While picking through a grocery bag full of mesquite pods, sorting out the ones with black mold and chucking the few stray sticks, I talk to Brendan, a resident “Arconaut” and fellow pod-sorter. Probably only a few years removed from college, Brendan sports a grizzly lumberjack beard, flowy yoga pants, and aquamarine glasses; he’s rolled up his long-sleeved shirt, a constellation of well-worn little holes. He tells me his uncle used to be a welder here when they first built the site—in fact, he says, pointing to the giant circular window with asymmetrically intersecting supports, his uncle constructed these very frames.

We’re sitting in the café at Arcosanti—an experimental utopian community in the high desert, over an hour north of the Phoenix area. It’s the 3rd Annual Mesquite Pancake Breakfast sponsored by a bunch of people who wear cartoon slugs on their pins and T-shirts, whom I later learn are the Slow Foodies from Prescott.

Brendan has lived here in Arcosanti twice. Soon after he graduated college in North Carolina with a degree in sculpture, he took the Arcosanti workshop and petitioned for a residency. He stayed on a year or so, moved away for a while, and now he’s been back for a couple years. He lives in a private room with its own kitchen and bath, and he works forty hours a week as a bell caster, supplementing his income by creating sculpture, photography, and jewelry. He holds up his wrist to show me a silver ring and a dangly turquoise bracelet he’s made.  Paid minimum wage, he says it’s enough to support him. Brendan, like all the residents I’ve met, is easy-going and inquisitive. The slight hint of a North Carolina drawl seems to infuse his whole way of being, an unhurried and melodious undulation. Brendan ebbs and meanders around the room chatting with friends, grabbing a coffee, disappearing around a nook, and returning to sort more pods.

Paid minimum wage, he says it’s enough to support him. Brendan, like all the residents I’ve met, is easy-going and inquisitive. The slight hint of a North Carolina drawl seems to infuse his whole way of being, an unhurried and melodious undulation. Brendan ebbs and meanders around the room chatting with friends, grabbing a coffee, disappearing around a nook, and returning to sort more pods.

He tells me there’s currently 50 to 60 people who live on site, including volunteers and workshoppers. The atmosphere is transient; new residents arrive all the time, others depart. People stay for as long as they feel they need to, want to, then move on. The whole place has an ambiance of drift-ful bliss.

“Don’t get me wrong, there’s always issues that the community has to deal with,” Brendan remarks. “We can’t have really big blowout concerts anymore because our insurance went sky-high after the ‘car-b-que.’” He’s referring to the wildfire that spread to char or explode over 100 cars in the summer of 1978 during a music festival when a crowd of 15,000 gathered to see the laser show and headliners Stephen Stills and Todd Rundgren.

Arcosanti is run by the Cosanti Foundation, a nonprofit with a board in Scottsdale to handle logistics and budget, but the residents have an elected council on site, too. During the great recession five years ago, Brendan says, they had to shut down the agriculture department, which had become a money pit, mostly because the manager who took over didn’t know how to run it.  They’re trying to start it back up again. Another recent problem: the dam blew out during the monsoon season, and the run-off also uprooted some of their graywater system. They had just fixed the dam when the hail storms busted another hole in it a few days ago. These are the residents’ concerns—there’s no TV, and, although they have wifi, Brendan tells me there’s a distinct sense of being out of touch with the surrounding world, despite intermittent weekend trips to Flagstaff or Prescott.

They’re trying to start it back up again. Another recent problem: the dam blew out during the monsoon season, and the run-off also uprooted some of their graywater system. They had just fixed the dam when the hail storms busted another hole in it a few days ago. These are the residents’ concerns—there’s no TV, and, although they have wifi, Brendan tells me there’s a distinct sense of being out of touch with the surrounding world, despite intermittent weekend trips to Flagstaff or Prescott.

I ask him what he likes most about living here. “The communal aspect, working outside,” he says. “I have a great view every day. I have a place about two miles down the gorge where I make sculptures. And the smallness of the community—it’s tight-knit.” Cut off, laid back, drawn out: the day is abundant, there’s time to walk in every cast of light. To walk to the edge of one’s thoughts, down the canyon, where the river’s gushing right now, a brown curve glinting and foiled in the sun.  The hillsides lush with thorn and shrub, each verdant thing bright in the distance where a silhouette of a red-tailed hawk hovers and cauldrons.

The hillsides lush with thorn and shrub, each verdant thing bright in the distance where a silhouette of a red-tailed hawk hovers and cauldrons.

I, too, have the sense that the hectic pace of the outside world has been temporarily halted. It’s not only space but time that this architecture helps to shape, site as much as zeit. The downpour that has soaked the craggy lowlands, arroyos, and mesquite bosques since last night has abated. Clouds drift to the far horizon. The empty day floods with brightness. Late morning’s clear desert radiance streams in the skylight and huge porthole windows; looking down at the valley below, time seems protracted. It stretches, yawns, aerates, dissolves. The daylight slowly hums through the room. A solitary wisp of stratus levitates, stalled over a tabletop mesa in the motionless distance. The earth is a stark blade’s edge against the vibrancy of a translucent sky, a blue so deep it feels endless, the color when nothing is returned to the eye except the eye’s own aching sight.

Paolo Soleri, the architect behind Arcosanti, was a far-seeing futurist, a blinkered kook, or a charismatic charlatan, depending on who’s speaking. His ideas are as radical and revolutionary as they are, at times, grandiose and misguided.

Soon after obtaining his Ph.D. in architecture in his native Turin, Soleri worked under Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West in the late 40s until he was let go. Various myths abound, some claiming he was fired for incompetence, others banished by a jealous Wright who suspected his bright pupil might have been advancing beyond the master.  One apocryphal tale has it that Wright swooped in on his cape one day at a small residence Soleri and a friend designed. Wright poked around with his cane, claiming various architectural details as his own. Another tale has it that Mrs. Olgivanna Wright couldn’t stomach Soleri serving food (a fellowship at Taliesin involved menial labor) in his hand-stitched speedos, flip-flops, and grubby wife-beater.

One apocryphal tale has it that Wright swooped in on his cape one day at a small residence Soleri and a friend designed. Wright poked around with his cane, claiming various architectural details as his own. Another tale has it that Mrs. Olgivanna Wright couldn’t stomach Soleri serving food (a fellowship at Taliesin involved menial labor) in his hand-stitched speedos, flip-flops, and grubby wife-beater.

Soon after his dismissal, Soleri gathered some apprentices of his own to build his personal house near Scottsdale; next he was commissioned to design a ceramics factory in Italy, where he married his client’s daughter; then he started a ceramics casting-works at his residence, from which he later derived the idea of silt-cast architectural modelling. A mock-up of a bridge he conceived was displayed at MOMA in New York around this time, but what really put Soleri on the map was his book—filled with oversized blueprints and sketches—published in 1969 by MIT Press, Arcology: The City in the Image of Man.

His foundational concept of “arcology,” a neologism formed from architecture and ecology, purports that urban development must accord with the resources of the environment. Soleri was an early critic of the suburban sprawl that developed after Eisenhower’s Federal Highway Act of 1956, which abetted white flight, and not only left many cities blighted, but also left the natural landscape increasingly paved over. Soleri valued frugality, density, and ecological sanity, leading him to design more sustainable, multi-use habitats which reduced waste and pollution while maximizing human interaction and creative potential.

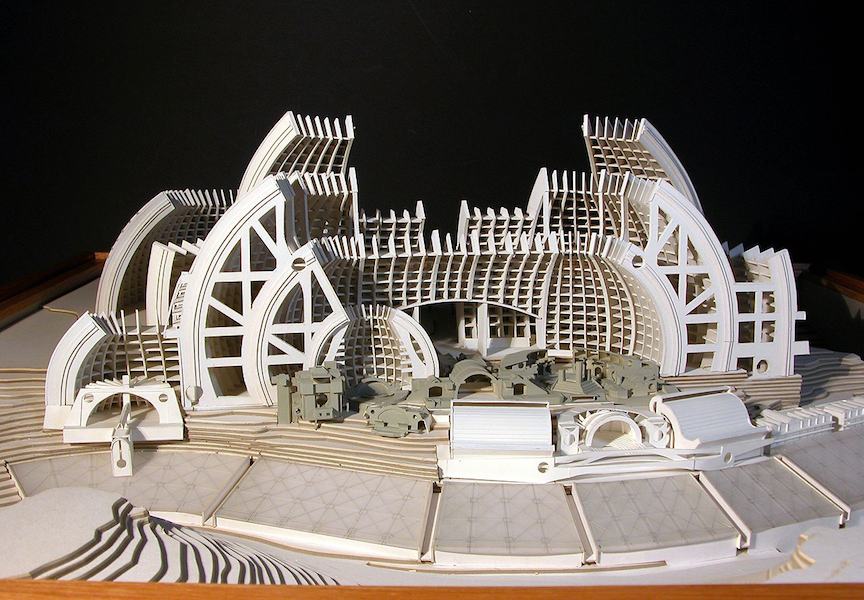

So far, so good. Sustainability is now a talking point of almost all new urban development, if not always a consistent principle of its practices. But it’s Soleri’s output—mostly in the form of books, manifestoes, sketches, diagrams, maps, and models—that leaves as many critics awestruck as it does scratching their heads. He is one of the foremost examples of the “paper architect,” on a level with such speculative draftsmen as Tatlin and Piranesi. His actual constructed designs, however, are limited to a couple private homes, the ceramics factory, his five-acre residence called Cosanti, a recently constructed bridge in Scottsdale finished in 2011—two years before his death—and the villa of Arcosanti, which is only 3-5% completed based on his blueprints and chipboards. The models for Arcosanti call for massive additional structures, some as high as 25 stories, which dwarf the existing buildings, leaving the present-day community in its shadows.

The model that sits in the visitor’s center display case shows the finished construction as a miniscule artichoke heart surrounded with the unfinished outer apses like bracts furling up in ever-taller thistles above it.  In the model, shown to the left, the tiny gray structures are the existing buildings; the white structures are the unfinished plans. Arcosanti—part humble eco-village, part Chautauqua, and part back-to-the-land commune today—was intended to be a functioning “urban laboratory” with a population of 5,000 to 7,000 inhabitants.

In the model, shown to the left, the tiny gray structures are the existing buildings; the white structures are the unfinished plans. Arcosanti—part humble eco-village, part Chautauqua, and part back-to-the-land commune today—was intended to be a functioning “urban laboratory” with a population of 5,000 to 7,000 inhabitants.

Even so, Arcosanti is one of Soleri’s more modest designs. His other proposals include city-sized structures such as Stonebow, an arch with a population of 200,000 over 300 acres, which would be suspended above a deep ravine much like the Grand Canyon; Mesa City, a system of toadstool-like structures built on a massive inclined plane so that each level would have a different climate zone; Nova Noah, a floating geometric megalopolis that would be as large as a borough of New York City; and Hexahedron, with a population density of 1,200 persons per acre, in the shape of two gargantuan pyramids conjoined at the base and supported on plinths. These megastructures are explicitly modeled on the more “sophisticated organisms,” such as bees and ants, which, Soleri asserts, create colonies with “optimal dimensions.” Needless to say, these projects and others remain on the drawing board.

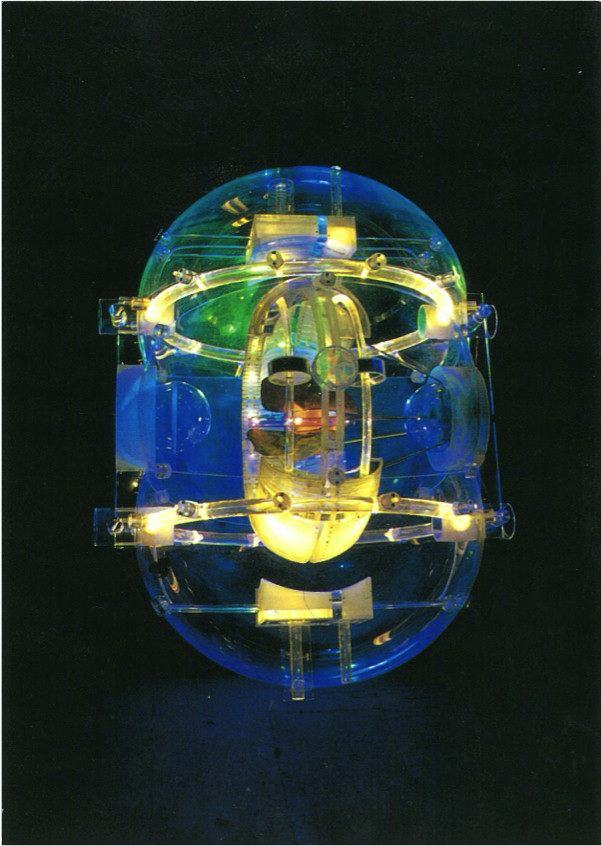

Upon returning home, I examine a postcard I purchased at the gift shop. Against a black backdrop that decontextualizes the image, the picture resembles a transparent jelly bean with a viscera of electric orbs and halos. Strange glowing green and blue clouds are trapped inside. It could be mistaken for a whizbang new Roomba, a lost prop from Jodorowski’s Dune, or a cybernetic brain that projects its own MRI scan. I flip the postcard over where it informs me it’s actually a model for another of Soleri’s cities, this one a space station encased around an asteroid. Somehow this doesn’t surprise me. When I was wandering around Arcosanti, I noticed an abstract sculpture on the wall, a trefoil of overlapping Reuleaux triangles. Titled “Airport,” the plaque underneath explained that it was a model for a flying saucer landing pad.

Upon returning home, I examine a postcard I purchased at the gift shop. Against a black backdrop that decontextualizes the image, the picture resembles a transparent jelly bean with a viscera of electric orbs and halos. Strange glowing green and blue clouds are trapped inside. It could be mistaken for a whizbang new Roomba, a lost prop from Jodorowski’s Dune, or a cybernetic brain that projects its own MRI scan. I flip the postcard over where it informs me it’s actually a model for another of Soleri’s cities, this one a space station encased around an asteroid. Somehow this doesn’t surprise me. When I was wandering around Arcosanti, I noticed an abstract sculpture on the wall, a trefoil of overlapping Reuleaux triangles. Titled “Airport,” the plaque underneath explained that it was a model for a flying saucer landing pad.

Soleri thought his buildings would impose their form on human culture, remaking the function of life in their own image and divorcing us from our dependency on reckless consumption. Among his many other pontifications, Soleri once took this premise so far as to state that human beings might evolve into the shape of cubes after living long enough in his arcologies. This is the kook part.

The charlatan part comes in when the salvific overtones of his gospel are leveraged to recruit young interns who pay for a five-week seminar that had consisted, for many years, of hard manual labor in the Arizona desert building the site. It doesn’t help matters, either, that the spaces offered to those taking the Arcosanti “workshops” are cubes, tents, or tin-roofed shacks the size of jail cells. Then again, Soleri was only learning from his mentor.

And yet, despite their elusiveness and hubris and impracticality and pretension and wingnut assumptions and sketchiness, Soleri’s far-ranging plans still possess an invigorating chutzpah. He remains one of those interdisciplinary public intellectuals that emerged from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s—like Chomsky, Goodman, or Foucault—who might just think big enough to have a chance of tackling the systemic problems faced by modern society. Perhaps we’re still too far behind Soleri’s prescient vision to fully appreciate the genius of his futurism. Perhaps there will be no future if we don’t catch up.

Because I didn’t get a chance to gather mesquite pods as planned, due to the early morning showers, Lana, an Arconaut, gives me a tour of the property. Lana is mid-twenty-something, put together in skinny black leggings and a keffiyah wrapped around her neck. Her eyes are hazel with flecks of moss and russet. A few wavy tendrils of hair that escape her perfectly messy bun complete her Coachella-ready look. Indeed, most people around Arcosanti feel more boho than hobo, sporting hipster designs rather than dirty hippy dreads.

The earth is mucky from the unprecedented nightlong rains. Mud clumps to our boots as we trudge to the canyon’s edge, around a makeshift compound of tents and RVs, old buses and military surplus vehicles, then past a grove of olive trees. Uncultivated succulents and blossoming prickly pear cacti poke up around us. Captured rainwater irrigates the fields and vineyards. We walk by the greenhouse that Lana has begun to revitalize, a solo project she’s recently taken on. This side of the complex holds a sculpture garden, too: large contortions of welded scrap metal waterfall, cowgirl, pas de deux, interlock, and helix.

Looking down the valley, Lana points out the mesquite bushes from which we would have gathered. The desert below is green, a capricious joyful freckled green, the whole valley a varicolored puckish swatch of it. The river rages, froths, and shines. The wash hasn’t run for many years, I’m told, but the monsoons have been particularly heavy this season. After-rain glistens on a few thin leaves.

Lana gestures to the powerlines that curve away toward the Bradshaw Mountains to the west—there’s a rockface with petroglyphs over there.  The Hopi used to signal each other across the valley, she says, and trap antelope down in the canyon.

The Hopi used to signal each other across the valley, she says, and trap antelope down in the canyon.

When we arrive back inside, breakfast is ready: eggplant frittatas, blue corn and mesquite pancakes, and ripe green Kadota figs harvested from the orchard.

Lana says she had been traveling all around the country for over a year before she came to Arcosanti. She stopped and fell for the place and now she’s been a resident for over six months. Growing up in a suburb of Dallas, she later became an elementary school teacher in Denver—her whole life had been spent in boring manicured American bedroom communities. But, burnt out from teaching, she became a groupie for a rock band—one she didn’t even like. She kept up her peripatetic habits until she took an Arcosanti workshop, then stayed on. She’s now studying woodworking. Initially learning tiling and dry wall, she’s recently graduated to cabinet-making.

Lana finished her first cabinet this week, which has been placed in one of the Airbnb “cubes” on the south side of the complex. The Airbnb helps supplement the foundation’s income, most of which derives from the workshops ($1500 for five weeks) and selling the bronze and ceramic cast wind-bells made in the foundry. On our visit, my partner met a retiree who rented a “cube.” He had just started the Ph.D. program in Sustainability at Prescott College, and he didn’t realize how far away the site was from—well, anything.  Prescott College is over an hour away. Still, the Airbnb brings in people from all over, many of whom have never heard of Arcosanti before.

Prescott College is over an hour away. Still, the Airbnb brings in people from all over, many of whom have never heard of Arcosanti before.

Lana says there’s often enough going on around Arcosanti that she doesn’t get bored. Over 60,000 visitors a year tour the facilities, especially during the fall and spring for the performance series. The international convention of stilt dancers has a weeklong festival of in situ performances come September, including stilt dancing dogs and fire-jugglers. Currently, a Shakespeare troupe is rehearsing Hamlet. Lana likes to escape about once a month, whether traveling just up the road to Sedona or for a longer getaway to Oregon. But for the time being, Lana’s wanderlust has subsided; she’s content to stay at home.

Cracks spiderweb through a few windows at Arcosanti. None of the windows are standard size or shape. They’re bisected circles, isosceles triangles, ellipses, ovoids, arches. Each one requires a custom design, making them time-consuming and costly to replace. Yet, the irregularity of the windows—and the splintering in some of them—disrupts one’s habitual indifference, what Heidegger called the “ready-to-hand.” In most encounters with traditional architecture, we only register the conventional use that something affords. Doorknob, light switch, wall socket. We occlude the physical properties of our surroundings into unacknowledged background.

But these windows draw attention to themselves; they stand out, forcing us to see them. Heidegger’s word for this phenomena is “breakdown,” and in this case it’s particularly apt. We not only register the window itself, and its cracks, but we also notice the landscape made newly visible beyond it. These odd windows defamiliarize us to our environment. We realize, with open eyes, that we’ve been blind all along. The light refracts, the frame coheres, and finally we look—the desert comes into focus, sedimented layers of ochre and rust, scintillated by sun, stippled with vegetation splintering up everywhere. Sharp, vivid, fecund.

In a society of unremitting quality control, the thing that most often suffers is quality of life. More and more of the world is becoming standardized, invisible. Urban theorist Keller Easterling, critiquing such homogeneity, describes how “microwaves bounce between billions of cell phones. Computers synchronize. Shipping containers stack, lock, and calibrate the global transportation and production of goods. Credit cards, all sized 0.76 mm, slip through the slots in cash machines anywhere in the world.” Multinational corporations have a vested interest in keeping us tuned out to these protocols. As Easterling observes, “contemporary infrastructure space is the secret weapon of the most powerful people in the world precisely because it orchestrates activities that can remain unstated but are nevertheless consequential.” Infrastructure space is designed to speed up the turnover of production and consumption: the faster money can be transferred, the more of it there is. Time is money; money is spatial. Our contemporary “generic cities” have been designed to be generic precisely to abet this zinging circuitry of goods and global cash-flow.

Human autonomy is lost in an ever-growing mise en abyme of infinitesimal measurements. With increased standardization comes less awareness. Roadside fast food chains repeat with numbing regularity. Suburban housing developments (and now whole cities) are slapped together as prefab modules. If you’ve seen one building, the show-home, you’ve seen them all. The internet is synched up through the very air we breathe—and we’re irate if the signal’s glitchy. As the world becomes background, becomes wallpaper, the bureaucrats who control such standards have greater power to expand their unseen empire of codes, platforms, zones, and jurisdictions.

Recently, I had an eight hour layover in Dubai. Arriving at the airport, I could whisk through security by having my face scanned and linked to my passport. My own biometrics integrated into the infrastructural calibration of commerce zones and transport systems, timetables and international regulations.

There was nothing to do, so my partner and I decided (what else?) to check out one of the malls. Passing through security, we hopped on the subway, exited the skywalk, wandered the corridors of the galleria, and found ourselves passing into a Sheraton. The spaces were indistinguishable. Dubai was all airport, subway, mall, food court, office towers, condos, and five-star hotels—one giant air conditioned concourse of haute couture shopping centers and fine dining divorced entirely from the shifting sands outside.  We ended up gawking through the glass at the skiing complex installed inside one wing of The Mall of the Emirates: seven-story bunny slopes and black diamonds, complete with ski lift, hot cocoa shack, snowmen, penguin statues, toboggan area, and an ice cave. This was the kitsch of a snowglobe writ large, self-contained, denying absolutely the habitat on the other side of its walls.

We ended up gawking through the glass at the skiing complex installed inside one wing of The Mall of the Emirates: seven-story bunny slopes and black diamonds, complete with ski lift, hot cocoa shack, snowmen, penguin statues, toboggan area, and an ice cave. This was the kitsch of a snowglobe writ large, self-contained, denying absolutely the habitat on the other side of its walls.

On the subway ride back, we shuttled past giant excavation sites, towering cranes. Chockablock against all this new development—museums, an opera house, high rises—several older condos and office buildings revealed cracks, boarded up windows, chips, and eroded façades. Their architectural style gave them away as built in the 80s or 90s. Already the slapdash construction methods had begun to disintegrate the first generation of skyscrapers, their materials unsuited to the gritty desert winds and humid Gulf air. These houses had been built on a foundation of sand.

The buildings at Arcosanti, some approaching 50 years old, also show signs of age: water-stains from leaky ceilings, hairline fissues in the concrete, faded paint, some jerry-rigged plywood paneling here and there at odd corners. To be honest, I had expected to see a geomorphic midcentury “machine for living” with all its Buck Rogers, space age accoutrements disheveled, decaying, and weatherworn; I imagined myself declaring that nothing wears out faster than yesterday’s vision of the future. And yet, almost because of the slight air of decay which pervades the structure, the whole villa seems renewed, as if these small indications of ruin were not, after all, harbingers of the place’s downfall, but, rather, evidence that the site is being lived in, used; that it is something primitive and brutal and imbricated in the seasonal cycles; that it is still malleable, evolving, organic, and alive. These architectural blemishes looked like wrinkles and cellulite, crow’s feet and liver spots; one might even say that they were beauty marks.

At the airport, on our return connection through Dubai, we zoomed through the concourse on escalators and moving walkways, then realized that after being cooped up in a plane for twelve hours, inside a pressurized cabin where we were wired to a thousand-channel TV, we should use the layover to move our legs and stretch our minds. Strolling the terminal, we contemplated whether we should visit the in-house pool or, suddenly feeling drowsy, pay forty dollars an hour to lock ourselves in a sleep-box. Instead, we slumped on sinusoid lounge chairs, our travel pillows abrading our necks, our carry-ons tied to our wrists. We had time to kill and yet we felt slowly killed by time.

At the airport, on our return connection through Dubai, we zoomed through the concourse on escalators and moving walkways, then realized that after being cooped up in a plane for twelve hours, inside a pressurized cabin where we were wired to a thousand-channel TV, we should use the layover to move our legs and stretch our minds. Strolling the terminal, we contemplated whether we should visit the in-house pool or, suddenly feeling drowsy, pay forty dollars an hour to lock ourselves in a sleep-box. Instead, we slumped on sinusoid lounge chairs, our travel pillows abrading our necks, our carry-ons tied to our wrists. We had time to kill and yet we felt slowly killed by time.

Day to day, whether in Dubai or Delaware, California or Katmandu, we experience a constant sense of delay, a postponement which accompanies the frenetic global lifestyle—an impatience at the impermeable thickness of temporality, the resistance of material, even of cyberspace itself with its bufferings and updates and downloads, wishing everything would go quicker, quicker, enough with waiting already, though of course each instant lasts as long as each instant dies.

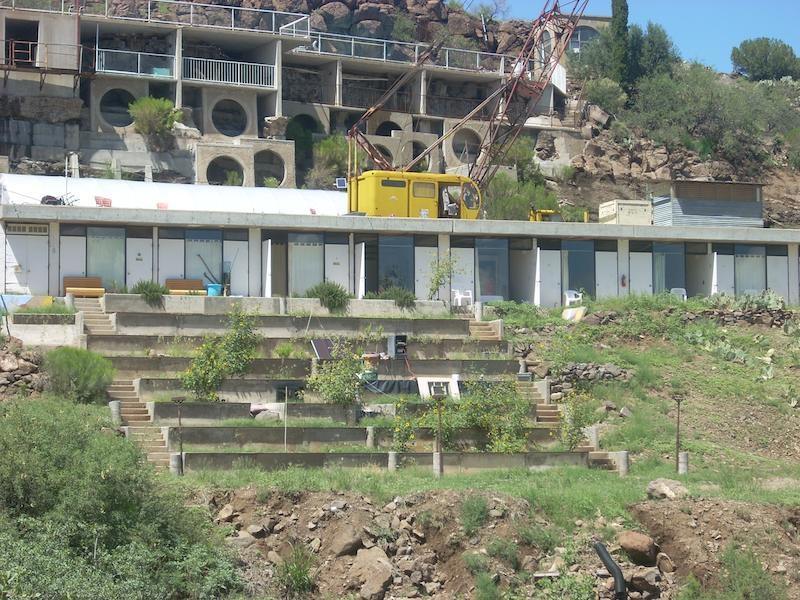

One of the first things Lance, our official tour guide, points out as we circle down the steps is how Arcosanti has been built right into the cliffside. Bare rock ledges project outward from the walls and into the stairwell. From the dirt road leading up to the site, I had mistaken the main villa for the outlying camp or the construction site known as “Plywood City” because the pictures of Arcosanti are invariably taken from a panoramic vista on the opposite side of the canyon.  Though the elaborate concrete towers and apses are up to five-stories in height—or, as it were, depth—they appear to barely protrude above ground level from the road.

Though the elaborate concrete towers and apses are up to five-stories in height—or, as it were, depth—they appear to barely protrude above ground level from the road.

Lance, in his early sixties, has shaggy gray hair and walks with a slight limp from a recent accident. He’s a former professor of Organization and Development whose latest position had been a visiting gig in Mexico. Before that, he lived in Nigeria and, he said, “other third world countries.” He confesses he still doesn’t know what an app is, and he’s just learned to text message a month ago. But he must have watched all The Lord of the Rings obsessively since he drops references from the movies throughout the tour.

The accommodations feel spacious and luxurious to Lance, who tells us that no two rooms in Arcosanti are alike. Residents keep switching rooms, upgrading based on their seniority, as other residents move out. Some areas have curvaceous, Gaudí-like rooflines that channel catchwater whereas others are windowless nooks, belated add-ons to the blueprint.  We pass by one residential space where everyone has hung up their laundry in the windows, one filled with Packers jerseys. A plastic pink flamingo perches on a stoop.

We pass by one residential space where everyone has hung up their laundry in the windows, one filled with Packers jerseys. A plastic pink flamingo perches on a stoop.

The furniture in all the common rooms is hodgepodge and hand-me-down. This is surprising since many modernist architects are famously control freaks. Mies, for instance, only allowed curtains in his Seagram Building to be closed in three positions. Gropius furnished his own house with chairs as boxy and severe as his own programmatic thinking. Philip Johnson’s Glass House had such an unlivable purity that he ended up residing in the nearby Brick House, originally designed as a guest suite. By contrast, the living areas at Arcosanti are comfortable jumbles of old love seats and mismatched barcaloungers, accented by a wild assortment of cow-skulls, seashells, and abstract posters. Lance informs us that Soleri, much like his architectural peers, was never too preoccupied with personal comfort. One time when he left for Italy, the residents, who had been agitating, simply built more studios without his permission. Soleri learned to live with it. Adaptation, after all, was one of his credos.

One older gentleman who tagged along on the tour was a longtime former resident, now retired to Prescott—he could recall some of the furniture had been used in the camp in the 70s. Nothing went to waste. In fact, the residents were currently looking to donate an extensive collection of VHS tapes, which had only been judged irredeemably outmoded in the past week.

In addition to its emphasis on re-use, the site has been designed with mixed and multi-use facilities in mind. Soleri broke from his mentor’s vision of a landscape transformed by ubiquitous automobiles. Wright, an early car aficionado, built his iconic Prairie Houses not for the windswept plains as architectural renderings often led Europeans to believe, but for places such as suburban Chicagoland.  Wright, in fact, has been credited with coining the term carport, an open air showcase for the vehicles he believed would mobilize every American and make conventional urbanism a thing of the past.

Wright, in fact, has been credited with coining the term carport, an open air showcase for the vehicles he believed would mobilize every American and make conventional urbanism a thing of the past.

Soleri, with a vehement disdain of the automobile and its byproduct of congested arteries and cloverleafs, was similar to urban planners such as Le Corbusier and Colin Rowe in that he favored ultra-dense, pedestrian-oriented cityscapes. He wanted to preserve access to parks or adjacent natural spaces. Much like Corbusier and Rowe, Soleri’s sketches segregate the urban layout into zones for residence, traffic, shipping, hotels, business, entertainment, and other functions. The failure of parsing out a city into such discrete zones, however, has been shown by Costa and Niemeyer’s Brasília—a monumental whitewashed capital, built to colonize the vast interior rain forest by a grid of hyper-rationalized superblocks each with its discrete bureaucratic purpose. Whole sectors of the city blackout at night, confining residents to their isolated plots; the vast plazas and surrounding vacant towers sweep upwards like mausoleums in an oversized cemetery.

But just as Brasília quickly became a swelling metropolis with its share of slums and urban congestion, sprawling outward beyond its planners’ original projections, Soleri seems to have reconsidered his early schematics. Adaption was his mantra. His philosophy took on the problem of designing not only built environments but total ways of life. The two went hand in hand. He asserted, “the American dream needs to be revised… If we begin to export that dream, it will offer disaster for the whole planet.” Instead of the disastrous fantasy of the burbs, which increases the remoteness between downtown workplaces and cul-de-sac developments, Soleri wanted to integrate labor and play, entertainment, culture, and community. He promulgated an ever-fluid reimagining of the human condition in which the built environment evolves alongside the changing capacities of ecological becoming: “space interpreting space interpreting space.”

On a modest scale, Arcosanti puts this idea in practice. The apses and exedras of the ceramics and bronze foundries are easily converted into bandshells and stadia for traveling performance troupes. The café can double as a communal space. The outdoor theater has a sunken network of moats that help cool off the surrounding residences. The greenroom is used as a piano and TV lounge when shows are not rehearsing. Evolution is on-going. When Arcosanti was built, extensive solar panels could power little more than a single dishwasher; wind energy prototypes were found to disrupt bird migration patterns. With advances in design, current residents are working on ways to incorporate wind and solar energy along with other improved technologies into the complex.

On a modest scale, Arcosanti puts this idea in practice. The apses and exedras of the ceramics and bronze foundries are easily converted into bandshells and stadia for traveling performance troupes. The café can double as a communal space. The outdoor theater has a sunken network of moats that help cool off the surrounding residences. The greenroom is used as a piano and TV lounge when shows are not rehearsing. Evolution is on-going. When Arcosanti was built, extensive solar panels could power little more than a single dishwasher; wind energy prototypes were found to disrupt bird migration patterns. With advances in design, current residents are working on ways to incorporate wind and solar energy along with other improved technologies into the complex.

One notable feature that had been key from the beginning is the lack of air conditioning. The whole site has been designed to regulate temperature through the use of circulating air by fans, swamp coolers, and vents; centralized flues push cooler air down to the common areas and openings allow heat to escape. South-facing windows and a passive heating system maximize solar gain in the winters. The bell casters noted that the foundry exhaust is piped inside during the winter, too, though their outdoor work stations are “outrageously, unbearably hot in summer.”

A Girl Scout troop is on the tour with us, and one girl whispers to her friend, who raises her hand to ask how many people have died in the foundry. The bell caster, chagrined, says that nobody has died while working, but that one person had died in the foundry several years ago. Lance later tells us that residents are looking to have a part time nurse on-site, though he notes the ambulance from Cordes Junction arrives in about ten-twelve minutes. A handful of the original members of the community from the 70s still reside here; they are getting on in age. Most have moved from the more spacious apartments at the top of the complex to ones where they have less stairs to climb in studios now dubbed “geriatric row.”

Although Arcosanti houses a few families with children, who either bus an hour to the local school district or are home schooled, most residents appear single and childless, nomads and idealists who don’t have to worry about daycare centers or nursing homes, afterschool programs or hospital facilities. The nuclear family has been largely abolished. What still gives Arcosanti its utopic feel today depends as much on Soleri’s genius for grand unified thinking as it does on how it resists Soleri’s space age pretensions, and instead maintains itself as a shabby, small-scale pastoral commune for new age hippies, artists, foodies, eco-conscious free thinkers, and other fellow-travelers.

In one of Italo Calvino’s invisible cities, “No one remembers what need or command or desire drove Zenobia’s founders to give their city this form, and so there is no telling whether it was satisfied by the city as we see it today, which has perhaps grown through successive superimpositions from the first, now undecipherable plan. But what is certain is that if you ask an inhabitant of Zenobia to describe his vision of a happy life, it is always a city like Zenobia that he imagines, with its pilings and its suspended stairways, a Zenobia perhaps quiet different… but always derived by combining elements of that first model.”  Arcosanti, like Zenobia, has undergone permutations that sometimes make its founder’s plan seem esoteric. Yet, the actual city is always a palimpsest, underwritten by shortcuts and “cracks in the panoptic gaze,” in the words of de Certeau, a groundwork that’s forever shifting and repurposed for the community’s over-riding needs.

Arcosanti, like Zenobia, has undergone permutations that sometimes make its founder’s plan seem esoteric. Yet, the actual city is always a palimpsest, underwritten by shortcuts and “cracks in the panoptic gaze,” in the words of de Certeau, a groundwork that’s forever shifting and repurposed for the community’s over-riding needs.

After the official tour, my partner and I go on a hike down the mesa, fording the river, and hopping along a muddy path out to the dam. A continuous stream rushes from the manmade pond into two twelve-foot deep fissures that have burst through the built-up mound of earth that’s the dike wall. I look upward at the villa on the hillside. Past the giant crane and cypress trees, Arcosanti comes into focus. It strikes me that the architecture appears like land art from the 70s. The buildings are an interpolation into the site's geomorphology, which sharpens our appreciation for the stark indifference of the surrounding desert even as those surroundings reshape the work itself. From my vantage down in the floodplain, the cast-concrete structure glints away into the afternoon sun.

Coming back up the hill, past the ramshackle encampment for newbies, we pass a sign that reads, “Arcosanti: Urban Laboratory?” The question mark betokens both failure and possibility. Neither exactly urban nor scientific, the community abides under the aegis of the interrogative and optative moods. The sign declares that the evolution of this site remains an open question, a provocation, a testament that this experiment is unfinished, a proving ground rather than a proof. Arcosanti seems a genuine experiment, neither a holographic bubble nor a specimen under museum glass. It’s a part of a larger habitat, living and dying, breathing the air and weathering the changes.

Leaving, I notice several nests that have been constructed in the crevices along the roofline from both swallows and wasps. During my day here I spotted a giant desert centipede, a rustic sphinx moth, and an iridescent green jewel-beetle. Everywhere, the grounds were tessellated with burrows, honeycombs, webs, and hives. On the hall to the bathroom on the way out, a tarantula hunkers in an inexplicable cutaway niche as if it were a household god nestled in its lararium or garbhagriha. It likely fled its burrow during the rains and appropriated the shelter of this convenient recess. Nature has begun to take the structure back over, a participant in its evolving design, as if the organisms such as ants and bees that Soleri envisioned as his models have inverted the architectural process to recolonize his space. Like the human inhabitants, these creatures repurpose the cracks and make use of the spandrels, recombining the elements of Soleri’s first model, adapting a space for their days.

Leaving, I notice several nests that have been constructed in the crevices along the roofline from both swallows and wasps. During my day here I spotted a giant desert centipede, a rustic sphinx moth, and an iridescent green jewel-beetle. Everywhere, the grounds were tessellated with burrows, honeycombs, webs, and hives. On the hall to the bathroom on the way out, a tarantula hunkers in an inexplicable cutaway niche as if it were a household god nestled in its lararium or garbhagriha. It likely fled its burrow during the rains and appropriated the shelter of this convenient recess. Nature has begun to take the structure back over, a participant in its evolving design, as if the organisms such as ants and bees that Soleri envisioned as his models have inverted the architectural process to recolonize his space. Like the human inhabitants, these creatures repurpose the cracks and make use of the spandrels, recombining the elements of Soleri’s first model, adapting a space for their days.

By late afternoon, driving away down the dusty access road past still-trickling arroyos and a truck depot, I head back up I-17, by the chaparral of the Verde Valley and the nearby ancestral Puebloan cliff-dwellings, the sandstone bluffs of Sedona and the rolling fields full of ox-eye daisies as the elevation climbs toward the snowcapped San Francisco Peaks, to Flagstaff where, at age 37, I’ve just moved into the fishbowl of a freshman dorm right in the center of campus, an artificially planned community if there ever was one. But that, as they say, is a different story.

For more information about this piece, see this issue's legend.

Will Cordeiro has new work appearing or forthcoming in The Boiler, DIAGRAM, Painted Bride Quarterly, Museum of Americana, Whiskey Island, and elsewhere. He received his MFA and Ph.D. from Cornell University. He lives in Flagstaff, where he is a faculty member in the Honors Program at Northern Arizona University.

(Latitude 32.234634, Longitude -110.947946)

1600 E. First Street

The University of Arizona

Tucson, AZ 85719

One summer my best friend and I road-tripped from Brooklyn. In Tucson, my first time there, we checked out the Poetry Center—the old facility on Cherry and First. The place was shuttered for the move to the new building. We got in the door somehow, but never as much as sniffed a single line. An undergrad, packing boxes, told us we had to leave. We skulked away. That intern, years later after we met again in grad school, is now my partner. So, books or no books, who’s to say what you’ll find at the Poetry Center?