“A more adequate definition of cartography needs to express not just the presence of geographical knowledge but also cosmographical or biographical information, such as the soul flight of shamans or the passage and pathways of gods, heroes, and ancestors.”*

We set out to make a map for our son, something to show him where he comes from, to explain the unlikely fact of his existence. We wondered: what could a map be?

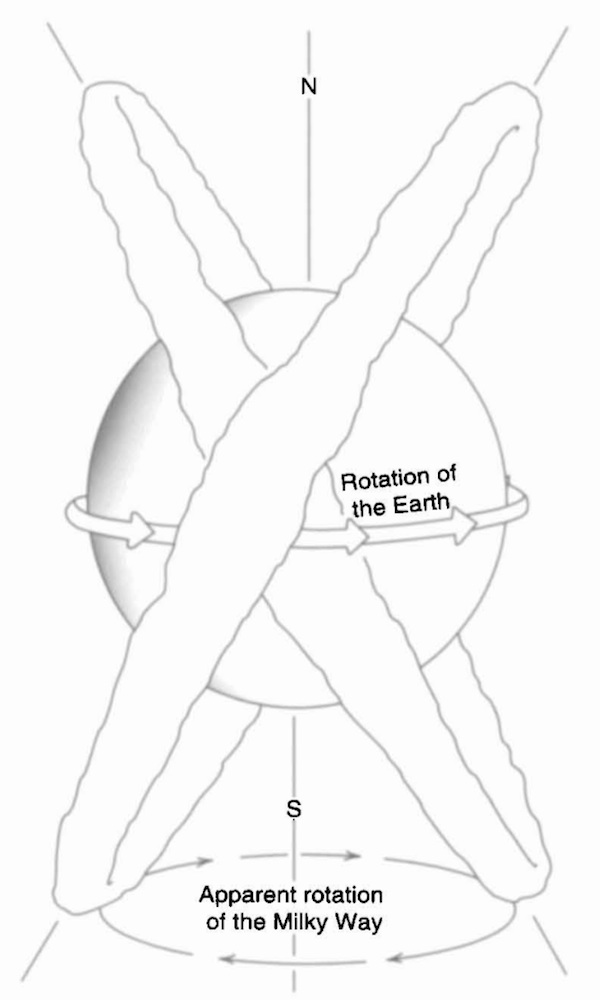

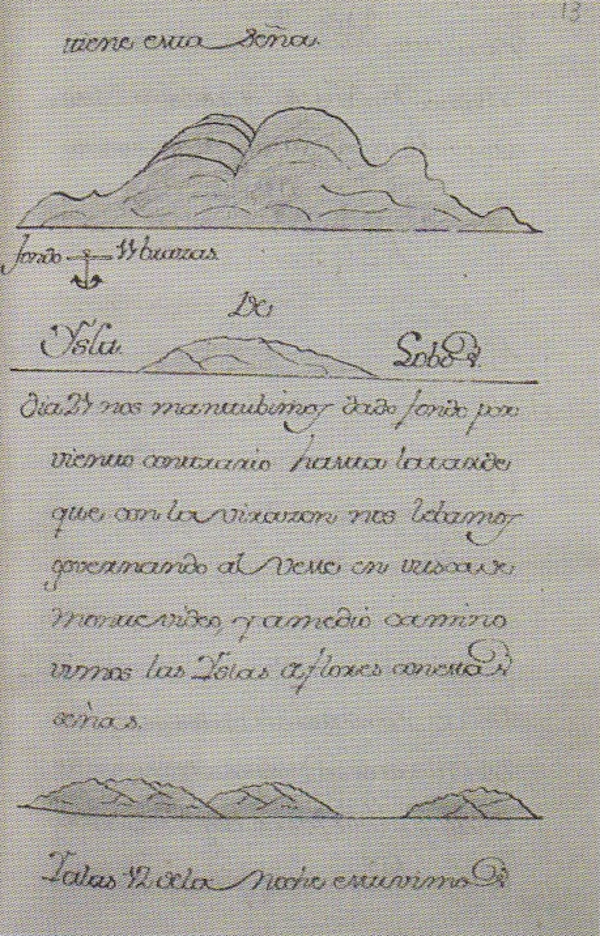

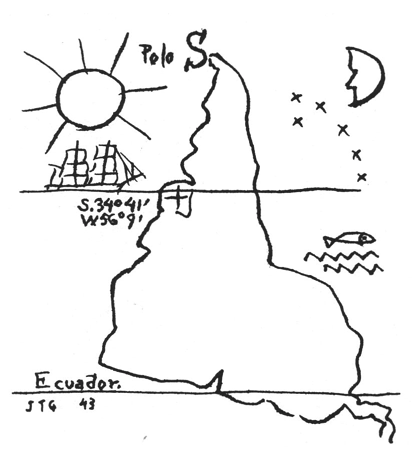

We weren’t starting from scratch — Jen’s a data visualization expert and Patricio’s a digital artist at a mapping company — but we wanted this map to reflect our son’s Argentinian heritage, and we realized we knew nothing about the history of maps in South America. Our research turned up a rich history of native South American mapping, combining earth and stars* with humans, plants, animals, and gods, into complex cosmographical systems*. We learned that daily and annual shifts of the Milky Way were used by the Quechua people to keep track of time*. We were inspired by the mass migrations of the Tupi-Guarani people, as they searched for guayupia*, The Land Without Evil. In addition to native maps, we found shoreline sketches from European navigators’ rutters*, drawn to help them recognize harbors that were new to them. We found the more recent south-up maps of artist Joaquin Torres-Garcia*, and the comic artist Quino*.

Our son’s genealogy is vastly more colonialist than native. He’s descended from kings and soldiers and factory workers and farmers who crossed the Atlantic, settling the Americas at the cost of native lives and freedoms. Hundreds of years later, we are still travelling to find success, now even more frantically: we move every year and change jobs every few years; each move taking us further from family and friends. Our comforts still depend on the lives of others less free than ourselves. In our families, the relentless search for guayupia goes back generations. Does seeing the futility and cost of the search mean we’ll call it off? (In our hearts, this is an open question.)

We set out to make a map for our son; we made it south up, to establish his geographic first principles in the hemisphere where his family lives; we include the earth and stars and shorelines, to help him find his way to the gods and heroes he’ll map for himself.

∅

Whitehead, Neil L. "Indigenous cartography in lowland South America and the Caribbean." The history of cartography 2.3 (1998): 301-26. p 303.

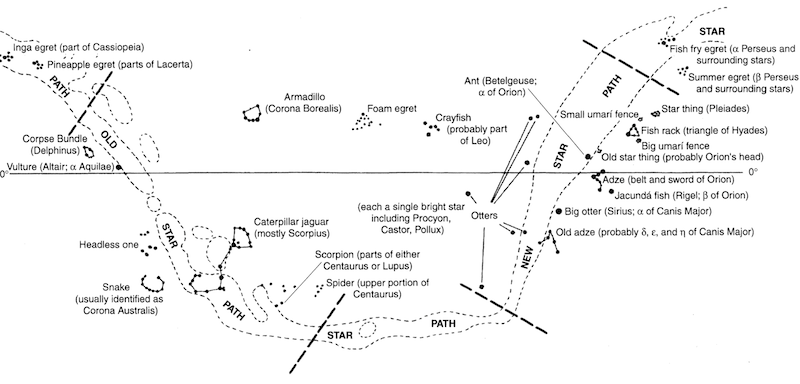

“The sky, both day and night, is perhaps the physical feature most constantly mapped by indigenous people... the relations between the people, animals, and plants on earth are often understood or represented by reference to celestial phenomena.” (Whitehead, 304)

Constellations of Barasana astronomers. (Whitehead, 306)

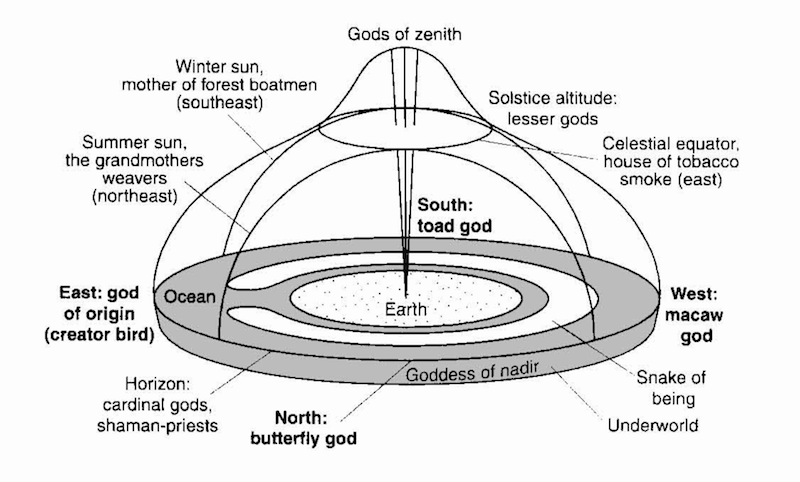

On their journeys across the sea the Warao could always remain at the center of the universe as the circle of the horizon traveled with them, and, if need be, they could establish a new home wherever two mountains could serve as the poles of their earth and the abode of the earth-gods. (Wilbert, 148)

Wilbert, Johannes. “Geography and Telluric Lore of the Orinico Delta.” Journal of Latin American Lore 5 (1979): 129-150

Profile of the Warao universe. (Whitehead, 315)

“...the search for places whose existence is indicated by cosmological ideas also forms an element of native cartography. The best-known example of this comes from the southern regions of South America and is part of the Tupi-Guarani cultural tradition. This is the spiritual and physical search for guayupia, the Land without Evil. This land of immortality and contentment was a product of the apocalyptic vision of the karai (prophet-shamans), and the hope of its discovery provoked mass migrations among the native people, who abandoned their villages and chiefs to follow the karai in their mystical quest. Such migrations had a uniformly east-west orientation and for some groups were directly identified with Kandire, the Inka empire toward the west. The arrival of the remnants of one of these millenarian migrations in Chachapoyas, Peru, in 1549, provoked an episode in Spanish mystical exploration, for the Spanish joined the Tupi in searching for the kingdom of Omagua, believing it to be El Dorado.” (Whitehead, 313)

Clastres, Helene. The Land-without-Evil: Tupi-Guarani Prophetism. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1995, p 22-24, 49-51.

Shore views typical of those found in navigators’ rutters.

Dym, Jordana & Offen, Karl. Mapping Latin America: A Cartographic Reader. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011, p 14.

Uruguayan artist Joaquin Torres-Garcia established The School of The South in 1934, known as El Taller Torres-Garcia (TTG). In 1935, he delivered an anti-colonial lecture announcing TTG, using this south-up map as visual rhetoric.

“Our geographical position, then, indicates our destiny. And we are responsible for it... we can do everything (now I’m referring to the vital things, those we could call telluric, that give the right aspect to everything); and then, not exchange what belongs to us for the foreign (which is unpardonable snobbery) but, on the contrary, convert the foreign into our own substance. Because I believe that the epoch of colonialism and importation is over (I am now referring to culture more than anything else)...”

Ramirez, Mari Carmen. El Taller Torres-García : the School of the South and its Legacy. Austin: Published for the Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, College of Fine Arts, the University of Texas at Austin by the University of Texas Press, 1992, p 55.

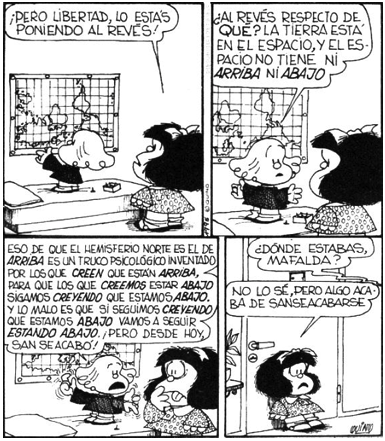

"But Libertad, don't you see. You are putting it upside down!"

"Upside down with respect to what? The earth is in space, and in space there is no UP or DOWN."

“That thing that the Northern hemisphere is UP is a psychological trick made up by those who believe that they are on TOP, so that those who think they are on the BOTTOM, keep beleiving we are DOWN. The worst is that if we keep thinking we are DOWN we will keep being DOWN. But from today this is over!"

"Where have you been Mafalda?" "I don't know, but from now on, this is it!"

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Patricio González Vivo (1982, Buenos Aires, Argentina) is an artist and developer based in New York and Buenos Aires. Patricio’s work has been shown at Eyeo, Resonate, Sundance, Tribeca, FILE, Espacio Fundación Telefónica, and FASE. He was a MediaLab resident at Centro Cultural Español. His work has been featured in Gizmodo, The Atlantic, and Fast Company. He's taught at Parsons The New School, NYU ITP, and SFPC (School for Poetic Computation).

Jen Lowe is a writer and researcher based in New York and Buenos Aires. Jen taught at NYU ITP and SVA's Design for Social Innovation program. She was a researcher at the Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia University, and she cofounded the School for Poetic Computation. She's spoken at SXSW and Eyeo, and contributed ideas at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Her work has been published in Scientific American and covered by The New York Times and Fast Company. Jen is also a member of deeplab, a collaborative group of women researchers, artists, writers, engineers, and cultural producers.

-1.182679, -84.764701

This is halfway between Jen's happy place on a mountain in Tucson, Arizona, and Patricio's happy place, eating milanesa on a patio in Buenos Aires.