I find myself loitering on the Main Street Bridge in downtown Pawtucket, Rhode Island, looking over the rail into the braided, writhing falls which continue to roar though tempered by a modest brick dam across its precipice. A fine mist billows up, especially early in the season or after a rain, and clings pearlescent to the spider webs woven between the bars of the rail, their elastic strands stronger pound for pound than the bridge's steel. This is what made Pawtucket and made America: the cascade, and the spinning. This is the fall line, our destiny, the division between fresh and salt water. Throughout the Northeast, mill towns rose up in just such locations, where the dense rock of the continent abruptly gives way to sedimentary coastal plain and the river finally cuts through. Energy is harnessed in the drop.

Just upstream stands the country's first water-powered factory, Slater Mill, which began to spin cotton into thread in 1793. The view to the mill from here, a distance of about a hundred yards, is just right for appreciation, lending the yellow clapboard building a pastoral, instead of an industrial, visage. It sits at the end of a slender park, across from the downtown bus station—all of it once shoulder to shoulder with mills, and all of those now gone, razed during a redevelopment project, except for Slater Mill. Two stories tall, the color of margarine, the mill has an ivory cupola that harbors a bell, which once would have served as the town's only clock, calling the millhands to consciousness and then, a half-hour later, to work. Now the building is a museum, its interior filled with all variety of cotton and textile machines, from Eli's gin to the carder to the iron throstle and mule that boys —and especially girls— risked their fingers to operate as they retied broken thread and swapped out spools. Through a glass window in the mill's floor, you can spy the water wheel, though not Slater's original, mired in mud like a skeleton in an archaeological pit—which it is. This behemoth caught the river to make these machines go. Slater's Mill was the first integrated, fully mechanized factory in the country, and so Pawtucket is considered the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution. From here, everything unspooled: interchangeable parts, factory labor, unfettered capitalism and its commodity culture. Our socks and underwear, our thousand thread-count sheets. Our American privilege, individualism, and particular isolation. On the Main Street Bridge, green canvas banners, themselves woven, hang from the imitation nineteenth-century lampposts: “Welcome to Historic Pawtucket,” they say in white, above a sketch of the mill.

Main Street curves lazily downhill to the bridge on both sides of the Blackstone River, because once this road was a cow path: an animal inclined to take a gentle route to chew its cud midstream. But long before the first English bovine was led off a ship in Jamestown in 1611, long before there was a bridge, these falls were already a crossroads, the way around Narragansett Bay on foot, a nexus of trade and, in autumn, a cove at which to net and spear salmon. Passersby picked their way across the rocks when the river was low, or across the frozen cascade in winter. Later this route across the falls became the horse-and-buggy turnpike to Boston and, eventually, Pawtucket's famed Main Street during its glorious heyday, which lasted well over a century until the Great Depression swept textile manufacture south.

From the north rail, you peer straight down to see the river pour over the dam and transform into wreathes of white on the black stone it has devoured and polished. The bedrock is riddled with potholes of various size, where stones from far up the Blackstone Valley have caught and turned countless scouring circles, each an unwitting pestle in its mortar. When the Blackstone tumbles over the falls, it officially becomes the brackish Seekonk River, an estuarial channel that, to start, is perhaps only fifty feet wide. Gradually it swells. Five more miles carry you clear to the open water of Narragansett Bay, to Fox Point, which Roger Williams rounded in his canoe to reach the Great Salt Cove he renamed Providence. Often I jaywalk across the wide lanes of Main Street Bridge and stare in that direction: downstream toward I-95, a green span that towers over the river a quarter-mile away as the bluffs taper and the Seekonk widens. The river corridor is mostly bound by granite blocks and concrete; its banks are fortified, paved, and built. Or they were. But once the falls would have roared unimpeded in spring and after storms, flooding this gauntlet and sweeping the woods, its leavings, into the Atlantic.

From the north rail, you peer straight down to see the river pour over the dam and transform into wreathes of white on the black stone it has devoured and polished. The bedrock is riddled with potholes of various size, where stones from far up the Blackstone Valley have caught and turned countless scouring circles, each an unwitting pestle in its mortar. When the Blackstone tumbles over the falls, it officially becomes the brackish Seekonk River, an estuarial channel that, to start, is perhaps only fifty feet wide. Gradually it swells. Five more miles carry you clear to the open water of Narragansett Bay, to Fox Point, which Roger Williams rounded in his canoe to reach the Great Salt Cove he renamed Providence. Often I jaywalk across the wide lanes of Main Street Bridge and stare in that direction: downstream toward I-95, a green span that towers over the river a quarter-mile away as the bluffs taper and the Seekonk widens. The river corridor is mostly bound by granite blocks and concrete; its banks are fortified, paved, and built. Or they were. But once the falls would have roared unimpeded in spring and after storms, flooding this gauntlet and sweeping the woods, its leavings, into the Atlantic.

I tilt my head down and stare into the churn, a sordid lace of foam that slides out from the bridge's overhang and, in the heat of the day, passes through my shadow carrying Coke bottles like fishermen's bobbers. Men and boys will drop a line—a long one—over this rail, or they climb down the river wall to a rock and cast their translucent, ephemeral arches toward the falls, and the bridge's hidden arches. After a flood, apples from upriver trees (or from a Costco bag) turn circles, and the snapping turtles slowly chase after them, nudging them forward with each bite. I've seen drifting carp, those barbeled teardrop monsters, and more rarely, around the time of a full moon, great coiling schools of pogy—a type of silver, foot-long baitfish of mythical numbers—waiting for the striped bass and bluefish to attack. And once a fisherman told me he caught a human arm and hand below the falls. It came up with its fingers half-curled. Some guy dumped in pieces by the mafia, probably. I thought about that story the time I saw a rubber glove, the kind for scrubbing tubs and toilets, rise and fall like a blue ghost on the dark surface.

Before long, I find myself ducking through a short, bushwhacked trail on the southeast corner of the Main Street Bridge to emerge on the river wall in a window of greenery. The Seekonk below the falls is flat and golden in the afternoon light; the brick hydroelectric plant across the river—also one of the first of its kind—casts a tiered, boxy shadow across the water. This sliver of ground on which I stand is mainly forgotten, given over to fishermen, weeds, and trash. Beneath my feet are the remnants of the railroad-grade rock thrown down to stabilize the denuded bank when most of the city’s downtown mills were razed under the pretense of redevelopment in the 1970s. But from old photographs, I know a massive mill once stood here on this wall, a mill so large it towered out of the picture—a five- or six-story monolith of brick. Now there are maples and invasive mimosa trees, and one lonely apple tree whose fruits I'm a little afraid to eat for fear of chemicals spilled into the soil. But I've sampled one, its tart juice.

The plan is to climb down and explore the falls. I've seen a few fishermen do it, so why not? It’s only eight or ten feet to the slab of raw bedrock that is the foundation for the wall’s tidy masonry. I glance around to make sure no one is watching from the Main Street Bridge or the opposite bank—no loafer like me. Then I stash my phone and the worn leather wallet my grandfather gave me in a stiff, sun-bleached yard glove lying in the dirt. There always seems to be one nearby: a glove on the sidewalk or in the gutter, flat as roadkill, missing its partner. Strolling around Pawtucket—around every city and town—I often see them and wonder whose hand it once held. I hide these leather fingers under a bush. The last thing I want is to fall in with these valuables in my pockets.

A few easy handholds and I scramble to the waterside without trouble. Here I’ve sometimes glimpsed other fishers casting under the eaves of the bridge, into the falls' aromatic backwash and the northernmost feet of the long Narragansett. A great blue heron hunts the cascade’s base, but when I descend it launches with a guttural sprock and glides crookedly to a downstream culvert. The river is hemmed in, both sides bound by sheer walls of fitted stone, their seams weeping with water and hanging purple flowers. Swallows nest in the embedded pipes that once jetted effluent.

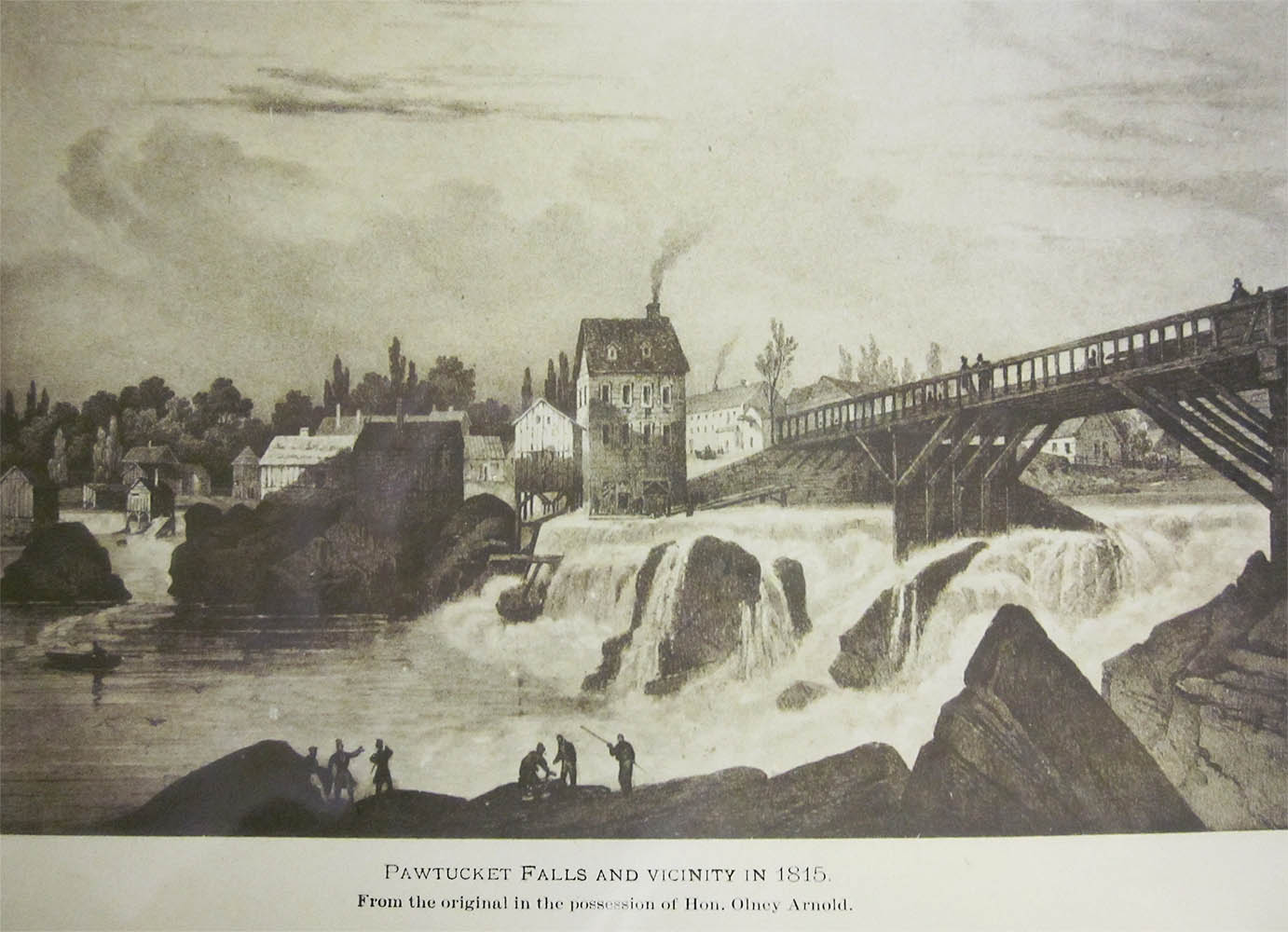

Over several centuries, this tip of the Seekonk has been made narrower, tidier; the falls were once much broader, with multiple channels and pour-overs that ebbed and flooded with the seasons and cloudbursts. In old etchings, you can see intimations that the cascade stretched out with early mills on islands and stilts midstream to capitalize on the natural flow. There was a secondary channel called Little River, which sluiced around an island with a large elm—the elms all but gone now from the East, too, because of disease. Little River provided an easy, more gradual passage for salmon and herring, but it is filled and buried now, and the little island is landlocked—in front of the bus station, I reckon—under years of cobblestone and pavement.

The infilling began when the first Main Street Bridge was erected in 1713—a bridge that was washed away every decade, or so, until it was built in stone in 1858. Little River was plugged by the bridge's approach, but the fish could still leap through notches in the main falls, that still tumbles and splashes before me with the Blackstone’s whole life force. However, Pawtucket’s first dam was built shortly after in 1718. Previously there had been only scrappy dams of cobble, gravel, moss, straw, and wood stuffed between the natural rock, and they extended only part way across to funnel water to a blacksmith’s forge or a saw. But all at once, a permanent dam atop the falls now raised its height several vertical feet from bank to bank, and the herring and salmon that forged inland were stymied, as they still are. Uniformity spells the demise of fecundity. But sometimes I like to imagine Little River and its fish still running right through downtown, flowing and fining through the traffic light at the intersection of Taft and Main; and perhaps you can still catch a glimpse of Little River during a summer downpour, when the streets suddenly gush with waves collected down the old cow path.

Resolve builds, swells, within me. I confront the skinny ledge of concrete protruding from the bridge's poured foundation, a ledge I've seen several fisherman traverse with bass swaying silver in hand. The ledge isn't as wide as my hips, but it's a couple inches wider than my size-thirteen feet, and it turns a gentle corner around the bridge’s footing toward the falls. Seems easier—safer, I think—to keep my heels toward the wall with my toes toward the river, on the very edge. My high center of gravity presses my back into the foundation as I begin to sidestep, and the cotton of my T-shirt scrapes across the concrete’s raised skin, its hard goosebumps tinged with dry, pale algae.

If I were to fall, it would be about ten feet into dark, organic water, and possibly onto hidden rocks. If I were to lose my balance—who could help but imagine it?—I would push off at the last second and try to plunge farther from the river’s edge, away. The mind flickers between optimism and pessimism, never quite registering which is which. Between present and future, and past: Just for a thrill, boys used to jump into the Seekonk from the mills over the river. Before those mills, men swam out to Fish Rock, a famous outcrop midstream below the falls, with spears to thrust into the glossy backs of salmon. But the riverbanks in Pawtucket were squeezed until even this totemic stone was nearly swallowed around the turn of the nineteenth century: The rock became a cornerstone of the Bridge Mill Hydroelectric Plant, and now you can see just a portion of this striated, sparkling form, which emerges from the river wall like the dorsa of a whale. Red sliders bask there sometimes, and once, looking down on this former island, I watched as two rats climbed a foot or two up the dry racemes of a weed to eat the seed like withered corn on the stalk.

If I were to fall, it would be about ten feet into dark, organic water, and possibly onto hidden rocks. If I were to lose my balance—who could help but imagine it?—I would push off at the last second and try to plunge farther from the river’s edge, away. The mind flickers between optimism and pessimism, never quite registering which is which. Between present and future, and past: Just for a thrill, boys used to jump into the Seekonk from the mills over the river. Before those mills, men swam out to Fish Rock, a famous outcrop midstream below the falls, with spears to thrust into the glossy backs of salmon. But the riverbanks in Pawtucket were squeezed until even this totemic stone was nearly swallowed around the turn of the nineteenth century: The rock became a cornerstone of the Bridge Mill Hydroelectric Plant, and now you can see just a portion of this striated, sparkling form, which emerges from the river wall like the dorsa of a whale. Red sliders bask there sometimes, and once, looking down on this former island, I watched as two rats climbed a foot or two up the dry racemes of a weed to eat the seed like withered corn on the stalk.

After fifteen feet, the ledge turns a corner, an easy reflex angle into the shadow. Hardly breathing, I inch along, staring at my feet, until I step onto a landing of bedrock under the bridge and close to the reverberating falls. In this stone is a large hole, about three feet wide. From above, I had assumed this hole was man-made, perhaps drilled for an old bridge pier. But clearly it was the river that bore through. How powerful the Blackstone must have been before this dam—and all the dams upriver that control the flow. Powerful still. The hole’s smooth interior, the way its curvature holds the afternoon light, reminds me of Southwest canyons, of Zion’s walls. From the bank above, the rocks beneath the bridge don’t seem especially large, but in fact they are immense and quite angular: their contours sculpted, but somehow rough to the touch, slightly gritty, like sandstone. Each is a prow traveling downstream, but together they are a rampart. The river has honed them as if to guard against the trespass of all but fish.

There appears to be one route upward, just one, over a slight overhang. If I climb up, it will have to be while leaning backward somewhat precariously. But I’ve come this far. Shake off those nerves, gather yourself. I find a few handholds, and then I throw my shin, painfully, onto the rock’s top as if climbing awkwardly out of a suburban pool. Someone stronger, more flexible—a true climber —would have managed this ascent more gracefully, and it dawns on me, even as I climb, that I may have trouble getting down. I don’t dwell on that now.

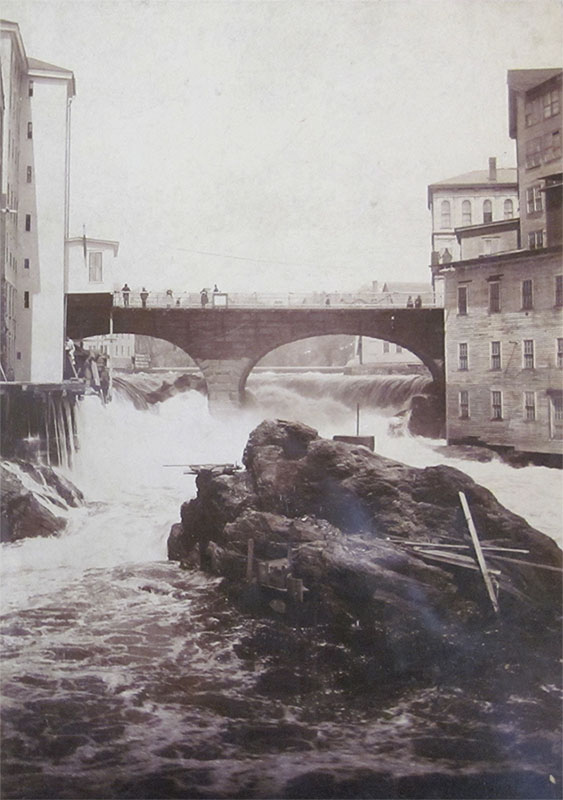

In the language of the Narragansett tribe, Pawtucket means “place of falls,” and finally I have reached the pulsing heart of that place, a crossing now umbrellaed by Main Street Bridge and made almost subterranean, like a river going briefly underground. The spray of the cascade fills this basement and carries the dim light throughout the space. A gaping pipe projects from the bridge’s concrete foundation, completely rusted, orange water trickling from it and draining to the Seekonk. The underbelly of this bridge in part tells the story of this town: the north side, directly above the falls, is supported by picturesque pillars and arches of quarried granite, a single lane designed for mules and carriages. The other, downstream side rests on poured-concrete abutments and horizontal steel beams, painted green—also beautiful in its rigid way, with rafters for pigeons—added in the 1960s to double the bridge’s width as traffic increased. The bridge is a mongrel, its two halves built one hundred years apart.

Further into the interior, in a dank corner, is a navy blue sweatshirt that's soaked through and plastered over rock. GAP, reads its chest, in bold white, as I unfold it. Who left it, and why? Or was it washed here? Suddenly I feel the presence of those who’ve crawled into the falls before me: The person who wore this clothing. The men who built this sturdy stone bridge, and others who fastened the wooden spans washed away by floods. Other, earlier people crouched in the sunlight to lance or net fish as they charged, quivering, up its myriad channels. Now the falls is a redoubt from sun, cut off from all but the adventurous or foolhardy. Not even the fish can access its summit anymore. Only the glass eels creep up and over the dam on their bellies, each like a living snippet of fishing line breathing through translucent skin.

And I think of the numbers who have walked or driven over these falls and how the world they knew has changed. Of those who picked their way across the raw rock, and the animals that carted wagons of coal and lumber across a rickety, trembling bridge to feed the mill's furnaces. Of the narrow-gauge trolleys rolling, past men in bowl hats and women in gowns, before the city went to seed, and the RIPTA buses that now roar across and palpably shake the bridge’s southern half, its new side, on its hot-and-cold expansion seams. I think of the towering highway bridge just downstream, which made this falls a backwater and no longer a key intersection in the Northeast: it cut the town in two in 1954 and helped divert business to larger malls and cheaper fields. Though that span of I-95 across the Seekonk soon will be torn down because of structural flaws and replaced with something even grander and, one hopes, longer lasting. But not as durable as stone.

I can go no further without getting my feet wet and risking disaster. So I sit, absorb the atmosphere. Under here is a wind tunnel, a rush of water and sound, a liminal perch. I hear nothing but falls, as it sheets over the dam and unravels down the sable rock in its long-worn grooves and tongues. Water that comes from Massachusetts, some of it all the way from Worcester, where the Blackstone begins before its wends forty-eight miles south to this drop. Like a tide that overran the falls, industry spread up the Blackstone and its tributaries until by 1830 the watershed was stitched with more than two hundred dams, each an impoverished replica of, an homage to, a natural cataract like this one. The Blackstone became known as The Hardest-Working River in America; eventually it also would be called The Most-Polluted River in America. Clumps of sudsy foam as large as icebergs—many as colorful as a strand of the rainbow—once slumped over these falls from the dye houses and circled on toward the bay. The cascade would tumble a different hue every day, depending on the fashion.

In this moldering but somehow also fresh pocket of Pawtucket, the city has vanished except for the old Slater Mill upstream, which I can see framed between the dam and the bridge’s old granite arch as if through the opening of a tunnel: Inside that first beacon of American Industry, now restored and a museum, is a model of the essential machine that Samuel Slater invented—or rather replicated, since he stole the blueprint for it in his mind when he stole away from England dressed as a farmer. He was hired by Moses Brown, a wealthy Providence Quaker and merchant, to perfect the art and apparatus of cotton spinning. Slater famously said to Brown, "If I do not make as good yarn, as they do in England, I will have nothing for my services, but will throw the whole of what I have attempted over the bridge." But with the help of local craftsmen, he managed his spinning machine, which pulled the gauzy roving from spools to forty-eight spindles, the distance between its rollers precisely calibrated to stretch and entwine the fibers, but not too thin. This machine is called a "water frame" because it was powered by the river, but in operation it looks like nothing so much as a stylized waterfall, white threads cascading straight down well-designed channels—and ceaselessly if the factory is well-oiled. Slater's original machine now lives in the Smithsonian Museum, in storage.

Slater famously said to Brown, "If I do not make as good yarn, as they do in England, I will have nothing for my services, but will throw the whole of what I have attempted over the bridge." But with the help of local craftsmen, he managed his spinning machine, which pulled the gauzy roving from spools to forty-eight spindles, the distance between its rollers precisely calibrated to stretch and entwine the fibers, but not too thin. This machine is called a "water frame" because it was powered by the river, but in operation it looks like nothing so much as a stylized waterfall, white threads cascading straight down well-designed channels—and ceaselessly if the factory is well-oiled. Slater's original machine now lives in the Smithsonian Museum, in storage.

Other than this view of the mill, there is just my breath, the spray, and the musty smell of this cave with two mouths. Though the Pawtucket Falls may have been overshadowed by Slater’s water frame—though the falls has been harnessed, tempered, narrowed, blasted, and covered—it still moves me. The air quakes with moisture. It could still take your life if you were to slip. In some ways the feeling of its power is multiplied and enhanced by this low, man-made ceiling. As I try to take a few final notes, the mist quickly dampens the page and gradually turns its blue lines soft and see-through:

The giant snag, as bleached as a bone, that hangs over the dam and clearly won’t budge except for a hundred-year flood. The towering cottonwood it once was.

The small boulder by my feet, too heavy for me to lift, which is snug into its pothole. In a winter deluge, maybe it still gyrates, boring another hole, another window. Eventually it may fall through. For now it rests like an egg in a nest.

The hundreds of gnats, those little silvery wings, floating in small lofty pools, these rockbound puddles filled to the brim by droplets of spray.

The seconds pouring so relentlessly, and landing on my skin.

The extreme chill of this place. The need for a sweatshirt.

Boys get themselves into trouble. I have come to an impasse. I am stuck. Over and over beneath the bridge’s canopy, I endeavor to suspend myself from the rock overhang and drop down the passage I came up. But my grip is tenuous, and now I am afraid. Descending backwards just isn’t an option, so far as I can see: One mistake would mean head over heels, without a helmet, onto rock. No way to break my fall. No way to see the water fast rising. Over and over, I put the heel of my hands on either side of the notch I climbed through and attempt to lower myself. But the heels of my running shoes are too big and clumsy to find purchase on the slight toeholds I used on the way up.

My arms begin to quiver; my shoulders burn slightly. Over and over, I raise myself back up and sit on the edge, my heart pounding. No one knows I am here. I could yell at the top of my lungs and not be heard amid the tumbling echo of the falls.  My phone, wallet, and ID—with a picture of me as a fifteen-year-old—might never be found, hidden as they are in a crusty garden glove below a bush.

My phone, wallet, and ID—with a picture of me as a fifteen-year-old—might never be found, hidden as they are in a crusty garden glove below a bush.

I try to clear my mind, to think positively. Breathe in and out, and take in the downstream view of the hydroelectric plant built upon Fish Rock. The heron is still there, unconcerned, statuesque yet ruffled in slate-blue as it stares, like me, into the river. In and out, and then I suspend myself again, coming to terms with the creeping reality that I’ll have to jump seven feet or so to the initial rock ledge with the sculpted hole. Normally, this wouldn’t faze me, but the stone’s surface is wildly uneven and only a few feet wide. I’m worried I’ll stumble forward a few feet and plunge into the river: the image of broken teeth.

Somehow I must muster the conviction to let go, to let myself fall. I concentrate on the rock below, scrutinizing its ridges and divots. My mind is the trough of agitation below the cascade, but finally it produces the confidence, the resolve: Let go. Let yourself fall. This life is made of leaps, of innovation and risk and the consequences. Salmon and herring flashing over these stone heights, until they were barred by a dam. The spectacular rise of Pawtucket on the fortunes of cotton, and its decline at the hands of the automobile and, more generally, the economy it helped spawn. An economy that seeks the path of least resistance, sweeping jobs and fortunes downriver. And I land on my feet, pitching forward only slightly. And I take two leaden steps, somehow also wobbly with adrenaline, to a safer platform. And I am shaking like the bridge, like the falls-wracked air. And though I’ve brought a notebook, and I try to jot something, I can’t hold my hand steady, or a thought. The water revolves in its foamy basin and moves on.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Nick Neely’s debut collection of essays, Coast Range, is forthcoming in November from Counterpoint Press. His work has appeared in journals such as Kenyon Review, The Georgia Review, and Orion. He is now walking from San Diego to San Francisco, retracing the route of the first overland Spanish expedition into Alta California.

The Natural Bridge of the Rogue River

The Natural Bridge of the Rogue River, near Prospect, Oregon, is a spot where this rugged river goes underground for two-hundred feet. It disappears into a lava tube that once flowed with molten basalt like a vein on the stomach of Mt. Mazama, which blew its top to form Crater Lake. Of course, this natural bridge was used by Native Americans and settlers, and so it was a conduit for travel and cultural change. The Rogue River watershed is, also, one of my psychic underworlds, a hidden river that courses through me: Many of the essays in Coast Range are set in the Rogue country and, though not true, it seems I have dwelled there for a very long time.