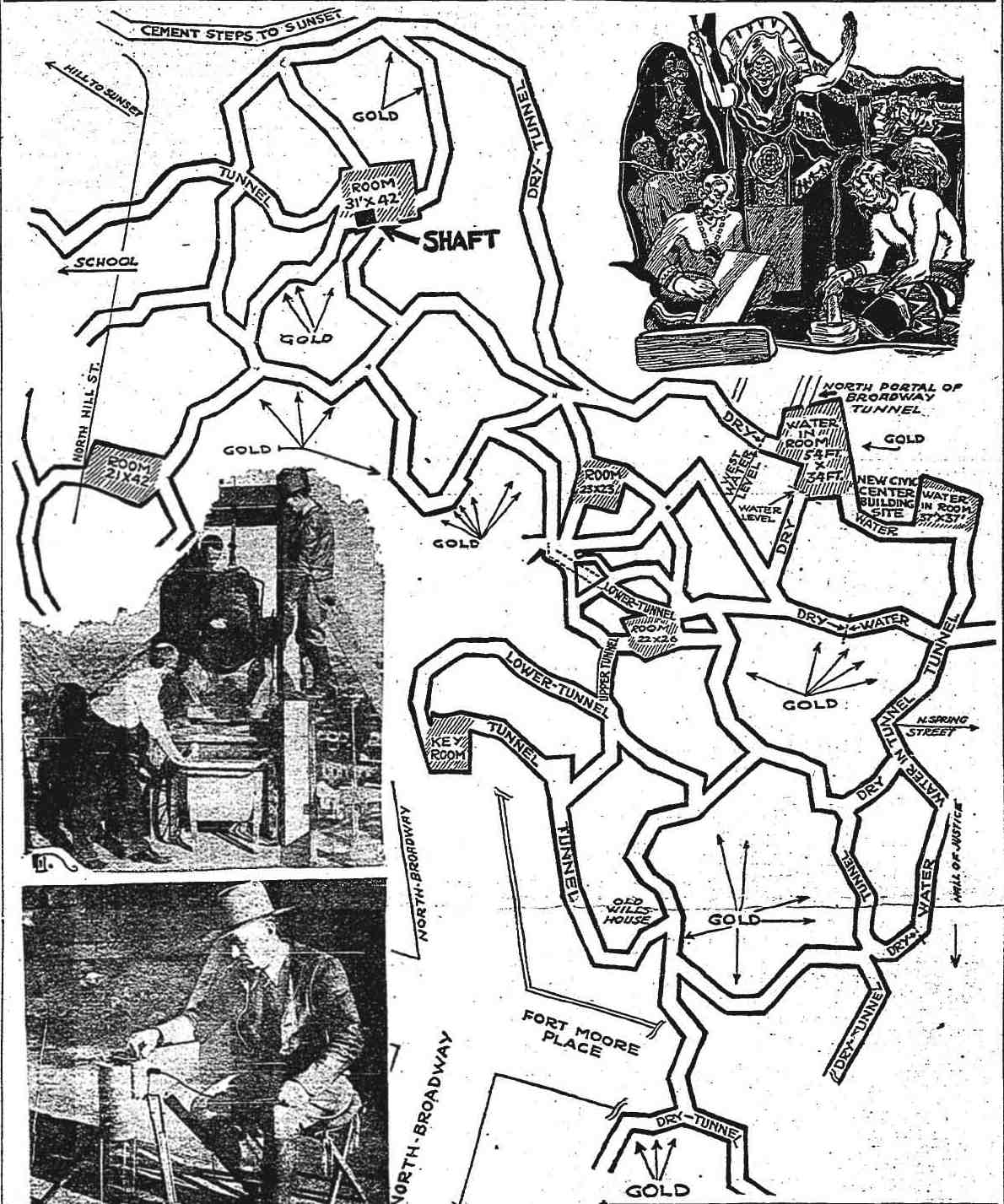

Caren Beilin’s “On a Printout of the Los Angeles Underground ‘Lizard People’ Tunnel Map (1934) in 2016” is exactly what its title describes. As the story goes, 5,000 years ago, a violent meteor shower hit the Earth like “a huge tongue of fire,” forcing the Lizard People, “a race of humans further advanced intellectually and scientifically than even the highest type of present day peoples,” to take shelter beneath the Earth’s crust. They lived there, forming cities connected with a vast network of tunnels carved by “mysterious chemicals.” One of the cities was beneath present day downtown Los Angeles, under Fort Moore Hill, and it was here that they buried untold quantities of gold.

5,000 years ago, a violent meteor shower hit the Earth like “a huge tongue of fire,” forcing the Lizard People, “a race of humans further advanced intellectually and scientifically than even the highest type of present day peoples,” to take shelter beneath the Earth’s crust. They lived there, forming cities connected with a vast network of tunnels carved by “mysterious chemicals.” One of the cities was beneath present day downtown Los Angeles, under Fort Moore Hill, and it was here that they buried untold quantities of gold.

Upon hearing this legend in 1933—in the midst of the Great Depression—a geophysicist named George Warren Shufelt dedicated himself to unearthing this gold. Using two ancient sheepskin maps and an x-ray machine he developed himself, he mapped the path to the treasure, a map the Los Angeles Times printed in their January 29, 1934 edition as part of the article, “LIZARD PEOPLE’S CATACOMB CITY HUNTED.” Though he dug down 250 feet, Shufelt he never discovered the tunnels, nor has any other treasure hunter. The gold, if it’s to be believed, is still out there. Same for the Lizard People.

Brian Conn & Michael Stewart’s “M2 The Temple of Dreams” is an adaptation of a Dungeon & Dragons campaign, both in process and product. Each of the six color-coded narrative streams represents a different crawl through the same dungeon, The Temple of Dreams, a series of nine named rooms (listed below along with information about their corresponding art).

1. Room of Blood - A medical illustration showing the veins. Anonymous; England; 13th century, late. From the Bodleian Library, Oxford University

2. Room of Visions - A lithograph by August Guy de Vaudricourt, "Surgery to correct strabismus, involving the division of the internal rectus of the right eye." Plate XLIX in Joseph Pancoast's "A treatise on operative surgery..." From the Wellcome Library, London.

3. Room of Earth - A detail of the only quadruple-folio folding leaf (68v) in The Voynich Manuscript, an anonymous manuscript from the Middle Ages. From the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

4. Room of Roots - An illustration of Yggdrasil from Northern Antiquities, Oluf Olufsen Bagge's 1847 translation of the Prose Edda.

5. Room of Past - An unnamed map of the Pacific attributed to Marco Polo (c. 1290). From the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C.

6. Room of Hymns - A detail of a motet from the Lansdowne Archives 462 f. 50v. From the British Library, London.

7. Room of the Foot - An anatomical sketch of a human foot by Clorion (aka Martha Chase Owen). Collected by Alexander Burnett in 1830. From the National Library of Medicine, Washington D.C.

8. Room of Nectar - An apiary from the Tacuinum Sanitatis, a medieval handbook on wellness based on the Taqwin al‑sihha تقوين الصحة ("Tables of Health"), an eleventh-century Arab medical treatise by Ibn Butlan of Baghdad.

9. The Burial Chamber - An illustration of the mouth of hell. From the Winchester Psalter (c. 1841) archived in the British Library, London.

The map on the title card is one generated using Dizzy Dragon’s Geomorphic Dungeon Adventure Generator.

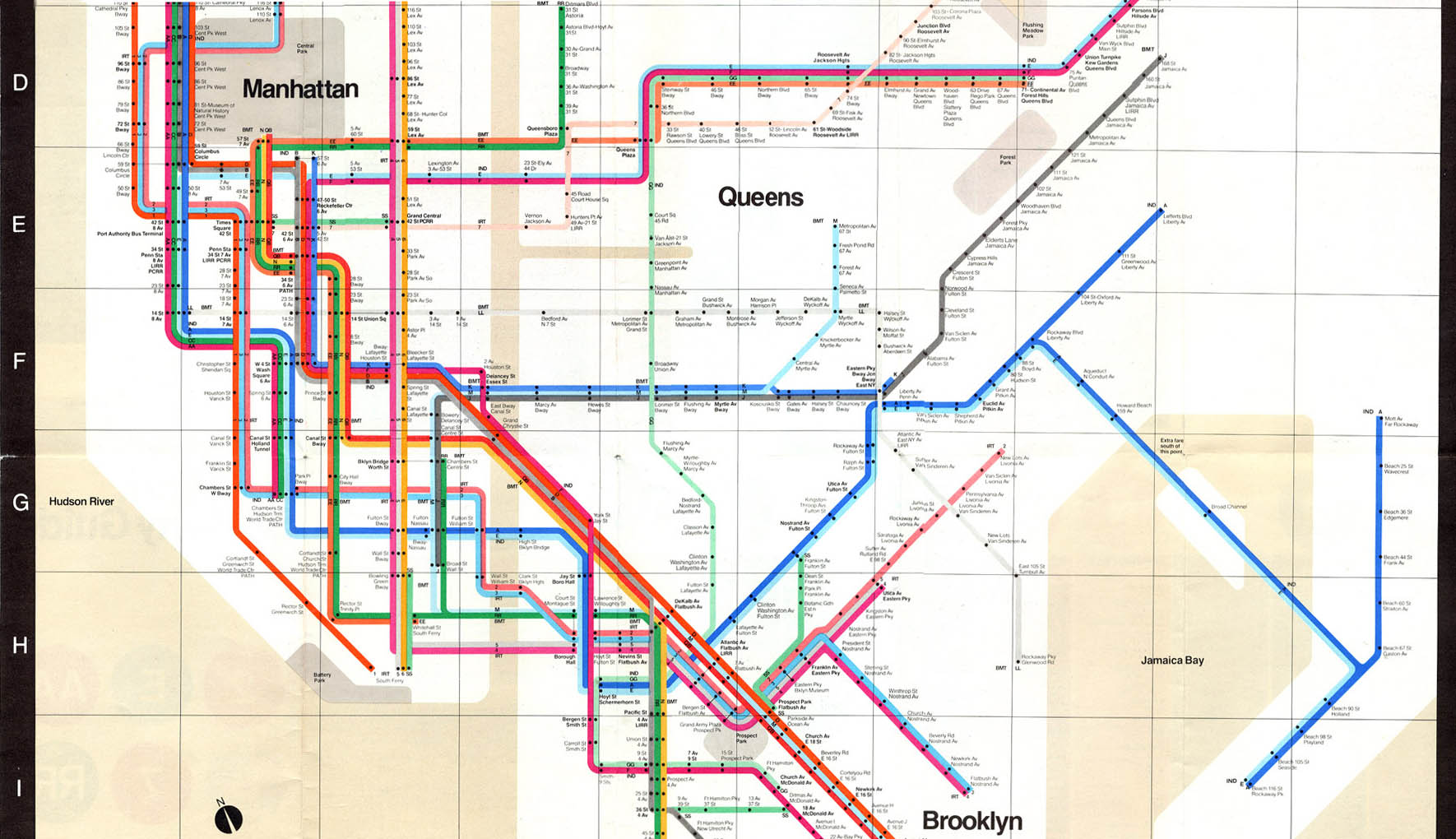

Douglas Degges and Chelsea Werner Jatzke’s “Borough Body” is a collection of two maps of the New York City Subway system—one visual, one textual, both inspired by the specific abstraction of the official NYC Subway maps. The map on the title card is perhaps the most infamous, having incurred many New Yorkers’ outrage when it was initially published in 1972 because the designer Massimo Vignelli stressed clarity over geographical accuracy. It has, however, gone onto define the way the subway system has been represented ever since.

Douglas Degges and Chelsea Werner Jatzke’s “Borough Body” is a collection of two maps of the New York City Subway system—one visual, one textual, both inspired by the specific abstraction of the official NYC Subway maps. The map on the title card is perhaps the most infamous, having incurred many New Yorkers’ outrage when it was initially published in 1972 because the designer Massimo Vignelli stressed clarity over geographical accuracy. It has, however, gone onto define the way the subway system has been represented ever since.

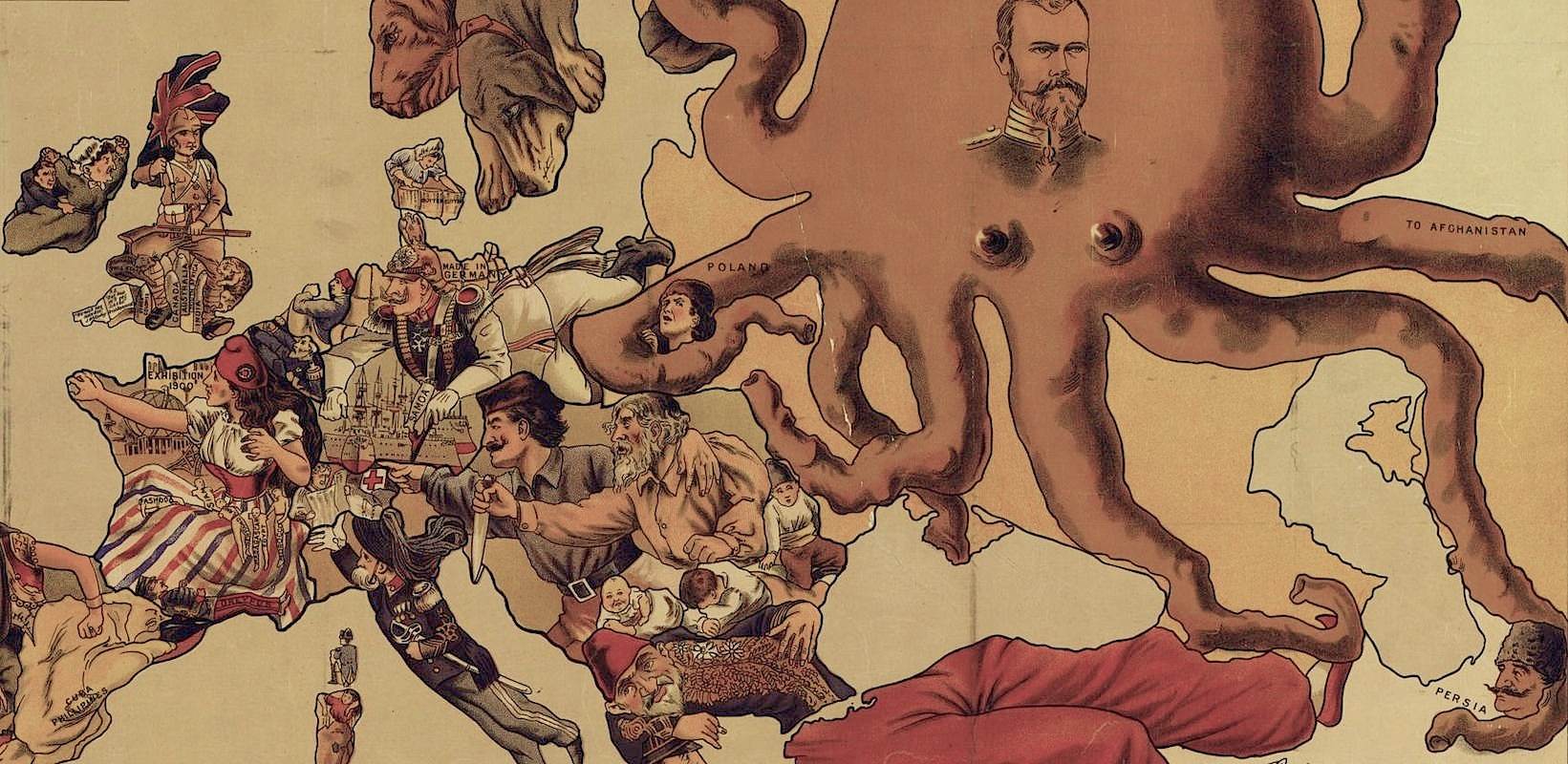

Madeline Gobbo and Miles Klee’s “It Is Valiant to Be Simple” takes place in the alternate reality suggested by a series of Late Victorian serio-comic maps illustrated by a Scottish tax clerk, Fred Rose. These maps represent the geopolitical attitudes Rose and his fellow Britons had towards neighboring nations and their dependent territories.  Europe is depicted as an imbroglio of people and animals, a caricature for each political body. India is a tiger biting a British soldier’s leg. Norway and Sweden are dogs, sometimes barking, sometimes submitting.

Europe is depicted as an imbroglio of people and animals, a caricature for each political body. India is a tiger biting a British soldier’s leg. Norway and Sweden are dogs, sometimes barking, sometimes submitting.

For how reductive and flip these representations can be, they’re surprisingly detailed, both in draftsmanship and narrative. These maps depict Russia as an octopus, “each of its eight legs spell[ing] out a different political event or desire, primarily territorial advances on the Ottoman Empire and its surrounding states” (BBC). This paradox of dimensional flatness is perfect for the octopus, which hides from predators by camouflaging itself as the ocean floor. The octopus is also a predator, as Madeline captures in her accompanying illustrations, constricting prey with its tentacles. The story is like this too, posing as outmoded genre fiction to mask an invisible southern hemisphere, one that comes from out of nowhere to grab you.

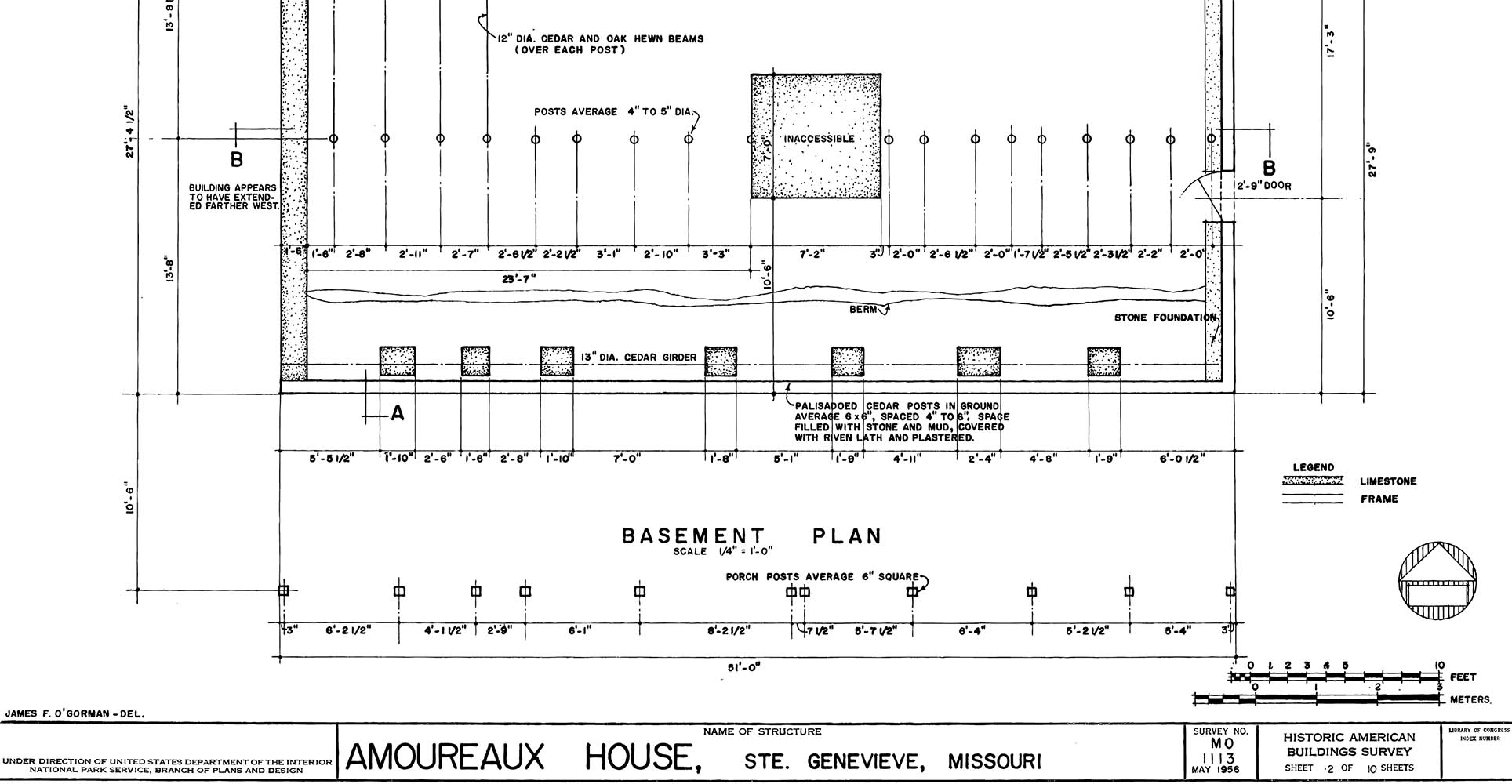

Micah Dean Hicks’s “The Carpenter and the Beast of Teeth” maps the Beauvais Amoureaux house in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. The house was built in 1793 and is one of five remaining poteaux-en-terre buildings left in the United States. Poteaux-en-terre, or post in ground, or earthfast, refers to a method of construction where a roof-supporting post is set directly into the ground, instead of a concrete footing or foundation. This method, popular among French colonists, has been practiced since the Neolithic period, though it is known as an “impermanent” form, the assumption being that it will do in the short term until a sturdier structure comes along.

Micah Dean Hicks’s “The Carpenter and the Beast of Teeth” maps the Beauvais Amoureaux house in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. The house was built in 1793 and is one of five remaining poteaux-en-terre buildings left in the United States. Poteaux-en-terre, or post in ground, or earthfast, refers to a method of construction where a roof-supporting post is set directly into the ground, instead of a concrete footing or foundation. This method, popular among French colonists, has been practiced since the Neolithic period, though it is known as an “impermanent” form, the assumption being that it will do in the short term until a sturdier structure comes along.

Credit to the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, MO-1113, for the use of this image.

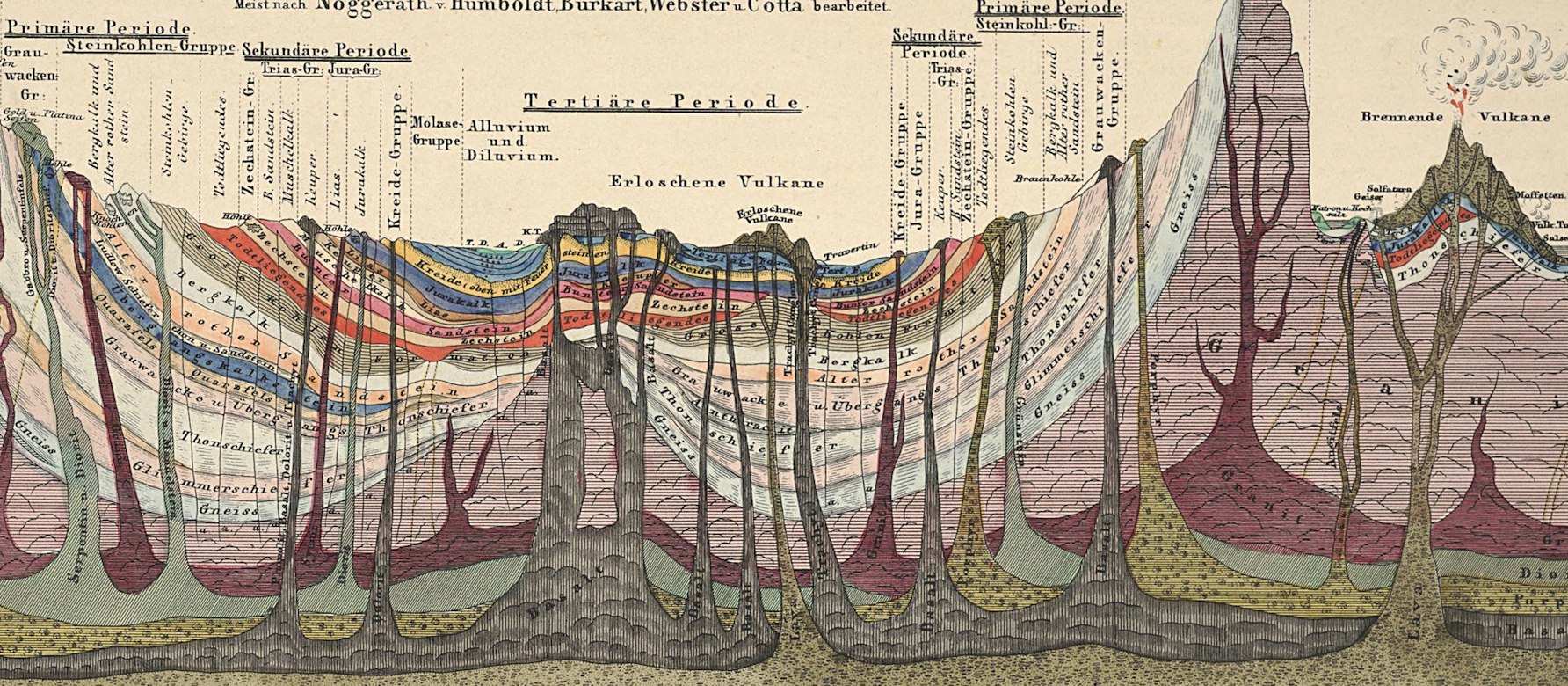

Kelly Luce’s “Cross-Section, West Texas” is a response to the map “Idealer Durchschnitt der Erdrinde” (“Ideal Cross-Section of the Crust”). Though this map was composed in 1851 by Traugott Bromme, it’s often attributed to Alexander von Humboldt who reprinted the cross-section in what turned out to be a famous and influential text, his treatise Kosmos in zweiundvierzig Tafeln mit erläuterndem Texte (“Kosmos in forty-two panels with explanatory texts”). Andrea Wulf, author of a new book on von Humboldt, The Invention of Nature, calls him “the most famous scientist of his age,” whereas Bromme was known more for writing travel guides intended to help German immigrants get by in the United States.

Wulf writes that “[c]onnection was the basis of Humboldt’s thinking. Nature, he wrote, ‘was a reflection of the whole’ and scientists had to look at flora, fauna, and rock strata globally” (128). Kelly’s story sees a surprising connection, the way the colorful strata in Bromme’s map resemble a cross-section of a human tooth.

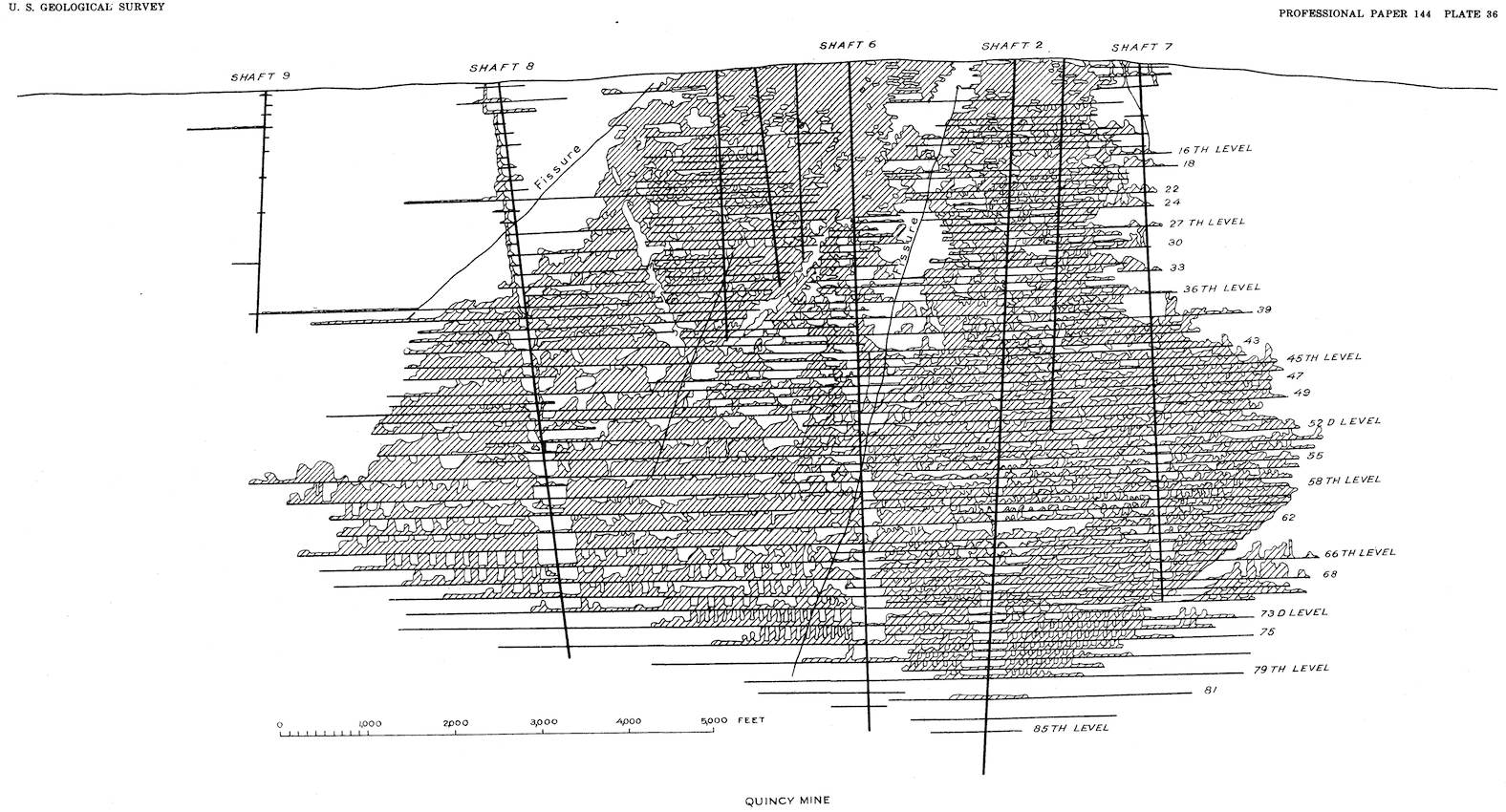

Ander Monson’s “Remainder” maps the Quincy Mine. The map in question is authored by the United States Geological Survey, a bureau of the Department of the Interior. Since the start of the millennium, the USGS has focused on a project called The National Map, a large-scale attempt to gather different facets of topographic information —it maps land by its structures, boundaries, hydrography, place names, transportation, elevation, and orthoimagery—and make these available to the public domain. Like many public endeavors, The National Map is crowdsourced; the National Map Corps are a group of volunteers who contribute to the project. You too can volunteer, the only requirements being an internet connection and a knowledge of the area mapped.

—it maps land by its structures, boundaries, hydrography, place names, transportation, elevation, and orthoimagery—and make these available to the public domain. Like many public endeavors, The National Map is crowdsourced; the National Map Corps are a group of volunteers who contribute to the project. You too can volunteer, the only requirements being an internet connection and a knowledge of the area mapped.

Nick Neely's “Into the Falls” maps both the history of Pawtucket’s development and the logistics of a trespass. This 1877 map of Pawtucket and Central Falls is not an underworld. Like many late 19th century maps, it presents a supernal, bird’s eye view, an overview of an overworld. Nick Neely’s essay, however, descends in several ways: it goes back in time to retrace and reimagine the history of Pawtucket’s development. And like many classic flâneur essays (Alfred Kazin’s A Walker in the City comes to mind), it zeroes in on the often overlooked evidence in a scene, in decided contrast to the sweeping panorama of the map.

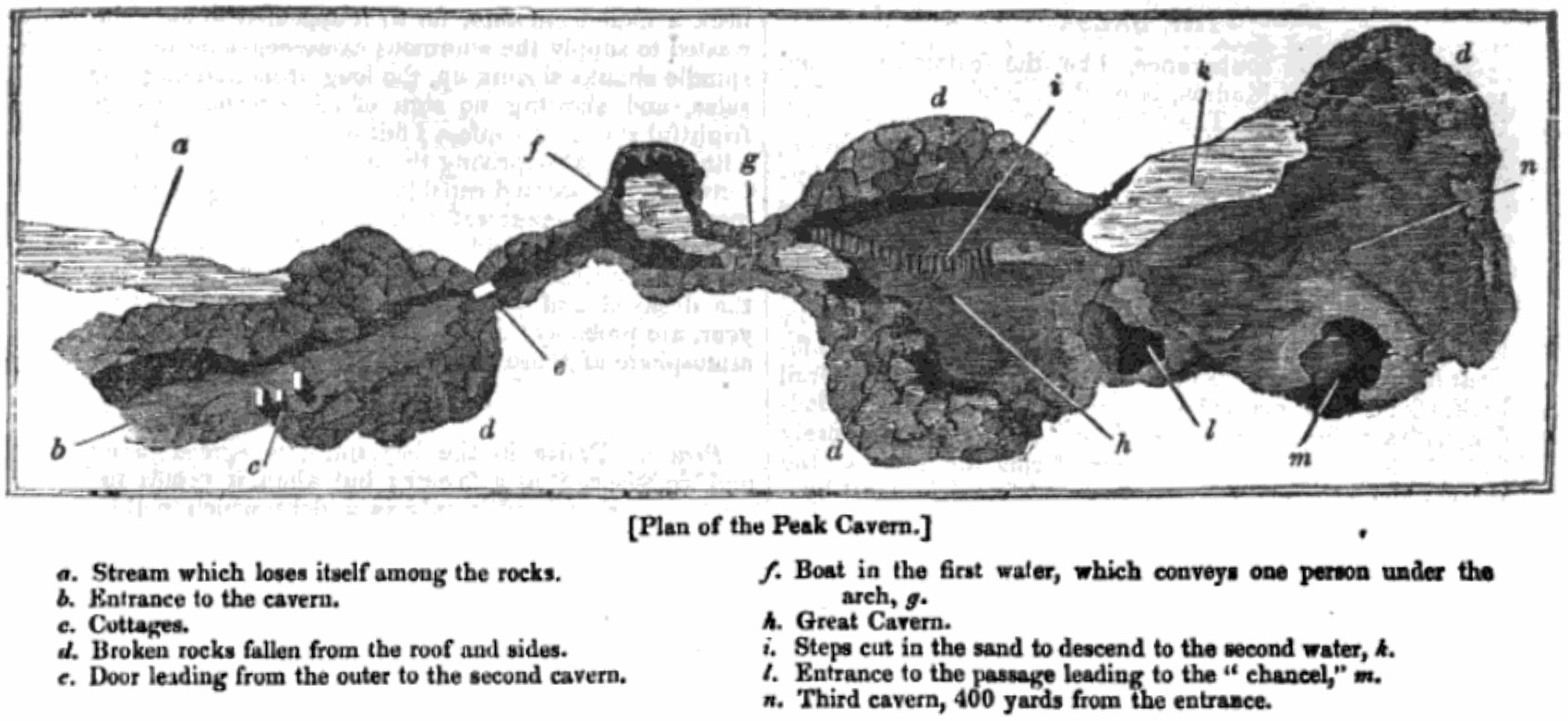

Emily Temple’s “Plan of the Peak Cavern” maps a cave in Derbyshire County, England. Peak Cavern has the largest cave mouth in the country and troglodytes made their home here until 1915. Legend has it that a secret language—known as a thieves’ cant—was developed in the cave by Cock Lorel, leader of the rogues, and Giles Hather, king of the gypsies. Historically, the cavern has been known as the Devil’s Arse as the sound of its draining flood water resembles flatulence. In A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain, Daniel Defoe refers to Peak Cavern as “the so famed wonder call’d, saving our good manners, the Devil’s Arse in the Peak.”

Emily Temple’s “Plan of the Peak Cavern” maps a cave in Derbyshire County, England. Peak Cavern has the largest cave mouth in the country and troglodytes made their home here until 1915. Legend has it that a secret language—known as a thieves’ cant—was developed in the cave by Cock Lorel, leader of the rogues, and Giles Hather, king of the gypsies. Historically, the cavern has been known as the Devil’s Arse as the sound of its draining flood water resembles flatulence. In A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain, Daniel Defoe refers to Peak Cavern as “the so famed wonder call’d, saving our good manners, the Devil’s Arse in the Peak.”

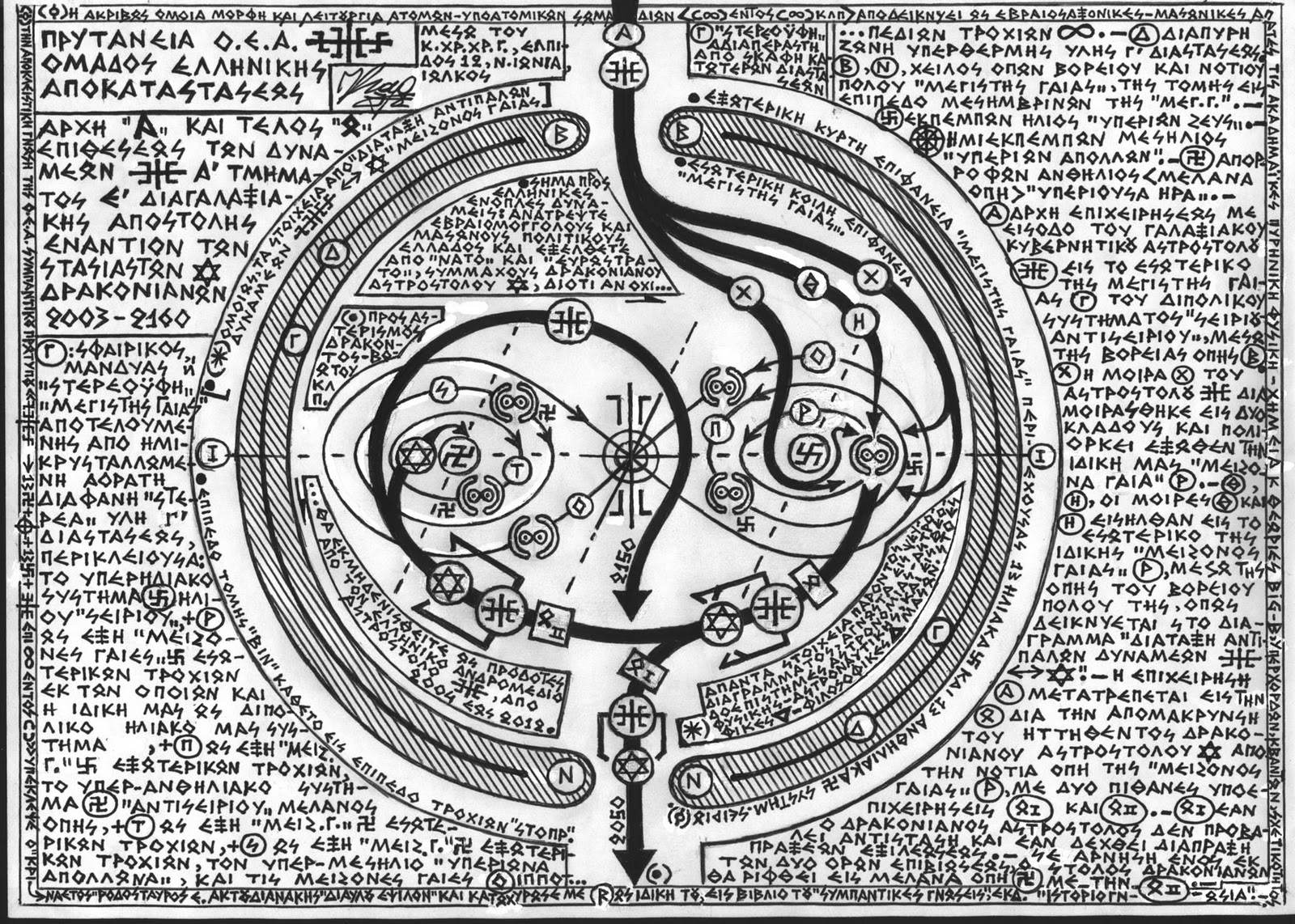

Hubert Vigilla’s “In Theory, Kitka” maps the belief in a hollow earth. Though there have been several prominent proponents of the hollow earth theory (perhaps most notably, Athanasius Kircher, who you may find more information about at The Museum of Jurassic Technology and its exhibit entitled Athanasius Kircher: The World Is Bound With Secret Knots), the author of this map is unknown.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way, their own personal underworld. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Other Underworlds

Our themes are territories too large to map in full, so we like to point you outwards, away from our particular interpretation. Below are some other maps of underworlds that we appreciate.

- Vu Tran’s Dragonfish, a map of Las Vegas’s underworld

- The criminal underworlds of Goodfellas, Infernal Affairs, Animal Kingdom, & Heat

- Marc Singer’s documentary Dark Days

- Will Hunt’s search for Minetta Brook, an underground river in Greenwich Village

- Matthew Neill Null’s Something You Can’t Live Without

- Italo Calvino’s Eusapia and other Invisible Cities

- Jeff Stark’s Before We Were Ghosts

- Book 6 of the Aeneid

- Jenny Boully’s The Body

- Brian Blanchfield’s essay "Understory"

- MAS Context Issue 28, Winter 2015 - Hidden

- Athanasius Kircher - Mundus Subterraneus - 1678

- Atlas Obscura’s Underground Channel

- The Orphic poetry of Mark Strand, Terrance Hayes, & Blas Falconer

- Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its many rabbit holes

- The Catacombs of Paris, Odessa, Znojmo, Rome, and Alexandria

- The drowned underground labyrinth in Hawara, Egypt

- Nuclear fallout shelters the US government explained and advocated for in pamphlets

- The wartime underworlds of Cu Chi, Somme, & the Atlantic Wall

- Subject A's Verses from the Underlands

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.

Underworlds was published August 5th, 2016.