I lack what is called a sense of direction. In my book Gymnasium, I included a photograph of a rice sack tied with a piece of string and dumped in some green undergrowth, which I captioned as Strange Fruit. It was a double exposure, the second image being a slightly enlarged version of the first. The idea was to give the impression of the nauseating stench that radiated out from the sack and also the withering heat in the air of the wasteland. I’ll now relate here the story of this sack. I used to walk the paths and scrub and dumps of this wasteland which borders The Flowers every day, and as a delineated space I knew it before and better than The Flowers. I still walk there often, I did so today, I still find it a therapeutic place to be, and it’s not much changed since the day when my wife first took me there to look at The Flowers. One day walking there I found the sack lying dumped beside a path that ran north from the frontal aspect of The Flowers and snaked back around to the main access artery through a zone I used to call the secret garden, a path to this day fringed with construction refuse and smashed fibreglass, a mud path full of divots and ruts and pot holes that would fill with rain water and reflect parts of The Flowers in a queerly dark pastoral way like a Constable painting under the sunset. I’d detected the odour of the sack some way before I arrived at the path’s turn off, and had slowed right down to hone in on it.

From the second that its perfume registered I knew it was a corpse. The throat-coating foul egg sweetness of a three-day-old. The smell is caused by bacteria in the gut that live on and start to eat their way through the dead cells of the intestines. This egg shit, surely the worst possible smell for a human being to endure, that is after the next stage of putrefaction (when the corpse turns black and begins to ferment), is most powerful at the point when the bacteria start to invade other parts of the swelling body — the thighs and other congealed organs in the chest — and green bruising spreads over the stomach. At this stage the body starts to kick out hydrogen sulphide and methane on top of the fruity meat punch and often weirdly strong stale piss and shit too, the remains of the intestines start to bulge and unfold their way out of the anus, and in this mocking way, the tongue sticks rudely out of the mouth, which can create some really memorable impressions. Horrible lung juice also seeps out of the mouth and nose, which smells like rusty iron mixed with the worst ever pasty fish bad breath you can imagine.

I scanned the ground and the rubbish excitedly. Wiry trees blackened with soot projected up out of banana-green foliage and sunken patchworks of crushed tiles. Further down the path dusty cattle began to drift across the artery into a different belt of scrub. One of them gave a long gravelly belch of warning, and then I saw the sack to my left, contained within a darkness of flies.

I hovered for a while in indecision, taking steps toward the horror and again retreating. The requirements were simply that I endure the stench, get through the flies which would go in my eyes and mouth, and open the sack, which I was growing rapidly afraid at the thought of. It was probably just more babes in there, but the dithering about and the ill discipline of my imagination had excited a kind of gothic naked city photograph of a hideous woman’s head with chopped up parts. Nasty detailed bits. A face I’d never forget that would look in on me when I tried to enjoy rare food, tried to come. Covering my face I picked up a stick from a pile of felled branches and tenderly poked the sack to gauge some impression of its contents, their weight and consistency. It was heavy with meat and no mistake. The smell was so egregiously corrupt that I began to choke.

Up the path rode one of the farmers toward me on a battered red two-stroke that I recognised, the handle of his long knife sticking up behind his shoulder and his face hidden in a khaki sun-mask. I know the man, but have never seen his face. He slows down and exclaims through his mask at the stench, and I gesture at the sack with my stick. It’s definitely a corpse I say. He dismounts in reluctant curiosity and we edge toward the thing together, both denouncing the odour, our voices eaten under the bombination of the flies and his idling engine. I let him take the stick from me into his gloved hand and he prods the sack as I had done. Some long and ambiguous seconds passed during which I was surprised I could notice the smell of alcohol through his mask. He was thinking and looking, hypnotised slightly by the sack’s riddle, and then he threw down the stick and cursed the smell again before nodding to me and grinning I think and getting back on his bike.

I returned the next day and the day after that. The contents graduated to its black putrefaction stage, indicated by the ripening of the stench into a hot sickly evil of yeasty meat with less egg and more rotten fruit and honestly, a slight tinge of garlic. The flies disappeared. I practised breathing this air. I tried to sit in front of the sack whose material has stiffened and become brittle in the heat. I took the photographs that I used in Gymnasium. Some time after this the smell wasn’t there anymore, and I knew that whatever was in the sack had dried out and its rate of decay slowed right down. Through a number of incidental factors the mystery also dried to some extent, its temptation, and the character it had given to the map through its intensity, and the sack became just another mundane visual landmark of waste matter that might disappear any day, like the medicine box pile, the suitcases, the beaten puppet, the eight bras hung from the bough of a tree, the charred metal skeleton of a reclining chair, the hanged bear, styrofoam city, or the remains of a certain specific rubbish pile today unexceptional — the precise spot where I saw a dumped abortion for the first time in my life.

The sack’s material cracked and degraded, and one day I realised it would simply disintegrate if I went once again at it with a stick. Inside were the almost dry black carcasses of four dogs moulded together into a big lump. A ripe knot of limbs and toothy snouts and ribs and leather with loose hairs lying on it directly beneath the crumbling fabric of the sack. I dropped the stick, took out my walkman earphones and rolled up my sleeves. I dropped to my knees and caressed the knot, exploring it tenderly with my fingers. It felt in turns like sticky hardened felt, uncured leather, old chicken bones, gummy liquorice. It unfurled tender little burps of odour. I was calm and agile with my fingers. I gently squeezed a gristled paw and tried to separate the toes, I ran my fingers over the exposed gums and teeth in a snout glued shut, I felt inside the eye sockets, poked my way between still flexible ribs and touched what felt like crumpled up pieces of slightly gooey cardboard. I lay both hands around the sides of the knot and tested its weight, which was still significant. I tried to release my hands and fingers through and about the knot without thinking about which part belonged to what, I tried to allow the information I brought with me to the knot to fall away behind the sensory material experience that the knot offered. I wasn’t successful in this, and I didn’t really expect to be. But both the intention and the effort were possessed of value and I knew it. Then I became more decisive with the knot. I bent and cracked open a snout and easily loosened some teeth. I roughly massaged the teeth and the ridges of the mouth’s roof with my thumbs, then pulled all the teeth out and sprinkled them on the ground. I separated one carcass out from the knot, twisted off its head and cracked the lower jaw right off. I tried to snap the rib cage in half but could not. I felt around in the cavities, and experienced a sudden rush of difficulty as I manipulated the genital area, which was not entirely devoid of features. I set to cracking and rubbing and pulling and scratching until I’d advanced my disassembly as far as was physically possible, within reason. I made myself sit for a further minute or so in front of my labour, which was quite possibly the most difficult part of the entire exercise, and then walked home with my hands carefully quarantined from the rest of me.

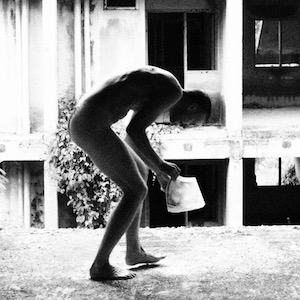

The few residential hovels located in the wasteland which are not connected with or a part of The Flowers — which is walled off and officially derelict — are occupied by local people. Refugees and immigrants like Burnt Penelope and her son, who find sanctuary and employment in this country, are normally concentrated into little shanty compounds made of bamboo poles and plywood and corrugated iron, which are built on or near their work sites and are disassembled as soon as the job is complete. Many of the villages in this district, which is only 10 kilos from the city, contain a little slum like this on a piece of unoccupied land or fallow paddy. I saw one of these burnt out once. Latched onto the wall of a monastic compound, the little kingdom was a brilliant vision in the light of the sun which reflected off the corrugated iron in dazzling white beams. Neat rows of hanging laundry and scrupulously tidy fireplaces in split tin drums. Deserted between 5am and 5pm, and then the same as any other village community at sunset — alive with recreation and eating and drinking and fires and children playing and singing. Men don’t come here alone, they come as family units, and the women and children work also, but for less money. The little kingdom was burning brightly after sundown, flames licking into the air, smoke billowing out from the doorways of metal rooms, pops and bangs and screams and cries, men and women corralling children and portering bales of laundry and whatever while some locals stood and watched. The community were moved one village over to open farmland, the kingdom built anew and identically to the former one beside the cement trail that stole through the paddy. I went many times to the burnt out site of the old slum to tread in the damp soot, to survey and occupy the space and to identify and appreciate relics, before the site was developed by its owner into a row of shophouses which remain unrented to this day. If you walk past the new slum just after the women who are to cook arrive back from the worksite, you are granted the vision of them bathing in the muddy water by the side of the iron wall in their sarongs. Compared to this, the commodious unbound vacancy of The Flowers allows Burnt Penelope and her son to enjoy what I would call almost unfathomable luxury.

We’ve been looking at a growing lump in her breast, which she is helpless to do anything about. Burnt Penelope’s status denies her access to doctors and hospitals. She is stoic but I know she’s worried about it because her eyes go out behind a forbidding concentration when we feel the lump together and dig around it with our searching fingers. I try to think of ways to use my own status to help, but there are none. What about the quack clinic that quietly does your son’s blood tests? Could they arrange something? I felt guilty right away because I knew this was an impotent suggestion. I just wanted to say something that indicated my concern and hastened a change of subject. I care and I think about it a lot but I can’t do anything.

I don’t mind your scars I said as I saw her fingering a tough thumb of tissue on her side. Why would you, she said. Some people might think they’re ugly or frightening I said, there are so many all over you. She stuck out her lower lip slightly in an expression of distracted bemusement. What’s this bit I asked. That’s where they poured hot water in my mouth. Boiling water? Felt like it. I fainted from pain and couldn’t swallow properly for a long time. Very hard to eat, especially anything solid. My teeth fell out. I wanted to die from the pain. Why did they do that? To torture me, she said. Why? Because they were soldiers she said.

There is a misunderstanding of the body that I work with. Skin is the only theatre. Nothing could be bleaker than the leaden mass of iron between the skin and the heart, or the empty distances that bracket facts where they are. From the very precise moment of death flies are attracted to corpses. Blowflies know and look for the stillness of corpses, so they can deposit eggs on the lips of wounds and orifices that hatch inside a day and pass through these open doors. A week later they have become maggots, another week still and they are new blowflies. And the flesh has only just started to break down. Burnt Penelope considers her life in The Flowers to be a paradise. She and I share this amazing notion for uncommonly different reasons.

At midnight an urgent breath of tropical wind rattled through the upper floors of the block I was lying in, rippling and fluttering through the structure’s bare doorways and windows and stairwells, summoning back to me with a jolt my little smeared position in the world and chilling the necklace of sweat on my neck. I thought of Penelope downstairs in her shack, inside which my clothes were thrown over a bamboo rail in the corner. The wind pressed again through The Flowers, the harmonics of this block airy and shrill, and the percussion of the rain began to play on the roofless concrete floor above me. Rainstorms here begin always with these gusts of wind and a sputtering overture by the rain before it then settles into a sustained and battering gallop. I enjoyed the noise, but the temperature dropped dramatically and I pulled my knees up to my chest with my arm under my head as a pillow. Rain water began to tumble through the windows and flow forcefully through pipe cut-offs and arbitrary holes and spaces and I was soon wet from head to naked toe and shivering. The entire floor beneath me was wet and the rain was now so hard that it had thrown off its percussive character and was like white noise, ferocious bales and blankets of water resounding off the layer of concrete above me, which was the floor of the top storey and rooflessly open to the sky, although the room also gave the impression of a subterranean cavern beneath a river system.

I raised myself and stood with my hands against the wall and urinated. I walked under the doorway into a horizontal spray of water from the open side of the building and used the exposed stairway to climb up to the top floor, moving carefully on all fours under the abuse of the rainstorm. I lay myself down in various attitudes, covering the sensitive parts of my body in turn as I let the rain pummel my flesh clean.

Less than an hour later the rain had slowed to drizzle but was still intoning in the floors below as it worked its way down across expanses of flat concrete and through the bottlenecks of the pipes and holes. The water then gave rise to a new cacophony in the form of croaking toads and frogs at once from every direction and none, as though released uniformly from the entire surface of the earth. Their clamour took on a faithfully human character, echoing up to me through the layers of empty rooms. I padded shivering back to the room from which I’d emerged and lay back down in the water. I thought again about getting to Penelope’s shack to dry myself and get warm and cuddle into her sanguine form, but I knew I wasn’t going. I slept where I was, cold but correct, in the anchorage of the salamander’s song.

I woke from my shallow rest extremely cold in the gathering light. The wet concrete had produced a ghastly affect on the parts of my body it had been holding — the kissed skin was wrinkled and clammy and without sensation. I felt a dire need to be warm, dry and clothed. I saw that the water had puddled only at my side of the room, and moved cautiously to the other side, where I urinated through a gap in the concrete that faced out onto the grassy foreground. I was able to watch the stream through the window above the gap as it emerged from the building and arched out through the air, breaking its linear crystal formation about two storeys down before disappearing forever. The weak bronze of the sun’s birth on the violet horizon reflected from this shimmering crystal spear in a beautifully exaggerated fashion through the gaseous atmosphere.

Then I climbed back up onto the top floor to enjoy the sky. I turned around and around, looking at the other blocks and the shape that they give The Flowers as a whole. The corner and the road and the wall against which Burnt Penelope’s shack was built looked to me from this elevated vantage like a secret valley basin in a mountainscape of reclaimed concrete. With my hands on the unfinished crenellation, which was so clean from the rain and so vivid in its spectrum of greys, to the heart of this secret valley world which was of course Penelope’s hovel, its corrugated roof glinting slightly like a new coin submerged in clear water, to the tiered tile roofs and towers of the organised world beyond (which formed a vague layer of referential space which in this light was disabused of its threat to us, its hegemony), and then sweeping out into the suggestion of nothing but the tarnished bronze sky with its violet wash — an abyss of light — before crashing silently into the dark mountains of the real horizon.

Is this a total picture of the world? I can taste the biscuit air and the breath of toads, I can smell the sweat from Penelope’s breasts. I look at the smooth worn concrete under my hand and tap my eyes a centimetre over the edge to plummet down toward the glinting roof of the hovel, whose contents, which include my clothes, I know and can picture right now, and then another slender tap over all the world except Penelope and I, which includes my wife and stepchildren and our vehicles and other possessions, and through the light to the dark velvet glamour of the mountain, upon which I have lived, upon which I have lost myself, upon whose violence and perplexities and endlessness I have spilt myself on and made love under. Despite the layers I have identified, this elevated vantage and the view it affords me is characterised by abrupt and dramatic variations in the distances between its components before it concludes in the halcyon and peaceful horizon, which like all horizons is a seductive projection of infinite youth, like the sea, and is like an ensign that we who wish to live well (Burnt Penelope and I) sail under. That mountain is a proven place, so to speak. My vision travels very far before it crashes it into its lines of credit. These abrupt and dramatic variations in distance between the milestones that measure my vision rip apart the so-called equality of matter, at least visually. And I believe the same applies in regard to other senses in which we can say that we see. I know it does. And I am.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

New Juche lives and works in upland Southeast Asia. He is the author of Wasteland, The Mollusc, Gymnasium, Mountainhead, The Spider’s House, Stupid Baby, and Bosun.

Rangoon

My heart — my centre — from which I measure all distances, is always in Rangoon, no matter the location of my body. Rangoon’s two centres – my hotel room and the actual centre – diverge gracefully from a central point along a sweeping arc, like an object dividing into twins as one forces one’s eyes toward each other. The actual centre, from which my hotel room slipped out, is the belly of the Queen, the womb of Queen Victoria.