Legend

Alaska

Lefty Frizzell’s “Saginaw, Michigan” relies on a narrative deception. The singer, “the son of a Saginaw fisherman,” is engaged to a woman whose wealthy father looks down upon his prospective son-in-law. To prove his worth, the singer travels to Alaska, where he strikes it rich in the Klondike and, upon returning to Saginaw, wins the father’s approval. The father, greedy tycoon that he is, convinces his son-in-law to sell him his claim and goes to Alaska himself. But it’s a trick: Our singer never found any gold in Alaska. He only wanted to get rid of his father-in-law so he could live in peace in Saginaw. In the last image we have of the father, he is digging in the “cold, cold ground,” searching for something that is not there.

Whether it knows it or not, the song traffics in many of the myths and misconceptions of Alaska. From the singer’s perch in Saginaw, Alaska functions as an imaginary space, a wild land where our hero may test his mettle and prove his worth, before returning to his polite, Midwestern blue-collar life and wife. Whatever exploitation the singer perpetuates—the ways in which he represents the plunder and colonizing of natural resources and indigenous lands—is a means to an end. Alaska may be wronged, but the singer gets his life right. The joke at the end depends upon another myth: That Alaska is empty, a blank map awaiting the pen.

It comes as no surprise that many maps of Alaska perpetuate that settler-colonial perspective: There is the totem pole in the lower right corner, the igloo in the top left, a lumbering bear in the middle, not too far from a gold mine. From this bird’s eye, the landscape is expansive yet traversable. There’s room for anyone, these maps suggest, which often means just the opposite. By what authority do they claim this? These maps do not acknowledge, of course, that the Aleut, Inupiat, Athabascan, Yuit, Tlingit, Haida, and other native peoples have stewarded the land depicted, throughout the violence and removal that such maps give rise to. That Alaska, despite its seeming inviolability as a political entity, is a recent state and a temporary one at that, one that hosts and is hosted by multiplicities of climates, ecologies, histories, languages, and peoples.

It comes as no surprise that many maps of Alaska perpetuate that settler-colonial perspective: There is the totem pole in the lower right corner, the igloo in the top left, a lumbering bear in the middle, not too far from a gold mine. From this bird’s eye, the landscape is expansive yet traversable. There’s room for anyone, these maps suggest, which often means just the opposite. By what authority do they claim this? These maps do not acknowledge, of course, that the Aleut, Inupiat, Athabascan, Yuit, Tlingit, Haida, and other native peoples have stewarded the land depicted, throughout the violence and removal that such maps give rise to. That Alaska, despite its seeming inviolability as a political entity, is a recent state and a temporary one at that, one that hosts and is hosted by multiplicities of climates, ecologies, histories, languages, and peoples.

For our twelfth issue, our contributors pick away at the thread of this perspective and, within the existing and ongoing plurality of voices, offer their own. Ernestine Hayes’ “Bury This Story” inhabits the old houses of Hayes’s life, the homes “invisible and unremarked” that linger “on any map of Juneau that acknowledges indigenous presence.” “Not all of them do,” Hayes adds. Piper Lane’s “Spillionaires,” a trio of linked stories, traces the ripples of the Exxon-Valdez oil spill upon a fishing community, from the “oil slicked seals and sea otters” caught in the seine to the men “who expect us to shut the hell up when anyone asks where we caught all those salmon.” Of her poem “Sea Change, Heavy from the West,” Abigail Chabitnoy writes, “When I think of Alaska, I think of home. But when I think of home, I do not think of Alaska,” and so here is a map in which “the people and their stories are the landscape.”

We are grateful to these authors for sharing this space with us, for allowing us within the grace and persistence of their language. We hope you find that space—a different kind of space—too.

-Thomas Mira y Lopez & Nick Greer

Maps

We ask our contributors to construct or respond to a map, but what defines a map and how a contributor chooses to interpret its territory will vary radically with each piece. Here is how things played out for each:

Abigail Chabitnoy’s “Sea Change, Heavy From The West” responds to a map by Sven Larson Waxell that, roughly translated, depicts “the Great Nordic Expedition off the Shumagin Islands.” Chabitnoy offers the following explanation of her process:

Abigail Chabitnoy’s “Sea Change, Heavy From The West” responds to a map by Sven Larson Waxell that, roughly translated, depicts “the Great Nordic Expedition off the Shumagin Islands.” Chabitnoy offers the following explanation of her process:

When I think of Alaska, I think of home. But when I think of home, I do not think of Alaska. At least, not immediately. Unless I'm already in a romanticizing frame of mind. This map was drawn upon Vitus Bering's first encounter with the Aleuts (or rather, the Unangan) of the Shumagin Islands. Bering's mission was twofold: to find a land bridge, and to fill in as much "white space" on their maps along the way. Instead of a land bridge, however, they encountered a people (several peoples in fact, though for centuries they would be lumped together as Aleuts and shuffled around the islands and Pacific coast of the Pacific Northwest as it suited their "benefactors"). Their presence and plight were—are—bound to the landscape, the sea, the "white spaces" on maps of Alaska. As an Unangan/Sugpiaq descendent born and raised removed from this landscape as a result of colonization, the people and their stories are my map home. I learn the land through them, what they have endured, what they have continued. The people and their stories are the landscape in this map. The coordinates, hardly legible, will not help one locate themselves by this map, will not allow me to locate myself by this map. But the man in the kayak, the man here illustrative of a people synonymous with water, with survival and resilience—he waits to take me where I must go to find the home I seek, to find my relatives.

The history of the Russian colonization and occupation of the Aleutian Islands and coast of Alaska that followed from this encounter is brutal and devastating. But it is also the history of a people that persists. And they do so through story and community. Not evident on this sparely drawn map, trying to hid just how much white space remains behind the superimposed age of the man in the kayak (an image still iconic of the region today even as another colonial force jockeys for that space) is a landscape that is at times violent, unforgiving, and unrelenting in its demonstration of geologic and meteorologic might—and yet also one that is beautiful, teeming with life, and bountiful enough to sustain a remarkable and resilient people to this day, despite the threats that continue to lap at the feet of indigenous peoples today. When asked by the Russians if the world had an end, the Aleuts told them no. No, there are those of us who set off a long time ago in search of the end, when we were young, and though we returned old, still we did not find it.

Mirri Glasson-Darling’s “On Alaskan Literary Cartography” responds to a 1983 topographical map of Barrow Point, as produced by the United States Geological Survey. The imagery recorded in the map was captured by Multispectral Scanner System (MSS), a line-scanning device used to produce satellite imagery as part of NASA’s LandSat program. Previous topographical maps of Barrow Point, such as a 1950 version prepared by the Army Map Service, used aerial photography, a process that became increasingly popular during the years before and after World War II as it allowed the mapping of military zones without the need to step foot in them. Indeed, this corresponded with an increase in the military-flown imagery of Alaska and Hawai’i. Aerial photography was lauded for providing “a straightforward depiction of the physical and cultural landscape of an area at a given time,” although the 1950 map of Barrow Point included a note in its fine print that “users noting errors or omissions on this map are urged to mark hereon and forward directly to commanding officer, Army Map Service.” The 1983 topographical map includes no such fine print, suggesting that the farther away one moves, the more accurate the surveillance.

Mirri Glasson-Darling’s “On Alaskan Literary Cartography” responds to a 1983 topographical map of Barrow Point, as produced by the United States Geological Survey. The imagery recorded in the map was captured by Multispectral Scanner System (MSS), a line-scanning device used to produce satellite imagery as part of NASA’s LandSat program. Previous topographical maps of Barrow Point, such as a 1950 version prepared by the Army Map Service, used aerial photography, a process that became increasingly popular during the years before and after World War II as it allowed the mapping of military zones without the need to step foot in them. Indeed, this corresponded with an increase in the military-flown imagery of Alaska and Hawai’i. Aerial photography was lauded for providing “a straightforward depiction of the physical and cultural landscape of an area at a given time,” although the 1950 map of Barrow Point included a note in its fine print that “users noting errors or omissions on this map are urged to mark hereon and forward directly to commanding officer, Army Map Service.” The 1983 topographical map includes no such fine print, suggesting that the farther away one moves, the more accurate the surveillance.

Caroline Goodwin’s “Field Samples” excerpts 16 poems from a larger series that respond to the flora found in the book Common Plants of Nunavat by Carolyn Mallory and Susan Graham Aiken, though the majority of the illustrations come from the eight-volume series Illustrated Flora of British Columbia, which are featured on UBC’s Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia. These various archives offer an unsurprising Venn diagram of data, the electronic atlas offering interactive maps and conservation information but omitting the First Nation plant names and uses Mallory and Aiken collected through interviews with Inuit elders, its dust jacket copy explains.

Caroline Goodwin’s “Field Samples” excerpts 16 poems from a larger series that respond to the flora found in the book Common Plants of Nunavat by Carolyn Mallory and Susan Graham Aiken, though the majority of the illustrations come from the eight-volume series Illustrated Flora of British Columbia, which are featured on UBC’s Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia. These various archives offer an unsurprising Venn diagram of data, the electronic atlas offering interactive maps and conservation information but omitting the First Nation plant names and uses Mallory and Aiken collected through interviews with Inuit elders, its dust jacket copy explains.

The preservation of native languages is a fraught project throughout the Americas, but especially so in Alaska, where, according to the Alaska Native Place Names Project, there are twenty distinct languages and various sociopolitical and logistical barriers that prevent a coordinated, sustained effort:

While there is a long history of place name research in Alaska...the resulting documentation is often inaccessible and in danger of being lost. Cultural sensitivities sometimes prevent broader sharing of place name documentation, and lack of secure data storage technologies prevent adequate archiving. Lack of coordination also results in duplication of effort. For example, at least four major place name documentation projects have been conducted independently in the Minto Flats region in the past few decades.

Sara Eliza Johnson’s “Top of the World” is a response to a 1955 USGS map of Utqiaġvik where it is listed as Barrow, a name cemented in 1901 with the opening of a post office and removed in 2016 after a citywide vote. The city is well-known in the lower 48 as a bit of trivia: North America’s northernmost city. Others will recognize the city from the comic 30 Days of Night, or more likely the 2007 Josh Hartnett movie of the same name, in which old world vampires reenact history by crossing the Bering land bridge during the polar night to drain the new world of its life’s blood. Though this was common in the mid-2000s, the movie was filmed on practically the opposite side of the world in New Zealand, which meant the Native Alaskan characters were cast with Maori and Pacific islanders actors. If IMDb trivia is to be believed, the ironies of the narrative and production were not lost on everyone affiliated with the project. The comic’s artist, Ben Templesmith, leaked the working title of the film: Crackers in Alaska.

Sara Eliza Johnson’s “Top of the World” is a response to a 1955 USGS map of Utqiaġvik where it is listed as Barrow, a name cemented in 1901 with the opening of a post office and removed in 2016 after a citywide vote. The city is well-known in the lower 48 as a bit of trivia: North America’s northernmost city. Others will recognize the city from the comic 30 Days of Night, or more likely the 2007 Josh Hartnett movie of the same name, in which old world vampires reenact history by crossing the Bering land bridge during the polar night to drain the new world of its life’s blood. Though this was common in the mid-2000s, the movie was filmed on practically the opposite side of the world in New Zealand, which meant the Native Alaskan characters were cast with Maori and Pacific islanders actors. If IMDb trivia is to be believed, the ironies of the narrative and production were not lost on everyone affiliated with the project. The comic’s artist, Ben Templesmith, leaked the working title of the film: Crackers in Alaska.

Meanwhile, back in Utqiaġvik, permafrost thaw is destroying civic infrastructure and unpredictable ice floes are forcing Inupiat bowhead hunters to abandon or adapt indigenous whaling techniques in favor of more modern, technocratic ones. Among these is a map the merges the old and new, overlaying “GPS trail locations with surveys of ice thickness” atop hand-drawn maps.

Joan Naviyuk Kane’s “Seven Poems from Dark Traffic” explore the gaps and errors of a 1731 map prepared by Joseph-Nicolas Delisle “for use in researching the lands and seas north of the South Sea.” Delisle, a French astronomer, constructed the map as part of his duties as geographer of the recently founded Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, which he’d been recruited to five years prior. Though primarily the academy’s astronomer, Delisle doubled as its geographer, practicing as a géographe du cabinet, meaning his maps were constructed not in the field but in his study, combining sketches, oral narratives, existing maps, and any other text that might represent a geography.

Joan Naviyuk Kane’s “Seven Poems from Dark Traffic” explore the gaps and errors of a 1731 map prepared by Joseph-Nicolas Delisle “for use in researching the lands and seas north of the South Sea.” Delisle, a French astronomer, constructed the map as part of his duties as geographer of the recently founded Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, which he’d been recruited to five years prior. Though primarily the academy’s astronomer, Delisle doubled as its geographer, practicing as a géographe du cabinet, meaning his maps were constructed not in the field but in his study, combining sketches, oral narratives, existing maps, and any other text that might represent a geography.

Tasked with producing a map to help Vitus Bering’s second expedition exploring whatever lay beyond the Kamchatka Peninsula, Delisle made use of a range of sources, including the testimony of the grandson of João da Gama, who claimed his grandfather spotted land while sailing from Macao to Acapulco. The land appears as an ambiguous coastline south and east of Port de Kamtchatka resolving the dominant feature of the map: a massive absence between Pays soumis a S.M.TE I. de toutes les Russie and Baye d’Hudson. Working from the assumption that “the author of the map would not have represented anything on uncertain ground,” Bering and his crew, which included Delisle’s brother, sailed in search of Gama Land only to encounter fog so thick it separated Bering’s ships, St. Paul and St. Peter, which both eventually spotted Alaska 300 miles and day apart after over two months of open sea. The return for both ships was grueling in different ways but exacted similar costs. Bering’s St. Peter was battered by a storm that forced them to beach the ship on an island off of Kamchatka where Bering and 28 others died, likely of scurvy. St. Paul managed to return to port in one piece, but six of its crewmembers, including Delisle’s brother, died of scurvy as well.

Despite the failures of the expedition, the men who managed to return did so with sea otter pelts that became the justification of decades of exploitation of the local Aleuts, who were forced to pay tribute to Russian traders (promyshlenniki) in the form of furs. When the threat of gunpoint failed, the traders would kidnap the wives and children of Aleut hunters, demanding extravagant quotas of pelts as ransom, forcing the hunters to leave for months during which time the traders made concubines of their wives. This abuse lasted two decades, not because of any advancement in ethics or diplomacy, but because populations had depleted, both the Aleut (slaughtered for rebelling) and otters (poached), after which the Russians continued south along the Alaskan coast.

Piper Lane’s “Spillionaires” maps the effect of the Exxon-Valdez oil spill on a fishing community. “A View of Snug Corner Cove” presents an image of Prince William Sound as depicted by John Webber, based on the account of John Hawkesworth who, like William Bligh, was a companion of Captain James Cook. The pen wash and grey sepia of Webber’s landscape is supposed to reflect the “miserable weather experience” of Prince William Sound. Because of the “very desolate and dreary experience,” Cook’s voyage did not expect to find any inhabitants though they were proved, of course, incorrect.

Piper Lane’s “Spillionaires” maps the effect of the Exxon-Valdez oil spill on a fishing community. “A View of Snug Corner Cove” presents an image of Prince William Sound as depicted by John Webber, based on the account of John Hawkesworth who, like William Bligh, was a companion of Captain James Cook. The pen wash and grey sepia of Webber’s landscape is supposed to reflect the “miserable weather experience” of Prince William Sound. Because of the “very desolate and dreary experience,” Cook’s voyage did not expect to find any inhabitants though they were proved, of course, incorrect.

Alexander Lumans’ “Three Tests” maps the recent history of Amchitka, an island in the Rat group of the larger Aleutian archipelago that was the site of three underground nuclear weapons tests:

Alexander Lumans’ “Three Tests” maps the recent history of Amchitka, an island in the Rat group of the larger Aleutian archipelago that was the site of three underground nuclear weapons tests:

- Longshot - conducted 1965; 80 kilotons; 2,297 ft. depth

- Milrow - conducted 1969; 1 megaton; 4,003 ft. depth

- Cannikin - conducted 1971; < 5 megatons; 5,873 ft. depth

As with other nuclear tests, those at Amchitka inspired noble but ineffectual protests that seemed to grow with the explosive yields of the tests. The response to Cannikin, to this day still the largest the underground nuclear test in history, was especially fervent, stoked by a 1969 article by Bob Hunter, a journalist for the Vancouver Sun, that raised concerns that tests could trigger devastating earthquakes and tsunamis in what was a seismically volatile region. After a demonstration at a US-Canada border crossing failed to deter the Milrow test, Hunter and a group of fellow “rainbow warriors” chartered an 80-foot herring and halibut fishing boat with the plan to sail to Amchitka. Though their boat never reached its physical destination—it was turned away by a US Coast Guard ship—it did have some impact as a “mind bomb” in the media war, contributing to a growing anti-nuclear sentiment and serving as the founding action of Greenpeace, adopted from the name given to the warriors’ fishing boat.

Despite these small, incremental victories The Supreme Court upheld the decision to carry out the test 4-3 and the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission chairman, James Schlesinger, equally aware of the power of image, brought his wife and two daughters to Amchitka for the Cannikin detonation to demonstrate the test’s safety, declaring “[i]t’s fun for the kids and my wife is delighted to get away from the house for awhile.” Daughter Emily was made available for soundbite, reporting the ground shook “like riding a train.” In many ways the entire test was a stunt. Amchitka was chosen for its ability to balance remoteness to American lives and proximity to Russian ones. Absent in this equation is the test site’s yet greater proximity to native Aleuts who—while driven away from this particular island in the 1880s by Russian fur trappers—were still close enough to produce blood and urine samples containing elevated levels of tritium and cesium-137 and to report increased rates of myelogenous leukemia and other radiation-linked cancers.

Rachel Mannheimer’s “Mars, Los Angeles, Cayuga Lake” is both an examination of different artworks and a reconsideration of the author’s Alaskan home. It is paired with a diagram of Robert Smithson’s 1969 “Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis),” which too is a reconsideration “of sculpture in relation to nature.” Despite his fame as a land artist, there is no evidence that Robert Smithson ever considered an installation in Alaska or, for that matter, traveled there, although there is a Robert S. Smithson of Anchorage, who either died in 2001 or 2014 and whose name can be found on an index of the “Fond Memories of Anchorage Pioneers.” “Size determines an object,” the author quotes Smithson, and that too might be said of the author’s relationship with her home.

Rachel Mannheimer’s “Mars, Los Angeles, Cayuga Lake” is both an examination of different artworks and a reconsideration of the author’s Alaskan home. It is paired with a diagram of Robert Smithson’s 1969 “Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis),” which too is a reconsideration “of sculpture in relation to nature.” Despite his fame as a land artist, there is no evidence that Robert Smithson ever considered an installation in Alaska or, for that matter, traveled there, although there is a Robert S. Smithson of Anchorage, who either died in 2001 or 2014 and whose name can be found on an index of the “Fond Memories of Anchorage Pioneers.” “Size determines an object,” the author quotes Smithson, and that too might be said of the author’s relationship with her home.

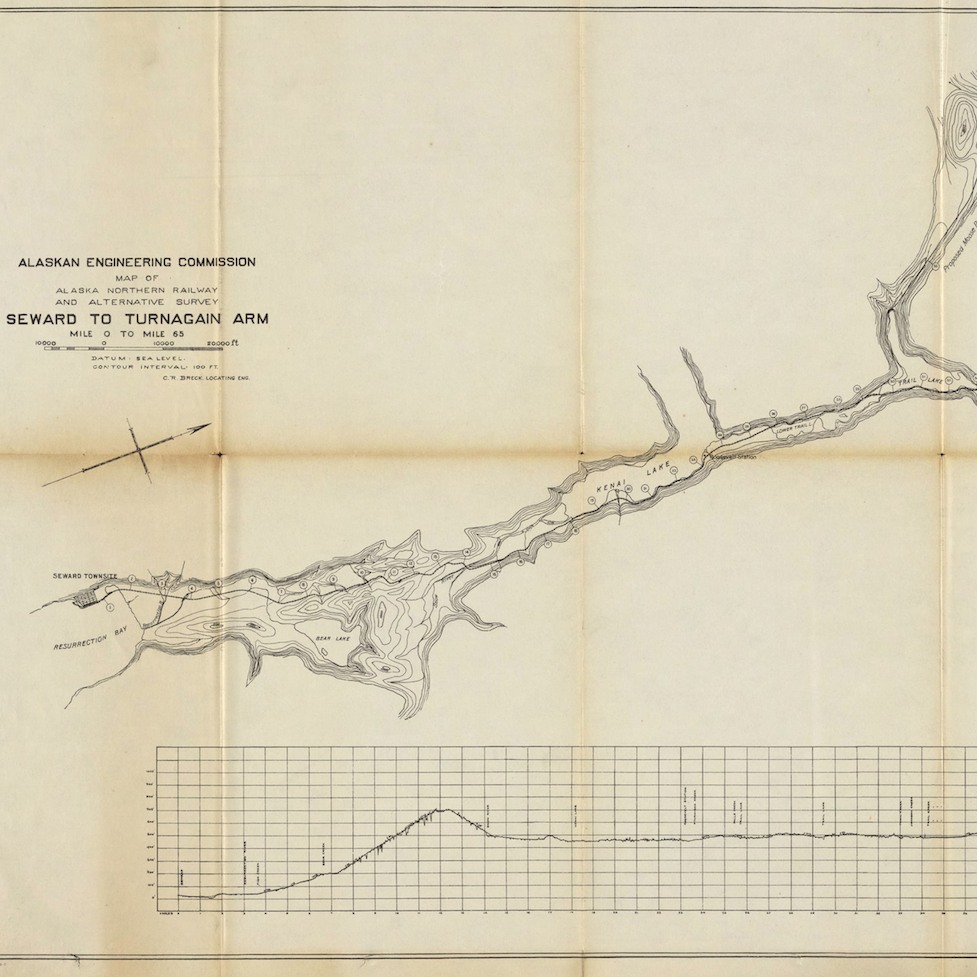

Kate Partridge’s “Brightness Values” responds to the Alaskan Engineering Company’s map of the Seward to Turnagain Arm of the Alaskan Northern Railway. Turnagain Arm was mistaken for a river by William Bligh, hence the name. Nine years after this mistake, Bligh would be bound and then set adrift with eighteen of his crewmen when the sailors on the HMS Bounty mutinied. Adaptations of the mutiny on the Bounty are a Hollywood favorite, with actors such as Charles Laughton and Anthony Hopkins taking on the role of the villain Bligh. Thirteen years after he starred in The Mutiny on the Bounty, Hopkins appeared as the lead in The Edge, a late 90s thriller set in the Alaskan wilderness, in which Hopkins has multiple run-ins with a Kodiak bear, played by the famed animal star Bart the Bear.

Kate Partridge’s “Brightness Values” responds to the Alaskan Engineering Company’s map of the Seward to Turnagain Arm of the Alaskan Northern Railway. Turnagain Arm was mistaken for a river by William Bligh, hence the name. Nine years after this mistake, Bligh would be bound and then set adrift with eighteen of his crewmen when the sailors on the HMS Bounty mutinied. Adaptations of the mutiny on the Bounty are a Hollywood favorite, with actors such as Charles Laughton and Anthony Hopkins taking on the role of the villain Bligh. Thirteen years after he starred in The Mutiny on the Bounty, Hopkins appeared as the lead in The Edge, a late 90s thriller set in the Alaskan wilderness, in which Hopkins has multiple run-ins with a Kodiak bear, played by the famed animal star Bart the Bear.

Contributors

In addition to the standard bio, we ask that our contributors share a location that represents them in some way. Collected together they comprise the genius loci of this issue.

Return to the issue cover page, preview upcoming issues, or learn more about how you can get involved.