Who hath measured the waters in the hollow of his hand, and meted out heaven with the span, and comprehended the dust of the earth in a measure, and weighed the mountains in scales, and the hills in a balance? (Isaiah 40:12)

I want to see the grave of a stranger. And so I leave a valley six hours north of Los Angeles to surf the fast flow of the Ventura Freeway and exit beside railroad tracks and the Golden Road brewery, passing Dinah’s Chicken, El Sauz Mexican Cafe, a street named for Chevy Chase, a billboard asking “Does God Exist?” I drive through the world’s largest wrought-iron gates and park at the side of Cathedral Drive, on softening asphalt in late July, in Glendale, ten miles north of downtown Los Angeles.

Forest Lawn Memorial Park lies before me, three hundred acres perfectly mowed. I stand at the steps of the mortuary, Tudor-style, a swooping brown-shingled roof dwarfed by surrounding green. A quarter million people have been buried at Forest Lawn in the century past, many of them Hollywood stars, artists, musicians. Beyond the mortuary, I see no grave markers on the rising swathes of turf, no dark monuments to endings, because the men who designed Forest Lawn found rows of headstones too grim for the climate of Southern California. The place seems to be an experiment in the virility of grass, a green blanket tossed over the earth, a picnic spot for giants, like no desert cemetery I have seen.

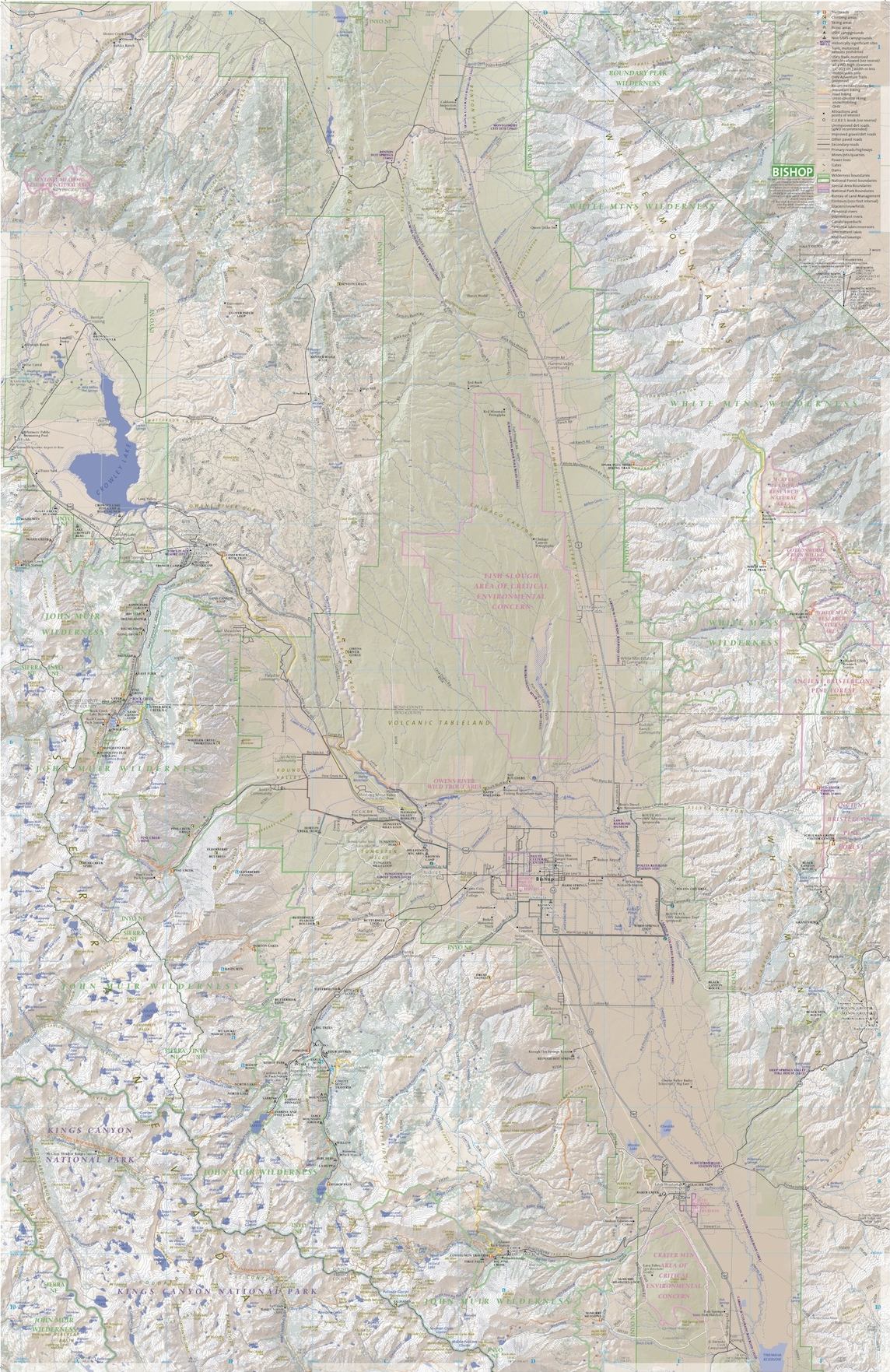

Two hundred and thirty miles north of Los Angeles, my father lives in the country he maps: a high desert valley called Owens, first dip in the Great Basin, at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada range. I was born in Owens Valley, and here my father sells maps. He carries a GPS on backcountry trails and sends data to a cartographer, then publishes the results and distributes them to local gas stations and visitor centers, who in turn sell them to tourists from Southern California. The tourists need direction. Their smartphones don’t always work in the mountains, and we hear tales of a family lost not far east in Death Valley, slouched without water in the shade of an SUV. My father makes a living from inked highways, streams, the wrinkled contours of mountains. He carries maps in the trunk of his car and he carries maps in his head. Ask him the names of the peaks—he knows. “Warren Bench,” he says, as I point. “Coyote Mountain.”

My father’s maps follow Highway 395 through the little towns of Owens Valley, four of them strung like beads, north to south, fifteen to thirty minutes apart—Bishop, Big Pine, Independence, Lone Pine. All but Independence has a small school with a few dozen students, a park, clustered gas stations and motels. “Welcome,” the banners on the streetlights read, “to the High Sierra.” Highway 395 becomes Main Street as it passes through each little downtown, the speed limit temporarily reduced to a friendly twenty-five. Beyond Main, residential blocks nudge into the desert. Then, sage.

Before my drive to Forest Lawn, I helped my father make his deliveries. We woke early and filled the back of his white Honda with bins spilling maps—Eastern Sierra Recreation, Yosemite Adventure, California Road Atlas. I counted bundles and snapped rubber bands. My father wore hiking boots and a frayed sun hat. He pinned his Sierra Maps name tag to the pocket of his blue button-up shirt.

In Bishop, we parked at the Chamber of Commerce. Inside, my father took a mental inventory: which racks stood empty, which titles did not sell well this summer. I waited in the passenger seat with the door open to dispel the heat, my shoes off, feet on the dashboard, and filled out invoices. “Bishop Region, thirty copies,” he called, grabbing bundles from the trunk. “California Road Atlas, twelve.” I wrote numbers next to titles and multiplied by corresponding costs. The invoices were photocopied and covered with handwritten notes. My father writes only in capital letters, with scant punctuation, but I have learned to make out his words. As he ran in and out, he left the trunk open. The sun fell on the bins, and I smelled chalky ink. I remember sitting in the garage as a child, pressing price tags onto covers with a sticker gun, the world smelling of maps.

Unfold one. Smooth the paper, waterproof and tear resistant, good for campers and hikers who submit themselves to the whims mountain weather—I have climbed a peak in July to find myself pelted by gum balls of hail and fled the summit amidst lightning.  A map must be strong. The color scheme is dust and sage. The shaded relief of mountains hems the valley east and west, elevations noted at twelve thousand, fourteen thousand feet. Highway 395 cuts a yellow line from top to bottom, paralleled by the blue wriggle of Owens River. Veins wind down from the mountains: Birch Creek, Elderberry, Coyote. All flow eventually into Owens River, a strip of water in a husk of brown.

A map must be strong. The color scheme is dust and sage. The shaded relief of mountains hems the valley east and west, elevations noted at twelve thousand, fourteen thousand feet. Highway 395 cuts a yellow line from top to bottom, paralleled by the blue wriggle of Owens River. Veins wind down from the mountains: Birch Creek, Elderberry, Coyote. All flow eventually into Owens River, a strip of water in a husk of brown.

Los Angeles swarms. To look from the parking lot of Forest Lawn to smog-dulled hills in the distance is to look at the soft body of a caterpillar quivering with ants. The very air vibrates with machine life. Cathedral Drive shimmers, and with uneasy gratitude I enter the mortuary lobby, where the air conditioning gusts cool and flower-scented, and the walls lull in pale stone. A few quiet men sit on benches, one staring ahead as if blind. Beyond the lobby, through open doors, I find the flower shop, and wonder whether I should purchase a lily. I am unsure how to approach the grave of the stranger I have come to see, but humility and devotion doesn’t seem like quite the right gesture. Perhaps an azalea, flower of abundance, or pink carnation, to acknowledge a debt. A daisy, for innocence? Or lavender, stubborn weed of drought-stricken yards—lavender, for distrust.

A woman with lined lips and bangs curled and shellacked waits behind the flower shop counter. Her name tag reads Iliana. She is maybe my age, a young woman at work for the common dead, for the wealthy and the famous and the very long in the ground. I ask her how I might learn the location of a grave. When I spell M.’s name, her face registers no recognition.

Beneath soft light I wait among the chilled mummies of orchids, dangling rosaries, kits for polishing bronze, while Iliana looks up M.’s grave in a back room. William Mulholland, at times called the father of Los Angeles, has become M. in my notes, the man who engineered an aqueduct that drained my home valley of water, that Los Angeles might grow. Those who got close enough in life to call M. anything called him solitary and hot-tempered. He had five children and a wife who died young from cancer. He loved the opera and photographed wildlife. He said, “Damn a man that doesn’t read books!” The workers who built the Los Angeles Aqueduct under his command between 1908 and 1913 sang in his presence. Some that witnessed his work stamped him a criminal and call him crooked still. Citizens of Los Angeles in 1913 loved him like a saint.

A grandmotherly lady stands behind me holding a bouquet of white roses, and I wonder if I ought to be ashamed, if I have no righteous purpose here, a tourist come to goggle at a monument to famous and ordinary death. And why do I come? Because I grew up calling a dead man bad. Because I came to live in the city he made when I had to leave home, as we all must leave our small towns for school and work, and learned to love something in the pink skies, the dirty waves tumbling shores. Can I love something and also wish it undone? But I do not wish to see Los Angeles undone. I could not tell the woman with the bouquet of white roses why I come.

M. was born in Ireland. His father blackened his eyes, and M. left home at fifteen, never finishing high school, to join the British Merchant Marine. He read about the town of Los Angeles, population seven thousand, then called Queen of the Cow Counties, germinating amid dust and chaparral, and arrived in California in 1877 to dig ditches, working sixty hour weeks to clear the city’s waterways. He earned three dollars a day, and with this money he bought seedling trees—eucalyptus, palm, willow, oak—which he tended in empty salmon tins. He lived in a wooden shack, kept cold in winter, where he lay on a bed I do not imagine as soft and read Shakespeare and manuals of engineering and hydraulics.

Mulholland worked in mud and dirty water until, near the start of the the twentieth century, he climbed to his apogee as superintendent and chief engineer of water works. The population of Los Angeles frothed to 100,000 and the city lost its saloon-brawl charm, its frontier austerity, and added a harbor, a public transit system, and a glut of white Midwestern Protestants, who looked round the desert and keened in remembrance of verdure. They demanded—from aquifers below their basin and the Los Angeles River, raging and receding at turns—twenty million gallons of water every day: 2.5 million to cut the dust of dirt streets, five million for lawns and gardens, and so on. In 1900, the mayor remarked, “If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the City of Angels must occupy a high place in the scale of municipal virtue.”

Responsible for bringing the bursting population more water than the Los Angeles Basin could provide, M. suggested to the city commissioner, half in jest, that the need for water might be checked by shooting the president of the chamber of commerce—the man responsible for advertising sunshine all over the country. But the president lived on; Midwestern newspapers touted the eternal summerland, and new Californians gushed west on the rails, planted gardens, turned on their taps to find only a trickle, and with pickets took to the streets to cry out for more.

“Repeat the spelling of the name?”

Iliana cannot find a record of the grave. I fumble—so many L’s—and glance to the grandmother. Sorry. I visit no dead husband, no stolen son. He’s a historical figure, I tell the cashier. No relation of mine.

“If he’s famous, his location might be private,” she says by rote. “We might not be able to tell you where he is.”

Strange to think of M. being anywhere, so still for so long—strange to think of a life landing like a stone tossed into the Pacific, a splash, a system of waves turned ripples, large and then small and then gone. He first saw my valley green with row crops, orchards, pastures. Over years he must have come to know it well—Main Street dusty and lined with hitching posts, and the Clark Hotel where ranchers came for ice cream—a land he lay brown, toppling cottonwoods in fine soil.

At the turn of the century, drought after brutal drought struck Los Angeles. “The time has come,” announced the water department, “when we shall have to supplement the supply from some other source.” In September of 1904, Mulholland and the mayor travelled north for two weeks by buckboard wagon. Were the river a snake, it might have hid among the willows of its banks. But the river is a river and it wound before the men, blue scales amid brown. An improbable river, said the writer Marc Reisner, in a true desert—a river that fixed Mulholland like a basilisk and turned him to a builder of empires.

At the turn of the century, drought after brutal drought struck Los Angeles. “The time has come,” announced the water department, “when we shall have to supplement the supply from some other source.” In September of 1904, Mulholland and the mayor travelled north for two weeks by buckboard wagon. Were the river a snake, it might have hid among the willows of its banks. But the river is a river and it wound before the men, blue scales amid brown. An improbable river, said the writer Marc Reisner, in a true desert—a river that fixed Mulholland like a basilisk and turned him to a builder of empires.

M. and the mayor of Los Angeles collected private information on land ownership and water rights in Owens Valley, and M. presented an engineering proposition that must have looked like a fever dream. Build a pipe 233 miles through the desert, over the Tehachapi Mountains? Yes, M. told the commissioners, the city people whose gardens shriveled in the sun. Yes! The mayor offered lavish sums for Owens Valley property attached to crucial water rights. Farmers believed they were selling water to a local irrigation project, and by late summer of 1905, the city owned sufficient rights to sustain the Los Angeles population, leaving a large surplus.

Legally, Los Angeles could only claim what it could use, and so the city absorbed a desert region just north called the San Fernando Valley. A bigger metropolis meant more debt could be taken on to complete the aqueduct, meant the city could collect more taxes, and provided more land for development. Plans for the aqueduct sent the new snake of steel, nine feet in diameter, through this annex to deposit excess water. A clandestine land syndicate formed, people whose support blazed essential if the aqueduct were to succeed, those Marc Reisner called the city’s “arch capitalists”: publisher of the Los Angeles Times, members of the board of water commissioners, railroad tycoons who held rights of way on the pipeline’s route. In 1905, no rain fell in June, July, or August, and on September seventh, citizens voted in support of the bond that built the aqueduct. By 1913, the project was complete.

This isn’t the whole story. The Forest Service played a part, as did the Bureau of Land Management, and President Theodore Roosevelt, and a writer named Mary Austin, who recognized a pattern that set her skin uneasy when land began to fly into the hands of city officials—who anticipated what might become of the Paiutes, first residents of the valley, reeling after years of systematic death by starvation, at rifle point, by the haphazard plans of the US Army—people already impoverished, indentured on the ranches that overtook their home.

Irrigation ditches require many hands to tend. Some of the ranchers of Owens Valley got a fair price from the city for land and water; many did not, and dynamite echoed in the valley now and again for seven years, and sections of pipeline lay flat after the blasts like a trampled serpent, and farmers dumped the tools of city workers into the river, and a crowd of seven hundred closed a set of floodgates leading into the aqueduct, turning the water back into the fields. Nearly four thousand laborers and many more mules performed their roles, and so did the citizens of Los Angeles who voted YES, and the newspaper headlines that cried out BONDS APPROVED BY MIGHTY WAVE OF ENTHUSIASM! SILVER TORRENT CROWNS THE CITY’S MIGHTY ACHIEVEMENT! FAITHFUL WATER SUPERINTENDENT WILD WITH JOY!

In the end, ranchers cannot ranch without water. The immense, saline lake south of Lone Pine, once the outlet for Owens River, dried in a decade, and when the wind blew strong across the lakebed, it tossed as much as seventy tons of dust into the sky in a second. Those who could afford to leave packed Model T’s and left.

Iliana returns with a Xeroxed map. Her fingernails click long, red as roses, shellacked. She’s highlighted a square on the white paper in the center of Forest Lawn. In private graves nearby lie the bones and ashes of the likes of Humphrey Bogart, Mary Pickford, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard. M.’s grave is public. He is not remembered in this city in a way that attracts ruin or worship, but he is remembered by me.

Before the gift shop, the trembling roses, the paper received like something at once precious and stained, I drove with my father and a cargo of maps through downtown Bishop, beneath peaks brushed white even in summer. Water, in these towns, constitutes the most notable export, and here folks are viscerally aware of its trail: falling as snow on the mountains, melting into tributaries, following an artificial course south. This river runs scarce and spoken for. Put your hands in the current and know that the water will journey far—through desert, then into a chemical bath, city pipes, and finally through storm drains and out to the sea. It passes between your fingers for a moment, but this water is swiftly moving on.

Owens Valley towns make a home for only certain people: those who have nowhere else to go, and those who will do anything to remain. In Bishop we passed Rusty’s Saloon, Rosie’s Psychic and Palm Reading, Dusty’s Pets. The stores stand boxy, running into one another; the horse-hitching posts are long gone, Main Street paved since 1924, but something of the old West lingers: dust, boots worn for work and not show. We passed Sierra Office Supply and the Sage to Summit climbing store, long-ago site of the Inyo County Bank, once a two story building with white siding and rows of windows. Pop’s metal map racks sit beside boxes of chap stick and key chains and postcards. He greeted the gruff men and women who stood behind the counters: leather-palmed fishermen, weekend mountaineers. They griped about the tourists who flood the highway in a train of headlights every weekend. “Tourons,” my father calls them, with affection. These people buy his maps: men with fishing licenses clipped to hats, women with tanning oil smeared over cheekbones. Some travel from Europe or San Francisco. Many swarm north from Southern California. They come to see the country, how remote, how bright the stars and vast the desert. They step out of cars, walk a hundred feet, and climb back in. They fear the bears in the mountains, the rattlesnakes in the brush, the yip of the coyote. The tourists, my father believes, their wallets flapping at hotels, restaurants, gas stations, gear stores, ski resorts, make it possible for us to live here at all.

I take the long way to M.’s grave, on foot. Back into heat, over grass roasting in a dry July. For all its posing as a park, no sidewalks line Cathedral Drive. You can walk over graves, markers flush with the lawn and running right up to the curb, or you can walk in the road with cars. These hills once lay “sere and brown,” an early Forest Lawn brochure informs us, until a San Francisco businessman took over the land and wrote his Builder’s Creed: “The cemeteries of today are wrong because they depict an end, not a beginning.” I pass no headstones; the dead of Forest Lawn embrace their beginning out of sight. How American, to herald death a glorious dawn, then hide it, and extol instead a lawn on life support, sprinklers perhaps more numerous than the deceased. Some designated day of the week, the place must erupt with a thousand riding mowers. Is this what M. wanted? A city that knows only beginnings grows forever.

Here lies a stretch of lawn dubbed Triumph and Faith, abreast of Ascension, Humanity, Harmony, and beyond that Immortality, Righteousness, Inspiration Slope, the Dawn of Tomorrow. Turn west to Victory, south to Summerland. It is all a summerland, this lull on a high place, surrounded by gauzy sky and hills dark with chaparral.

The Mystery of Life garden rests, green grass and white marble, an exultation of turf. Eighteen carved figures, some half-wrapped in robes, embrace and lament, gripped by ecstasy and despair—in this way like their countrymen, the living, who sleep and eat and walk beyond these grounds. The figures grasp and scold and raise arms to the sky, crammed together on an island of stone.

A group of tourists files into the Mystery of Life. They chatter and laugh out loud; I briefly despise them and then I remind myself that I, too, am a tourist. “This place is full of scenery!” A teenager says to his friend, as he lifts his phone to photograph the statues.

Forest Lawn is a chain establishment, this green sweep one of ten in Southern California. “I believe in a happy eternal life,” wrote the businessman, who named himself The Builder. And what did he build, but what he called a cemetery “as unlike other cemeteries as sunshine is unlike darkness, as eternal life is unlike death.”

Is all that I see hideous, or divine? It is fair to say Mulholland created a city unlike other cities, a city beneath eternal sunshine, diluted, slightly, as nitrogen dioxide mixes with atmospheric water vapor to produce a haze visible from the tops of mountains, which we call smog. In the city that surrounds, Mulholland may still be said to live. What he might make of his city, this extension of a mind that touched California briefly, I cannot say. A Mexican family passes by. The world is Spanish words and bird song, and for a moment I am unsure, as I am often unsure in Los Angeles, whether I am in chaos or at peace.

In Big Pine, ten miles south of Bishop on Owens Valley floor, ranchers once tended an immense canal called the Big Pine Ditch: a community project, every hand needed to rake away weeds and keep water flowing. Ranchers defended this ditch against city workers, but Big Pine rests sleepy now, the thrill of cocked rifles faded into dust and rabbit brush. The place where the ditch once shimmered lies an unremarkable compression in the earth. My father and I drove south toward Independence, where Mary Austin lived in 1903 in a little brown house beneath willows. Here, she wrote, “Treeless spaces uncramp the soul,” and I imagine her looking out the window at the Inyo range, the eastern valley wall. She must have walked in the desert and seen the granite rise of Winnedumah, the Paiute monument named for a man frozen forever in place, a spire silhouetted at dusk.

About seven hundred people live in Independence now. A Paiute reservation stands over the Army camp built in 1862 when white settlers decided they wanted the valley to themselves. Four white pillars mark the entrance to the courthouse, and the jail stands, a box of a building, the Sierra visible through chain-link and barbed wire.

The Eastern California Museum, on the corner of Grant and Center Street, tells the story of Independence. Water left and ranches fell worthless, even more worthless than the land in Big Pine and Bishop. Mulholland never turned his eyes to this town: the rights to the river he bought farther north, the water he re-routed around the farms. Like eighty-nine percent of private lands in Inyo County, the museum sits on soil still leased from Los Angeles.

Around me, green blazes like a dream, and I imagine the green in M.’s eyes as I draw him into immortality, these freeways, M., your limbs, police chopper and teenage boys drinking beer on beaches, waves washing trash, the Los Angeles River in its concrete bed. How hard it is to see the stars from the Griffith Observatory. I feel a traitor to valley people who carry the wound, to say: he would balk. For years of his life in Los Angeles M. lived in a plain wooden room. He enraged neighbors, installing meters on water pumps so they could not soak their lawns. In Los Angeles, he pictured theaters, quiet sidewalks. In the city M. knew, the fan palms wore shaggy skirts, and the sun shone. The streets ran wide and open; the sprawl hadn’t yet reached east to San Bernardino, north to Santa Barbara, south to San Diego. Belts of wetland and chaparral separated cities, and years passed before the San Gabriel Mountains slipped behind smog.

You die, M., and all that you made shudders around you. He resides among the blossoms of the beds he fed. This isn’t about us any longer, M. and me, my old hatred turning obsidian or melting like tar in the sun. This is wonder at what outlived him and will outlive me. We know not who picks up our tools when we lay them down. M. lost control of what he created, lost his vision, as sometimes happens when we deign to create or destroy, when a man hefts the weight of a river in his two hands.

Today the grass lives its green life only for me. A placard marks one native oak, somehow allowed to remain. From the bottom of a hill, I see white walls, a fortress, and now all that’s left is to climb.

In the southernmost town of Owens Valley, Lone Pine, alone in its swathe of desert, my sister and I played in the creek in Spainhower Park, across from an ice cream store that was always closed. I followed my father into Gardener’s True Value, High Sierra Outfitters, Joseph’s Bi-Rite Market. We drove on, and to our west we saw the Alabama Hills, brown orbs of monzogranite standing on end, piles of igneous rock clumped like crooked teeth, before the blue range. At our last stop, a Paiute teen worked the gas station counter. Even now the tribe wrestles Los Angeles and the federal government in court over water rights that the Paiutes never legally relinquished or sold.

I held the invoice on a clipboard, and she signed. Outside, the air was impossibly dry, stale-bread-in-five-minutes dry, and my father and I turned to drive the eighty miles back to Bishop. Out my window, the highway bent around seventy thousand acres of salt and mud flats. The pale crust of the lakebed stretches more than a hundred square miles.

When M. first saw Owens Lake, steamboats bobbed across the saline surface. The lake dried within thirteen years of the aqueduct’s completion. Once the natural end to Owens River, the bed blows a mineral fog. Scientists and city engineers converge here to try to knit dust to ground, but dust is not easily bound. As we drove, the dust flew high—a storm, a stampede of halite, mirabilite, arsenic.

The Colorado River Aqueduct of 1939 runs 242 miles from Parker Dam to LA. The California Aqueduct of 1997 runs over four hundred miles from the Sacramento Bay Delta to the farms of the Central Valley. The Catskill Aqueduct of 1915 carries water 163 miles to New York City. Its construction required the removal of three thousand dead from cemeteries.

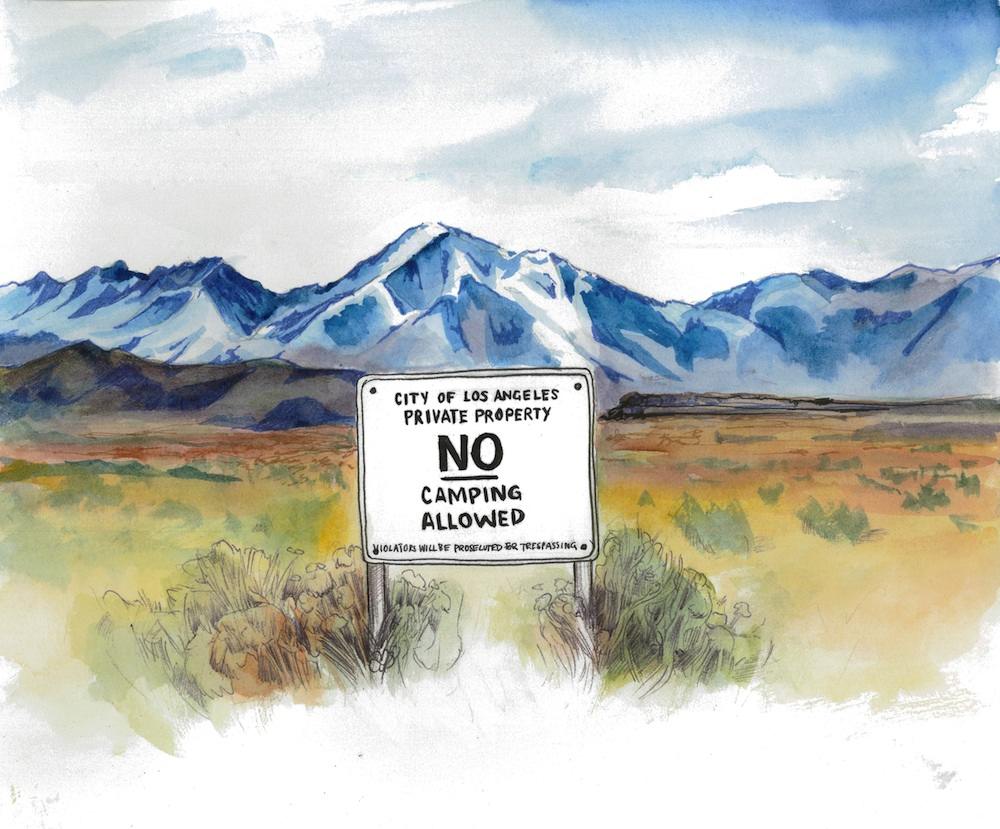

Builders of the Panama Canal came to California to learn from Mulholland’s work. The Los Angeles Aqueduct taught engineers the control they might exert over water, over land and the people already using land and water. Today, the city controls the terms of life in the valley, of environment and economy. In the desert, among clumps of brush and backlit by mountains, metal signs read CITY OF LOS ANGELES—PRIVATE PROPERTY—NO CAMPING—VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED. Owens Valley ranchers tend land leased from the city, and the terms of these leases are not always kind. Bishop businesses lease the dirt on which their stores stand. When I walk Main Street on a summer evening, do I walk the sidewalks of LA?

Builders of the Panama Canal came to California to learn from Mulholland’s work. The Los Angeles Aqueduct taught engineers the control they might exert over water, over land and the people already using land and water. Today, the city controls the terms of life in the valley, of environment and economy. In the desert, among clumps of brush and backlit by mountains, metal signs read CITY OF LOS ANGELES—PRIVATE PROPERTY—NO CAMPING—VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED. Owens Valley ranchers tend land leased from the city, and the terms of these leases are not always kind. Bishop businesses lease the dirt on which their stores stand. When I walk Main Street on a summer evening, do I walk the sidewalks of LA?

I have hiked the high country with a woman who once spent her days in meetings with officials from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, who felt herself emptied as ground slips away. Here and there a victory: the city must control the dust that billows from the lakebed, must return water to a portion of the river. In long drought now, the city takes one third of its water from the Owens, when it used to take two. But two steps forward sometimes turn to three steps back. Wells pump groundwater from beneath the valley for shipment south. The city announces the amount of water it plans to pump. The valley people object; scientists identify what will happen to local ecosystems if the city proceeds, and groundwater drops. “Dry soils blow away,” the woman tells me on the trail, amid split shade and the call of jays, the smell of sage and sap. “Entire meadow ecosystems blow away.” What remains? “Tumbleweeds, or—worse—nothing. In the short term, meadows gradually turn to floury moon-dust, and in the long term, ecosystems disappear.”

Driving with my father, I looked over salt flats and called up M.’s face: the sallow, mustached Irishman who, near the end of his life, stares past the camera in photographs. In a silent film documenting the pipeline’s construction, a middle-aged M. in a dark suit stands beside the river in Owens Valley. The camera captures his profile: weathered face, gray hair, bristling mustache. It may be a trick of the grainy footage, but his eyes appear hollow. He removes his hat, holds it at his back, glances at the camera. Then he walks out of the frame.

My father leaned away from the sun as it fell across his calloused hands on the steering wheel. It was late in the day. He glanced east, where the Inyo Mountains rose milky beyond the lakebed. The noise of our tires on the highway reverberated.

“It’s so dry out here,” he said, looking to the brown hills, looking at country that’s been his home for thirty-five years as if he’d never seen it. “Barren.”

The angle of the sun illuminated dust on the dashboard and papery bits of desert plants crept in through the window. I pulled cheatgrass seeds from my socks and pant legs. Cheatgrass is everywhere this summer, invasive, acres of thin stocks flattened in the wind.

“Los Angeles was just a big dry sunny place with ugly homes and no style, but good-hearted and peaceful,” muses a detective in a Raymond Chandler novel. Some historians believe that without a mind like Mulholland’s, the second largest city in America would today be a series of large towns—that without outside water, Los Angeles could not easily have grown beyond a population of 500,000. Smog might scarcely block the mountains, and Southern California might resemble, at least more closely, the place a geologist described in 1861. “Not less than ten or twelve thousand square miles were spread out in the field of vision,” he wrote of open land seen from the top of a peak southeast of the Los Angeles Basin. “Or, if we take the territory embraced within the extreme points—land and sea—more than twice that amount…the plain of Los Angeles and beyond, some eighty or ninety miles to the Sierra Santa Monica, with the Santa Clara Mountains much farther still, the tops covered with snow… We could see out on the Pacific a hundred miles from the coast.”

Had water, agriculture, and economic prosperity remained in Owens Valley, the tiny towns made up of people like my parents, in love with the proximity of wilderness, might now be a twin of Carson City, a Nevada neighbor with a population of fifty thousand and lights that compete with the stars.

I once imagined M. buried in a field so large it absorbs the sounds of the city, so that if I sat beside his headstone in the heat of July, eighty Julys after his death, the world could fall silent, a vacuum of time and consequence. In this absurd vision I walked across the field under a huge blue sky with a view of the sea.

It is not so hard now, from many places in Los Angeles, to forget about the ocean, and whatever else lies beyond your view, its length and limit set by the opacity of air. M. might have imagined a person like me, born in Owens Valley into a future he seeded, or perhaps he did not think into the distance so very far. Perhaps the future, to M., unfolded like the soft slopes of Forest Lawn.

We both knew the river and mountains and desert plains in centuries the other never saw. Perhaps we have not known the same place at all. If he did not, could not, think of me, why do I think of him? Why do I come looking for him in the hive of his creation, a city unlike any other, which I cannot dismiss? To what pressure did he bend, this installer of meters in neighbors’ gardens, and what did he begin?

In San Francisquito Canyon, just north of Los Angeles, a dam that held Owens Valley water broke a few minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928, releasing twelve billion gallons, a wall nearly fifteen stories high, that drowned or crushed more than 450 people, hours after Mulholland inspected and dismissed potential damage to the foundation. In trial, the beloved saint of the Angelenos said that he envied the dead.

To what extent must I live with responsibility to the places and the people I claim to love? Might the decisions of my life fan across an ocean, molecules bumping molecules into the haze of years, and are such concerns multiplied for those with great power? His stone drops into the sea and sinks beyond the reach of light. The uncounted dead of San Francisquito Canyon washed to the Pacific. The beach buffers ripples still.

I do not know why I pictured a grave with a view of the ocean. You can’t see the Pacific from Glendale anymore. And yet when I imagined the moments I would spend where M. lies I did not kneel in modern Los Angeles but somewhere surrounded by space, a place removed that allowed me to hold and consider all that he left, or at least to try.

At the top of the hill, at the end of Cathedral Drive, I stand in the grass and behold a fortress. In reality, M. lies in the Great Mausoleum, in a wing called the Sanctuary of Meditation, slot 6395. He sleeps in no open field, solitary and tranquil, but encased in stone at the heart of what he made. He isn’t far from Sunrise Slope, where tomorrow turns over and over.

Perhaps M’s slot is lavish and adorned, but I don’t have the chance to find out. The Great Mausoleum is closed. “Come back tomorrow starting at nine,” says the woman just locking heavy doors. But I do not want to find M. down dim halls. I know what I will see through the windows of the Mausoleum, can look now to hills a-thrum with so much motion you can’t clearly picture the horizon an instant after turning away.

The first gush of mountain water fell from the pipeline, hundreds of miles south of a fast-draining lake, on November fifth, 1913, in front of a crowd of forty thousand gathered to watch the floodgates open.

M. stood among them. He kept a vial of Owens River water until his death, and because of this I know the things he never forgot, even if I do not know what he was sorry for. Certainly he summoned California. This is his legacy. As for me, I turn and walk back the way I came. And I am sorry that I will not sit in the grass over his grave, and look up at the sky, as the city heaves around us.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Kendra Atleework was born and raised in the Eastern Sierra Nevada mountains of California. She's at work on a book that expands on her essay “Charade,” which appeared in The Best American Essays 2015.

Owens Valley Radio Observatory

At six years old I looked out the window of our house partway up the Sierra Nevada range and I could see enormous white seashells, forty miles distant and fixed to the valley floor. The Big Ears, we called them: satellite dishes that listen to outer space and gaze backwards to the birth of stars. Mountains stand at fourteen thousand feet on either side of the Owens Valley Radio Observatory and block interfering transmissions. For me, the Big Ears marked the borders of the known world. When I looked at those white beings made tiny by distance, I was certain that beyond them lay an elephant graveyard, a place of dangers where no one in my universe dared tread.